To start, an apology. Sunderland AFC released their accounts for the 2020/21 season over two weeks ago now, and a breakdown of those accounts still isn’t forthcoming here.

The delay in publishing owes to a few things, though not least the feeling that, by the time further relevant information had been released, the focus was decidedly on two rather large games with Sheffield Wednesday. With a slightly sizeable tussle with Wycombe Wanderers on the horizon, we’ve decided the same logic applies – better to look forward for now.

With that in mind, a full look at the club’s recent accounts and, in particular, where the club and its owners stand, should follow once this season ends. If you’re wanting some insight on them now, a fair amount was covered in a Twitter thread on the day the accounts were published.

Alternatively, for reasons unbeknown to us, Newcastle United’s True Faith fanzine published their own piece on Sunderland’s finances over the weekend which lifted, almost word-for-word, large chunks of that same thread (but, of course, left out any real context or positive observations). If that’s more your bag, feel free to go read their piece written by David O’Brien, which definitely isn’t a pseudonym.

With that to come, this piece will cover something else that we hope is on the horizon: Sunderland AFC’s return to the Championship. This Saturday offers (another) chance for our football club to leap from its League One imprisonment, and make a step toward returning to where we and plenty more feel Sunderland belong.

Much is often made of the financial ramifications of the Championship play-off final. Back in 1998, a certain tussle with Charlton Athletic was referred to in the build-up as ‘the £10 million game’; such has been the incredible growth of the Premier League since then that last year’s showdown between Brentford and Swansea City was widely touted as being worth at least £170 million to the winners.

Far less fanfare surrounds the League One version. The revenue jump between English football’s third and second tier is a long way off what Championship promotion can net a club.

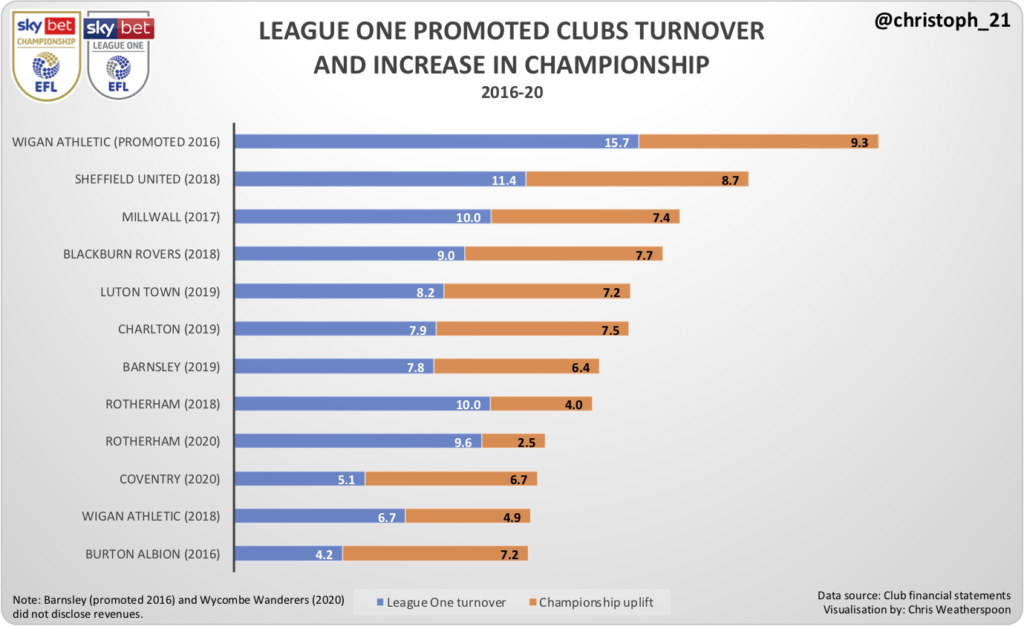

Yet promotion from League One is not wholly without financial reward. A look at the turnover of clubs promoted into the Championship between 2016 and 2020 reveals, on average, an increase in income of around £6.6 million per season. That directly corresponds with the increase in TV rights income that Championship status bring.

In Sunderland’s case, broadcasting income in 2021 was at £5.4m. Promotion wouldn’t result in that rising by as much as the increases shown above. 2021’s TV income was higher than would normally be expected in League One, bolstered by a Covid-19 rescue package that aimed to offset lost gate receipts, from which we and others with large attendances benefited most. Even so, promotion would still see an uplift, and we could expect broadcasting revenues in the Championship to hit around the £9 million mark.

