The end of April is rarely quiet at Sunderland AFC, with 2023 proving no exception. What plenty expected to be a tame, uneventful end to the season has instead morphed into a toing and froing battle for a play-off berth, and a potential promotion that even the most optimistic of us failed to foresee being in our sightline nine months ago.

While Aprils on the field have long been stressful and dizzying, the month has seen an increased focus off the field too in recent years. Sunderland AFC – or, to be more precise, the company named Sunderland Limited, which ultimately owns the football club and all of its assets – is required to publish its annual financial statements by 30 April, an event that has received significant attention over the last few years.

Accordingly, those financial statements dropped into the public sphere early last Friday evening. As things in the industry go, that’s quite late; Sunderland were the 76th of 92 Football League clubs to publish their accounts for the 2021/22 season. That owes to the club’s accounting year end date being 31 July – most other clubs have a 30 June reporting date, aligning with the end of player contract terms and ensuring no overlap across seasons.

That has always made Sunderland’s finances a little trickier to analyse when comparing with others, but the effect was especially pronounced this time around. Owing to the scheduling of the World Cup, the 2022/23 EFL Championship kicked off on the final weekend of July. That means these accounts cover not only all of last season in League One but, oddly, this term’s opening day hosting of Coventry City too.

Whether Sunderland opt to shift their reporting date to June, as plenty of other clubs have, remains to be seen. In the meantime, we do what we can with what’s available to us.

In the spirit of that, what follows is a detailed run-through of the club’s latest financial results, how they compare historically and with other clubs (both in League One and beyond) and various general observations that hopefully flesh out a broader picture of how our football club is currently operating.

We hope you find it interesting.

Profit/Loss

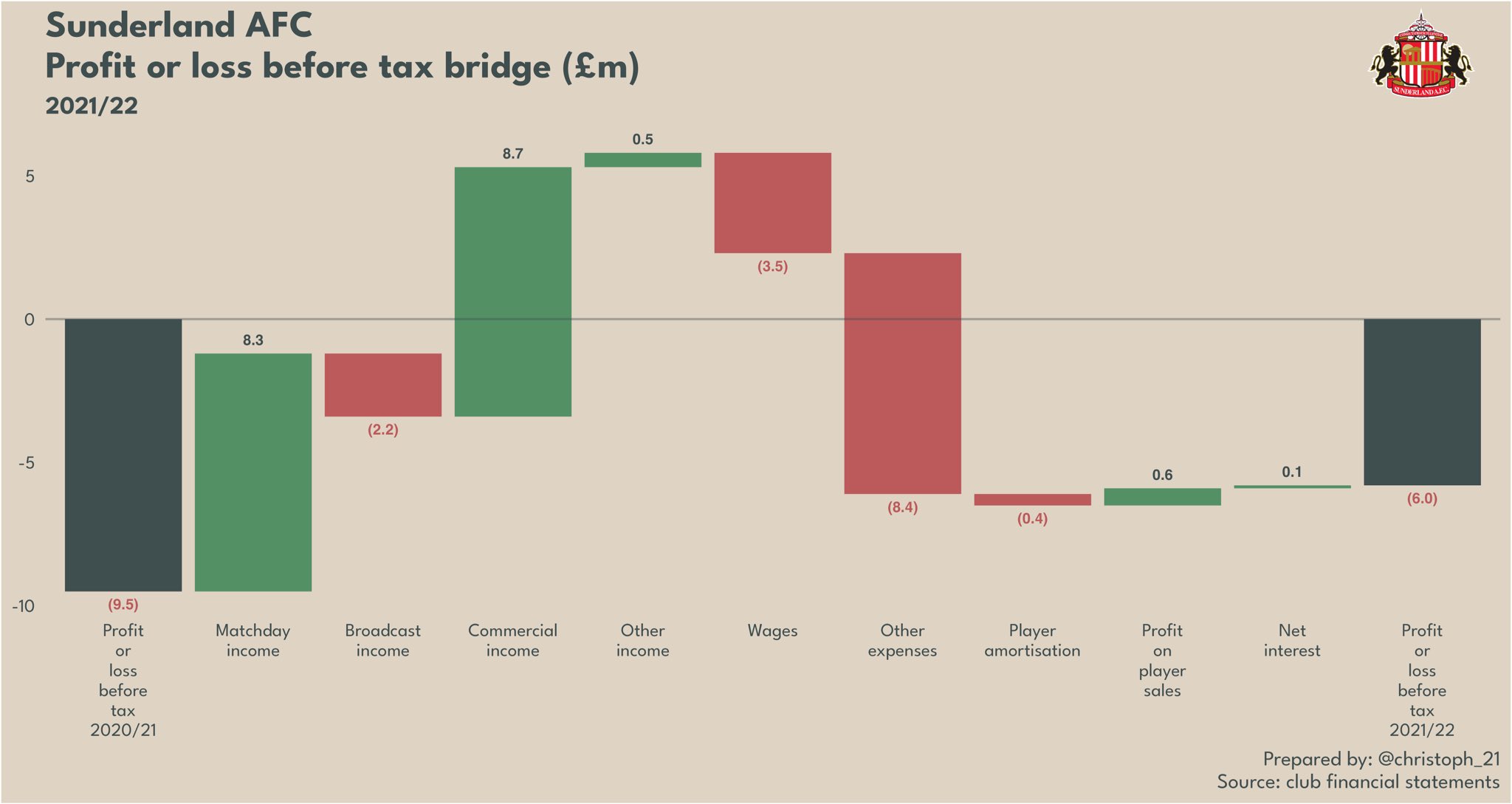

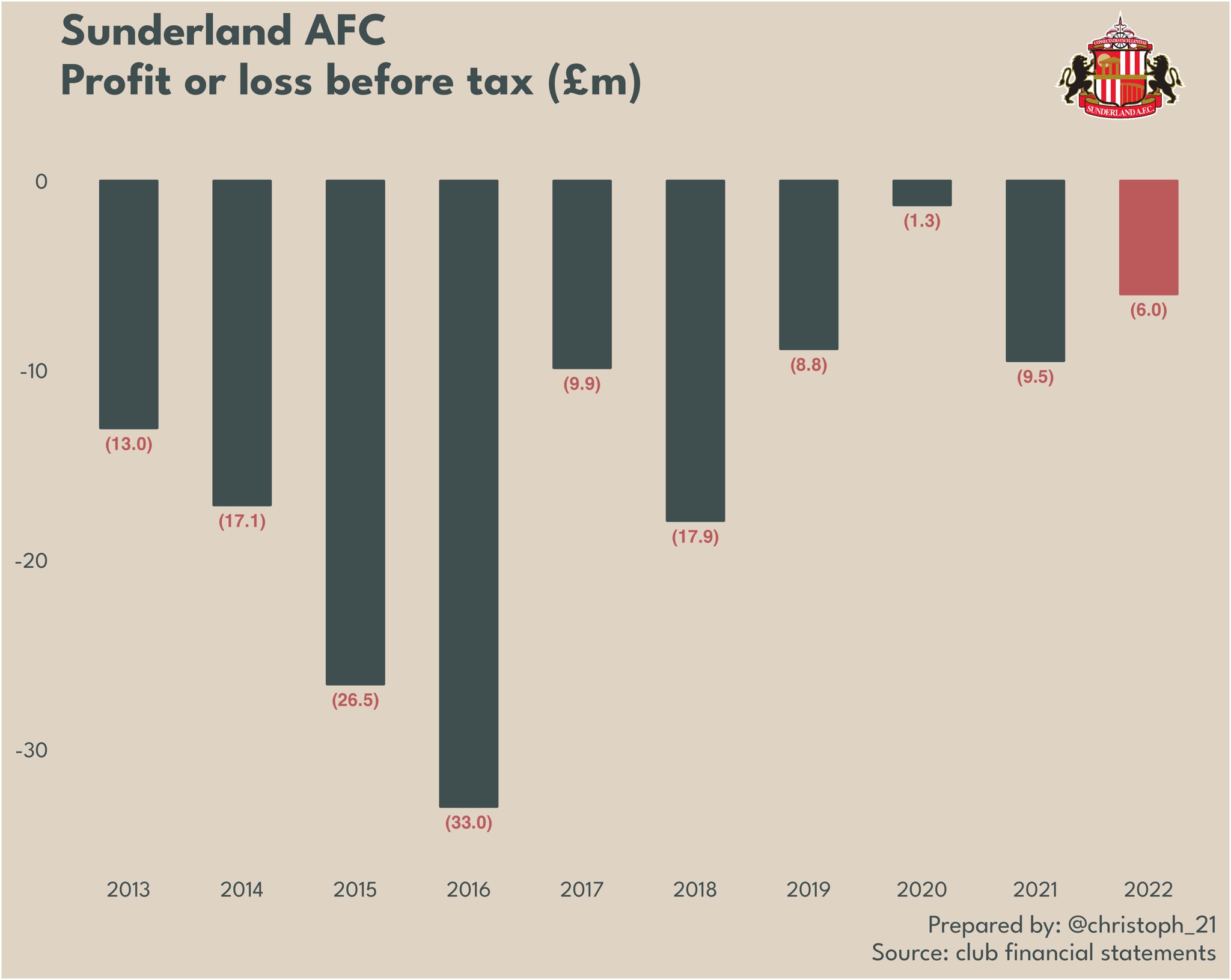

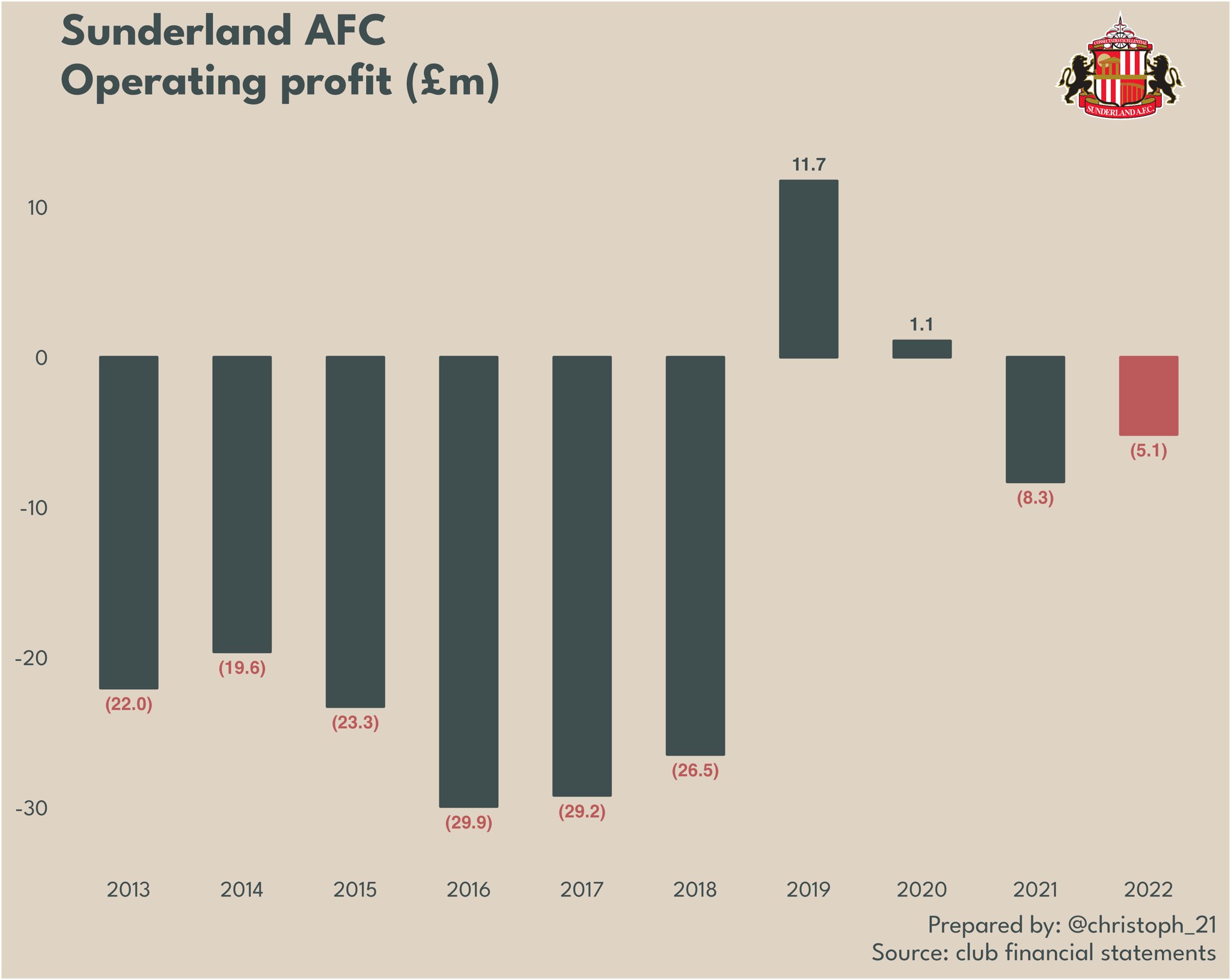

Sunderland’s £6m pre-tax loss was an improvement of £3.5m on their 2021 figure, but still the club’s 16th consecutive loss-making year. 2022 was the second-lowest loss in that period, though the club would have booked an £11.7m profit in 2019 if its former ownership group hadn’t written off £20.5m of the monies they loaned from the club in order to facilitate its purchase.