Of course, promotion wouldn’t just increase Sunderland’s broadcasting revenues. A higher standard of football offers greater commercial opportunities, and scope to (further) increase ticket prices and gate receipts.

Three years ago, when the murk of Madrox had yet to be uncovered and fans almost universally bought into the purported project, the club recouped commercial income of over £10 million. Assuming reasonable uplifts in other revenue streams, Sunderland might expect annual revenues in the Championship to land around the £27 million mark.

But while revenues would increase upon a return to the Championship, the likelihood is they’d be outstripped by an increase in costs. Or rather, they would be if the club had any real intention of doing anything beyond surviving relegation each season.

The Championship is increasingly referred to as the most financially fraught league in world football, and with good reason. In 2021, clubs’ average wages-to-revenue hit 148 per cent, an eyewatering figure. Scarier still, collective net debt in the league hit £1.5 billion. Much of that is interest-free and owed to club owners, but it still highlights just how much it costs to run a club in a league full of teams desperately striving for the riches of the Premier League.

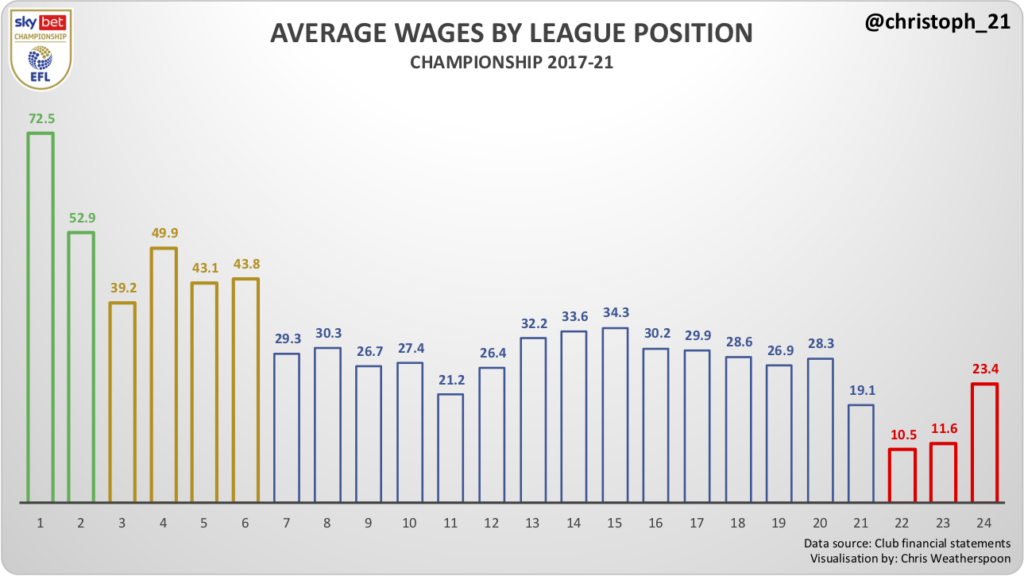

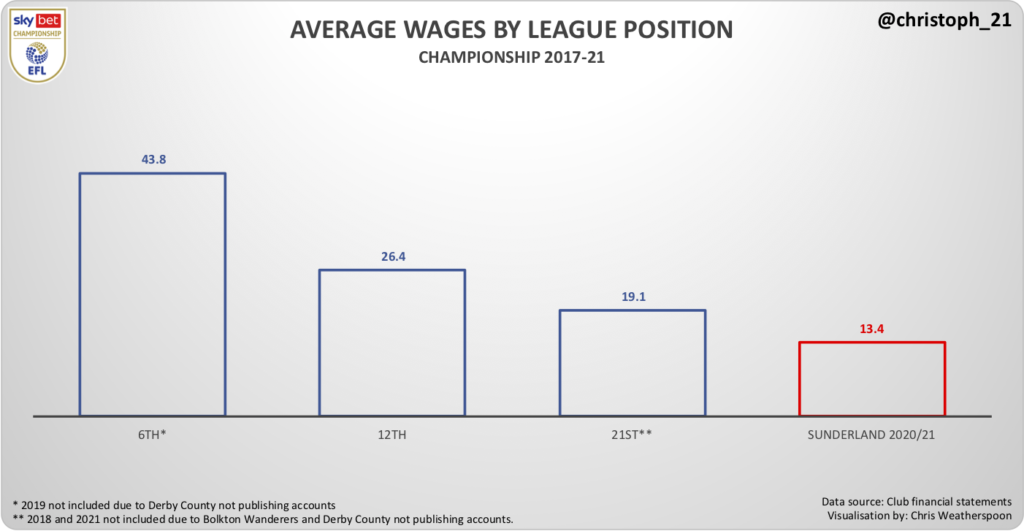

A look at the average wage bills of each position in the Championship table across the last five years is indicative of the costs involved. On average, mere Championship survival has required an annual wage bill of £19.1 million. Set against Sunderland’s 2021 wage bill, that would be a 43 per cent increase, and would just about consume all of the additional broadcast income we covered above. In reality, the club’s wage bill has fallen further in the current season, so an even greater increase would be required in order to hit that level of spend.

Just settling for survival is unlikely to appease many supporters of our club for long, and rightly so. Competing further up the Championship table would thus mean even greater investment in the playing squad is required. In the Championship, as across football in general, higher wages equal higher league finishes.

That isn’t an exact rule, and the above shows that from outside the play-offs to lower mid-table a number of clubs are competing with similar staff costs. Yet those levels are all up and around the £27 million that our club can expect to earn in income in the Championship. In reality, most clubs in the division now pay out more in wages than they receive in income – and that’s before taking any other costs into account.

Sunderland fans, and hopefully the club, harbour ambitions of a return to the Premier League as soon as possible. Yet to even broach the play-off spots in recent seasons has required a wage bill of nearly £44 million.

That is not to say clubs have to just spend big on wages to move up the table – and the reason the teams in third place over the last five years spent less on average than some below them is down to the exceptionally well-run Brentford – but it would require very savvy transfer dealings and excellent management of the club to compete at the top end of the Championship without serious investment.

Indeed, one area clubs are increasingly looking to focus their business model around involves the recycling of players for profits. The ‘Brentford model’ is arguably the pioneer: they buy low, sell high, and replace with good or better. In the five years leading up to their promotion to the Premier League, the Bees booked £119 million in transfer fee profits against traditional revenues of just £70 million.

Brentford are an extreme (positive) example, but it’s true that player sales have become increasingly important to Championship clubs. Collective profit on sales has inched up to around £250 million per season, an average of over £10 million per club.

It wouldn’t be surprising to see Sunderland adopt a similar model if promoted, though how much scope there would be to do so is debatable. The asset-stripping of the club’s academy prospects by the not-quite-former owners is now well-documented, and a number of this season’s key performers are either on loan or short-term contracts. Players like Ross Stewart, Dan Neil and Dennis Cirkin would probably top the list of those with chunky re-sale values, but the hardest part of such a model is ensuring you find even better replacements and improve rather than decline.