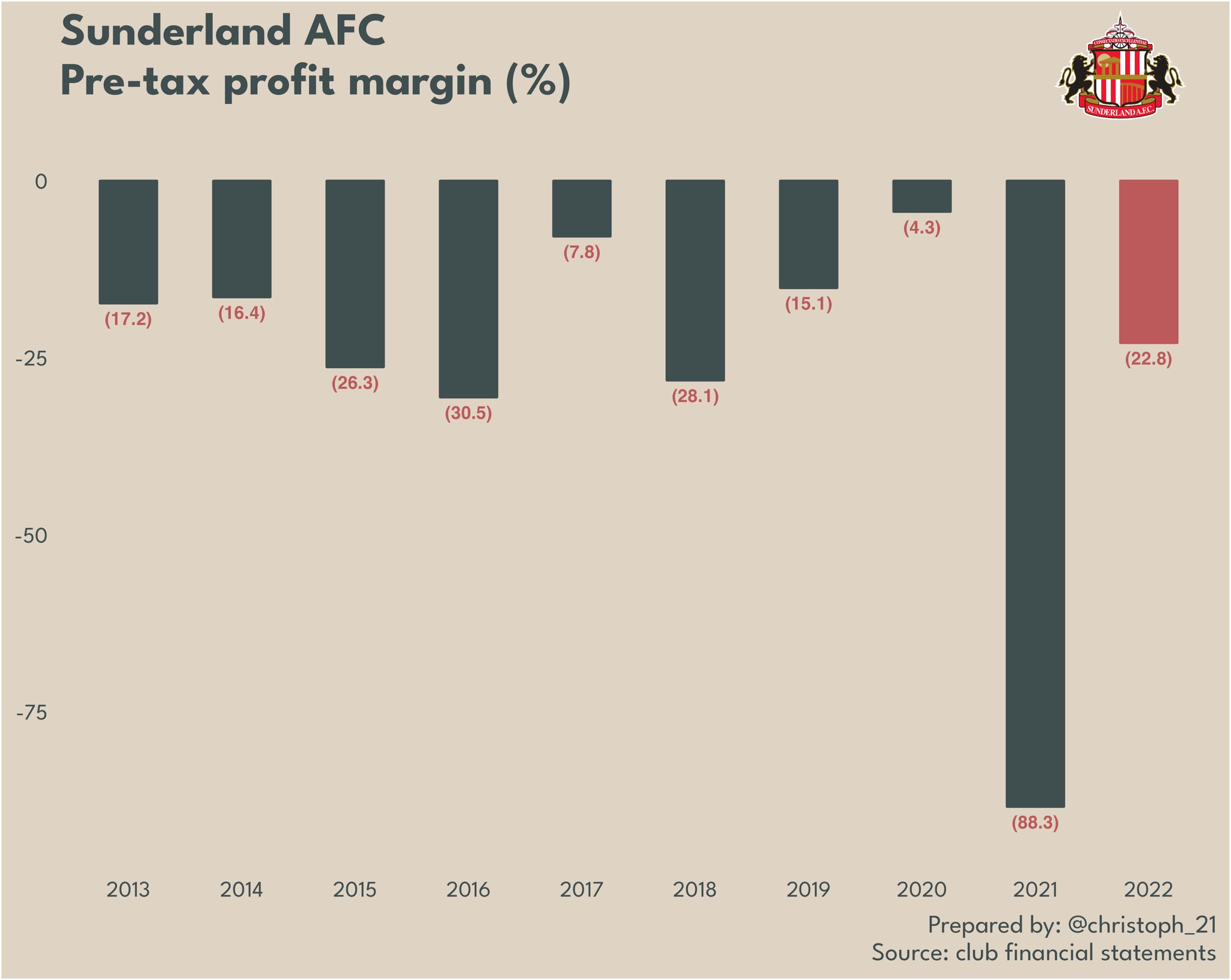

In terms of the pre-tax loss relative to the club’s revenue, 2022 represented a huge improvement on a dreadful year prior. Sunderland’s pre-tax profit margin of negative 23% was actually better than a number of years when the club was in the EPL.