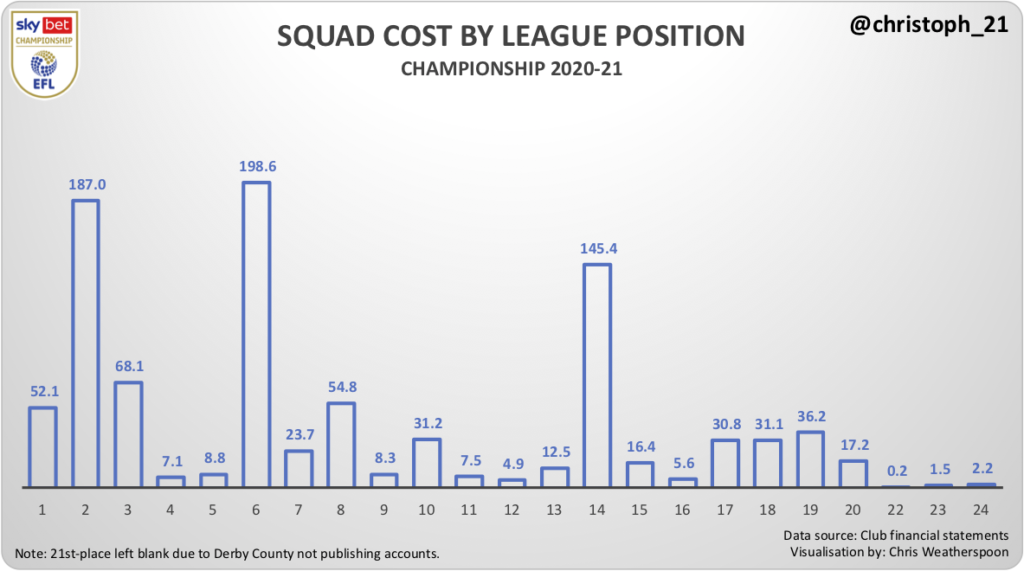

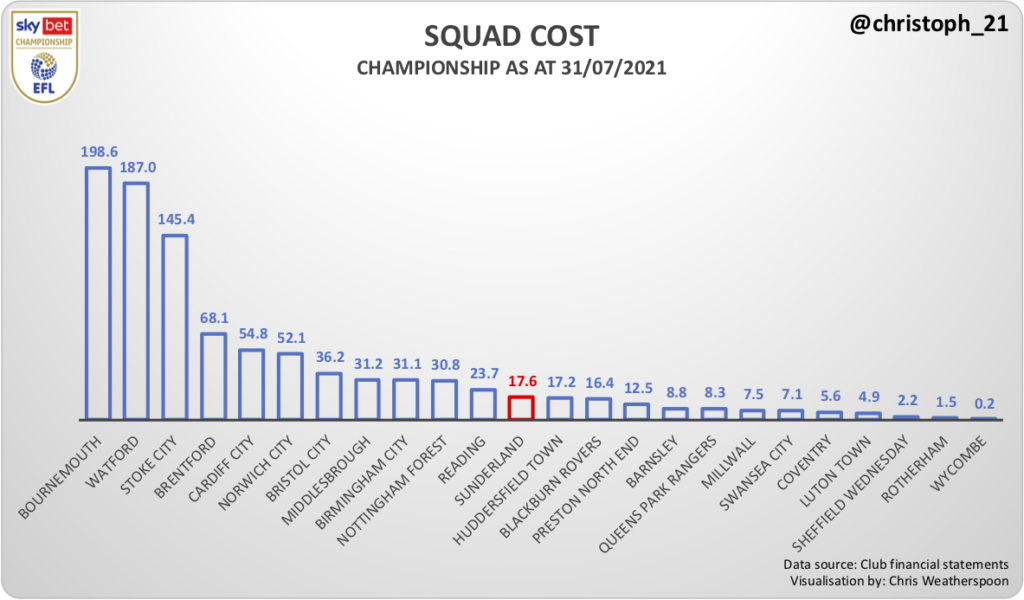

Moving back to costs, a poorer proxy of league position than wages is how much a club spends on transfer fees. A look at last season’s Championship table according to squad values shows little correlation between spend and league position – though it’s interesting that the three clubs with the lowest squad value at the end of the 2021 season had all been relegated that term (note: Sheffield Wednesday accounts go to July 2021, so their value, column 24 in the graphic below, dropped a fair way through disposing of players post-relegation).

Yet while a club’s transfer spend mightn’t correlate to glory – Manchester United, for example, currently boast the most expensively assembled squad in England – these figures do at least give an indication of the level of investment and/or transfer market success Sunderland will require if promoted.

Ordering squad costs by value shows a huge disparity between several former Premier League clubs and the remainder of the division. Stoke City evidently eked out little worth from their hefty fees (and have impaired several players’ values accordingly), but there’s a significant gap across the division.

Including Sunderland at their squad’s cost in the latest accounts actually pits us mid-table, but this is mostly by virtue of the club continuing to pay the likes of Lee Cattermole and Bryan Oviedo despite them having left nearly three years ago (and the accounting treatment applied here is questionable). Strip them out and you’re closer to a value of £5 million, the bulk of which went on Will Grigg.

An up-to-date squad cost value for the club at the end of this season would likely land as low as £2-3 million, well below the Championship average of £40 million. Again, this doesn’t mean the club would need to spend up to that level to achieve success, but it does highlight the gap in finances between League One and the division above.

It’s long been recognised that much of the Championship’s wage inflation problem stems from the presence of parachute payments. Where Sunderland spent theirs poorly or, as has been done to the death by yours truly, had theirs snaffled by otherwise insufficiently-resourced owners to buy the club, most clubs in recent years have put theirs to good use. The last four clubs to be promoted automatically from the Championship have all been in receipt of parachute payments.