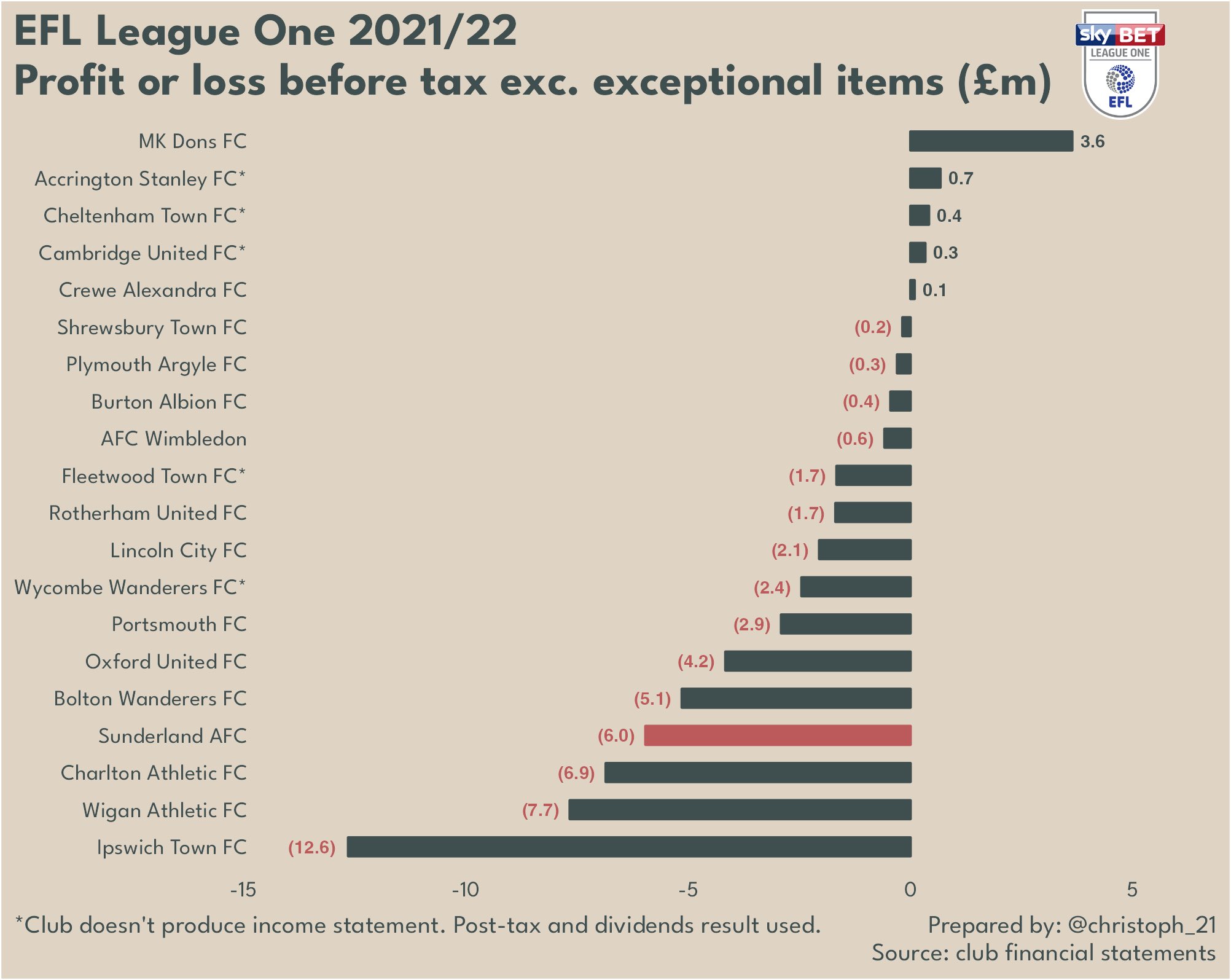

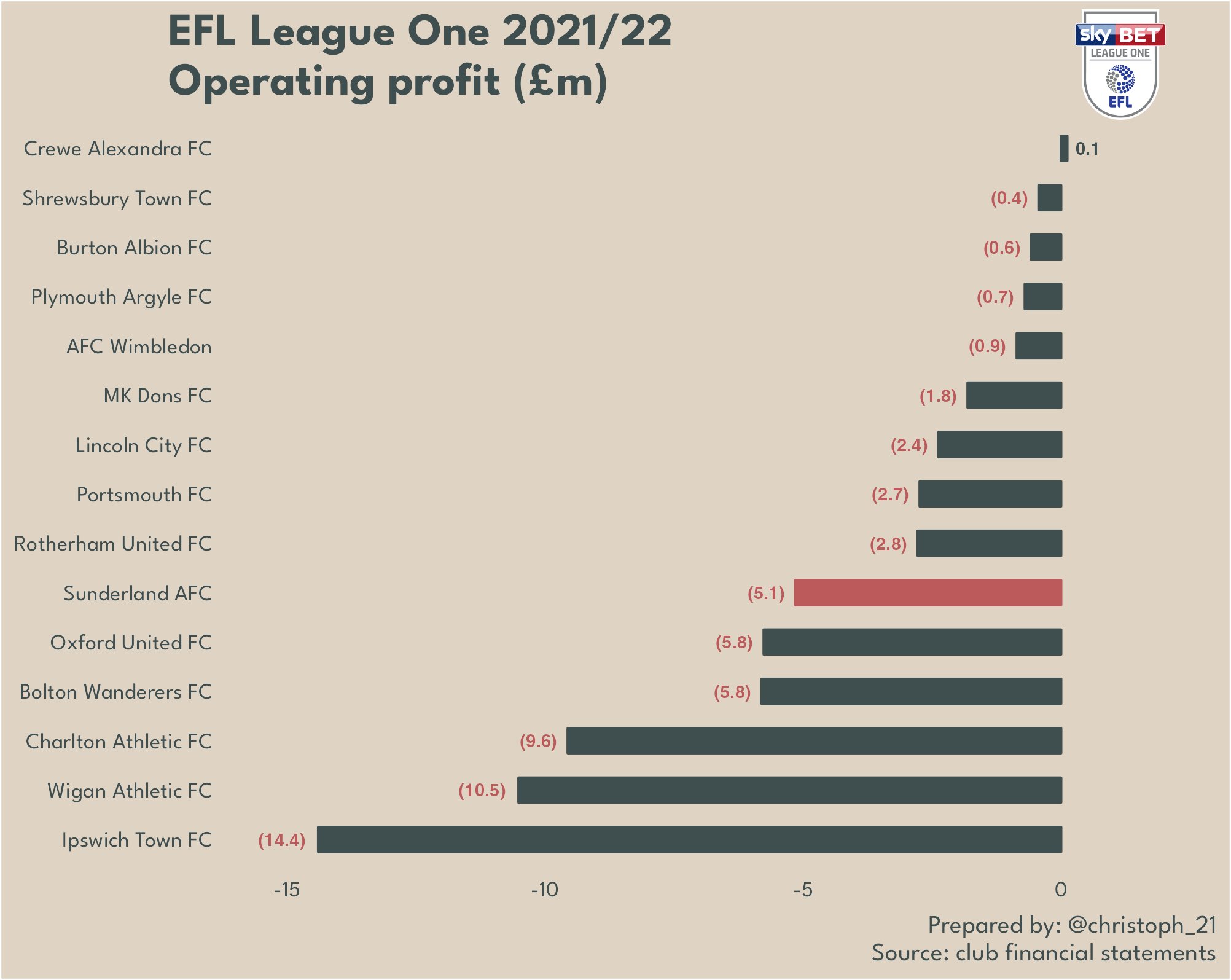

Sunderland’s loss was the fourth-largest deficit in League One last year (four clubs are still to publish results at the time of writing). That said, the club were some way behind Ipswich Town’s hefty £12.6m loss, as the Portman Road outfit’s new owners invested heavily in the playing squad.

Sunderland lost the most money in the division in 2021, so last year showed improvement in that respect too. Yet while their reduced losses are (clearly) a positive, the £6m deficit shows once again that a club of Sunderland’s size, with the infrastructure it boasts, simply could not be sustainable in the third tier of English football.

In terms of operating (day-to-day) performance, Sunderland lost £5.1m. Other than years where the club received parachute payments, this has been common for the club (and is for many others too), and last year was comparatively low by recent standards.

Only one League One club – relegated Crewe Alexandra – booked an operating profit in 2021/22, and Sunderland’s loss in this regard was ‘only’ the sixth-worst in the division.

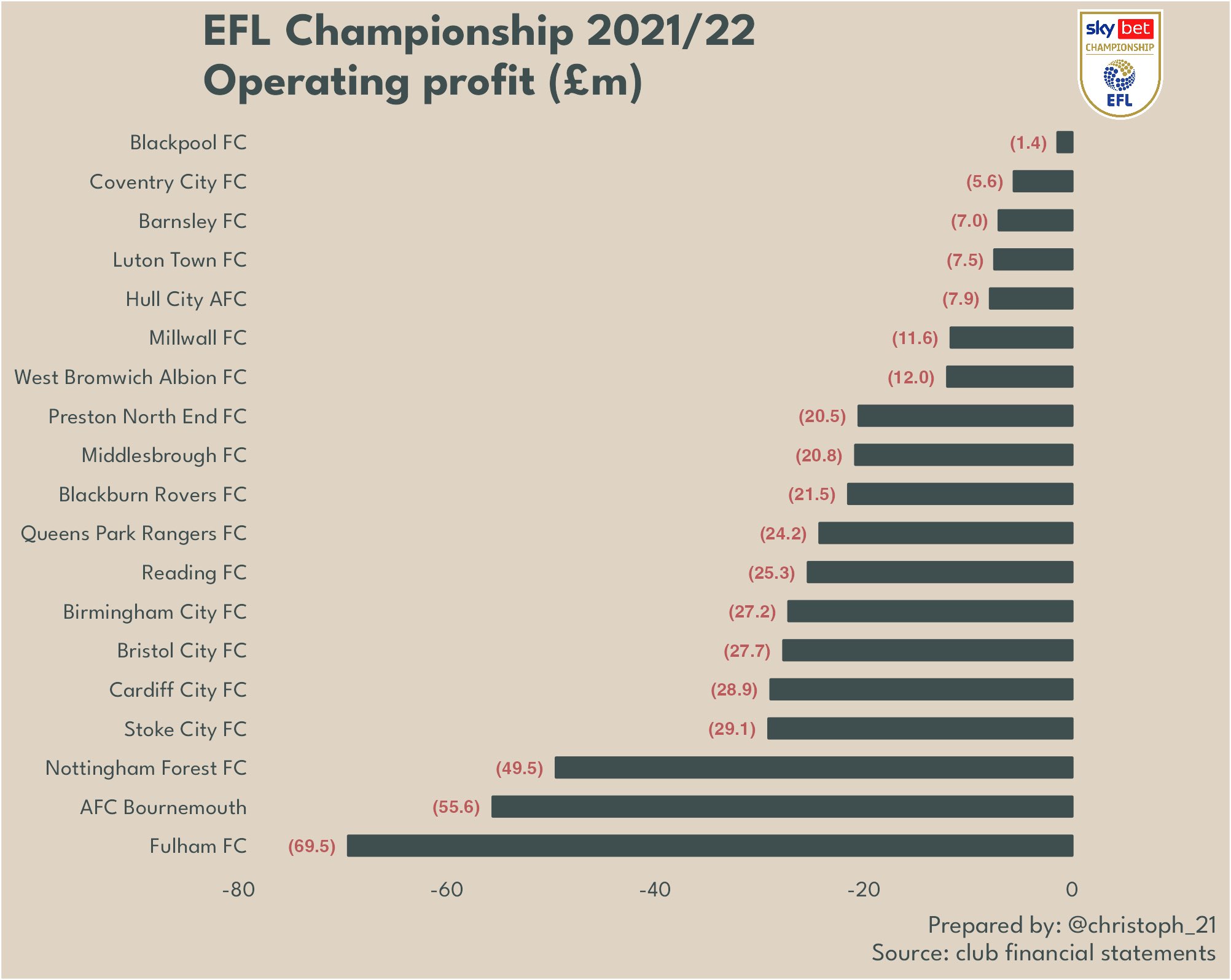

That £5.1m loss was also significantly below the operating losses seen in the Championship, owing to the chunky wage bills clubs carry in the second tier in the hope of achieving promotion to the promised land of the EPL.