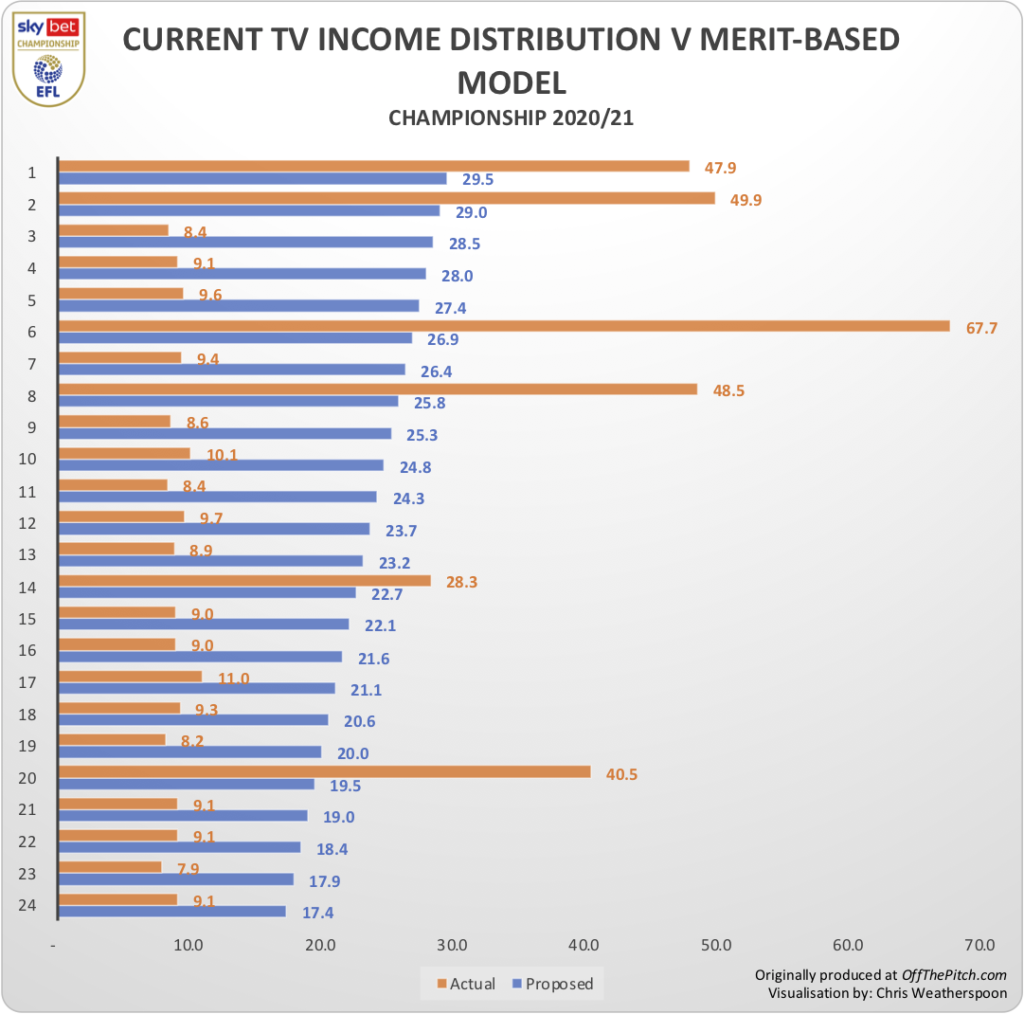

That helps explain why those clubs are able to spend so much on wages (though it’s worth noting the above table also includes promotion bonuses that wouldn’t ordinarily be payable). It also explains why the EFL is pushing to abolish parachute payments and revert to a merit-based distribution of TV money.

Doing so would actually be a boon for Sunderland. Having enjoyed the, ahem, benefit of our own parachute payments that have now run out, moving to a merit-based system would increase the monies on offer for a majority of clubs in the Championship, help level the playing field and, for owners, likely mean the club is less reliant on external funding.

Where Championship clubs currently average around £9 million in broadcast income (not including those receiving parachute payments), an estimate of distributions under a merit-based model would have seen even the Championship’s bottom side take home in excess of £17 million in 2021. TV income would have ranged from there to around £30 million for the league-winners, and clubs would generally be able to arrest the huge losses they collectively make each year, especially given another proposal is for the EFL to introduce a robust 70 per cent cap on wages.

For now, the parachute payment model remains in place, and it’s unlikely to disappear before next season. That would put Sunderland at a competitive disadvantage should promotion be achieved this weekend, but if we were able to survive next season, the opportunity to compete further up the Championship table may well grow.

Championship clubs made a collective loss of £224 million in 2021, and combined losses since 2017 mirror that £1.5 billion debt figure. In essence, owners fund losses, while forever striving for a trip to the promised land.

At least two of Sunderland’s owners will be praying for victory this weekend in order to try and bump up the sale price of their shares in the club. The honest truth is that, in its current state, arrival in the Championship is more likely to make an owner’s job costlier than it is to boost his bank balance.

Any uplift in the value of Sunderland AFC will not be because the Championship is a division where the financial landscape is more appealing. The opposite is true. Instead, an improvement in the value of our club would only arrive by virtue of us being one step closer to the Premier League – and will require a willing buyer to assess just how much they’re willing to risk in order to get there.