Turnover

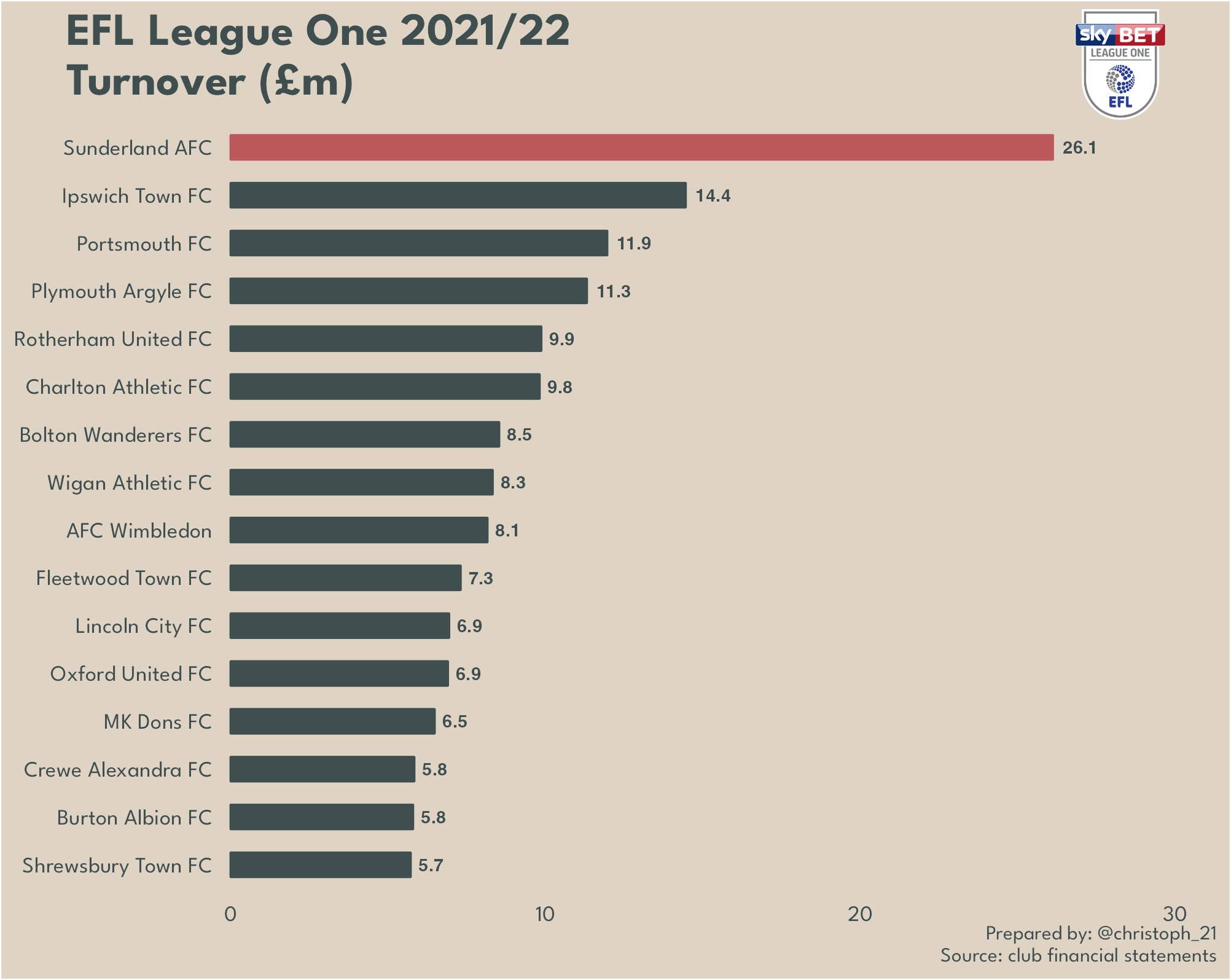

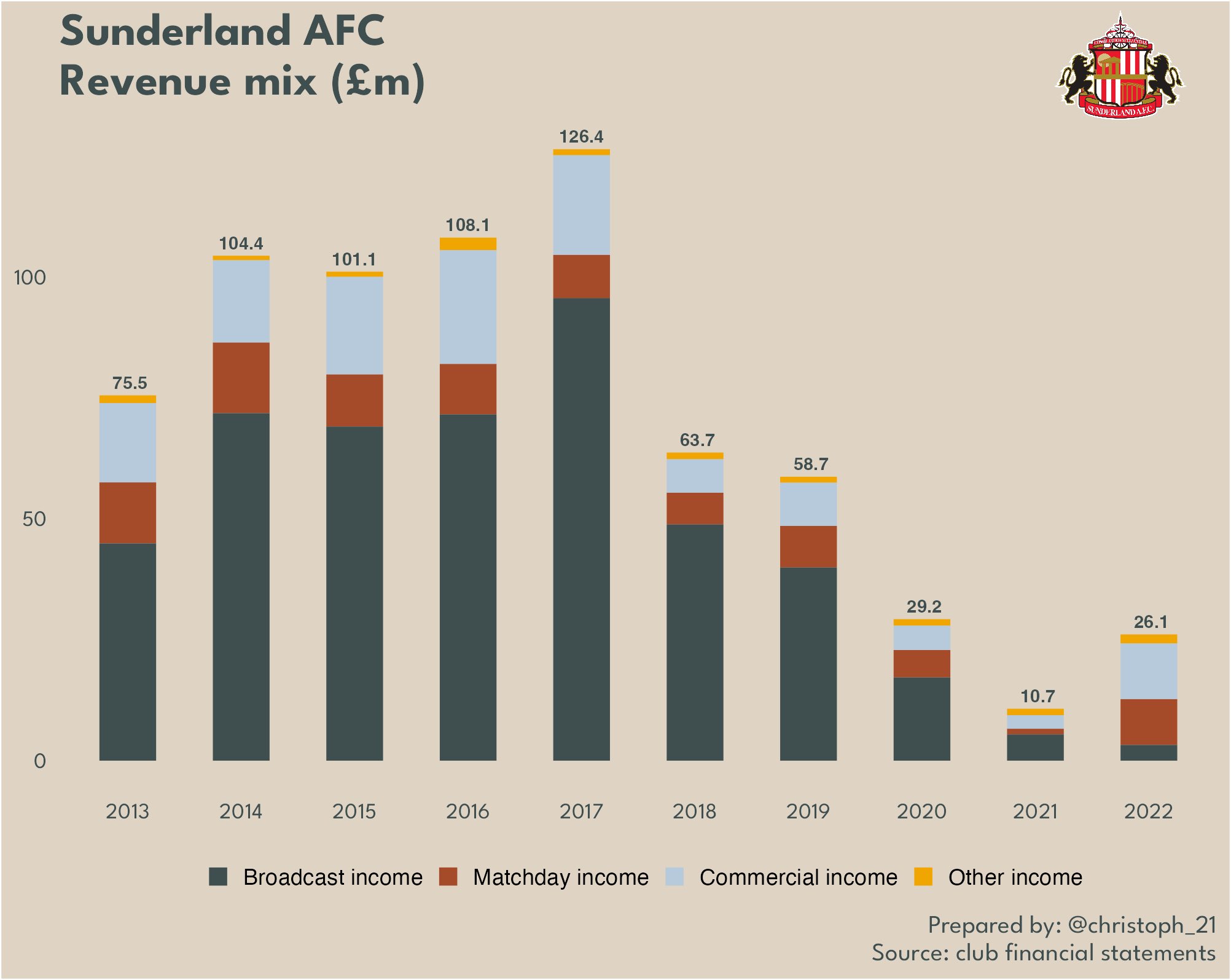

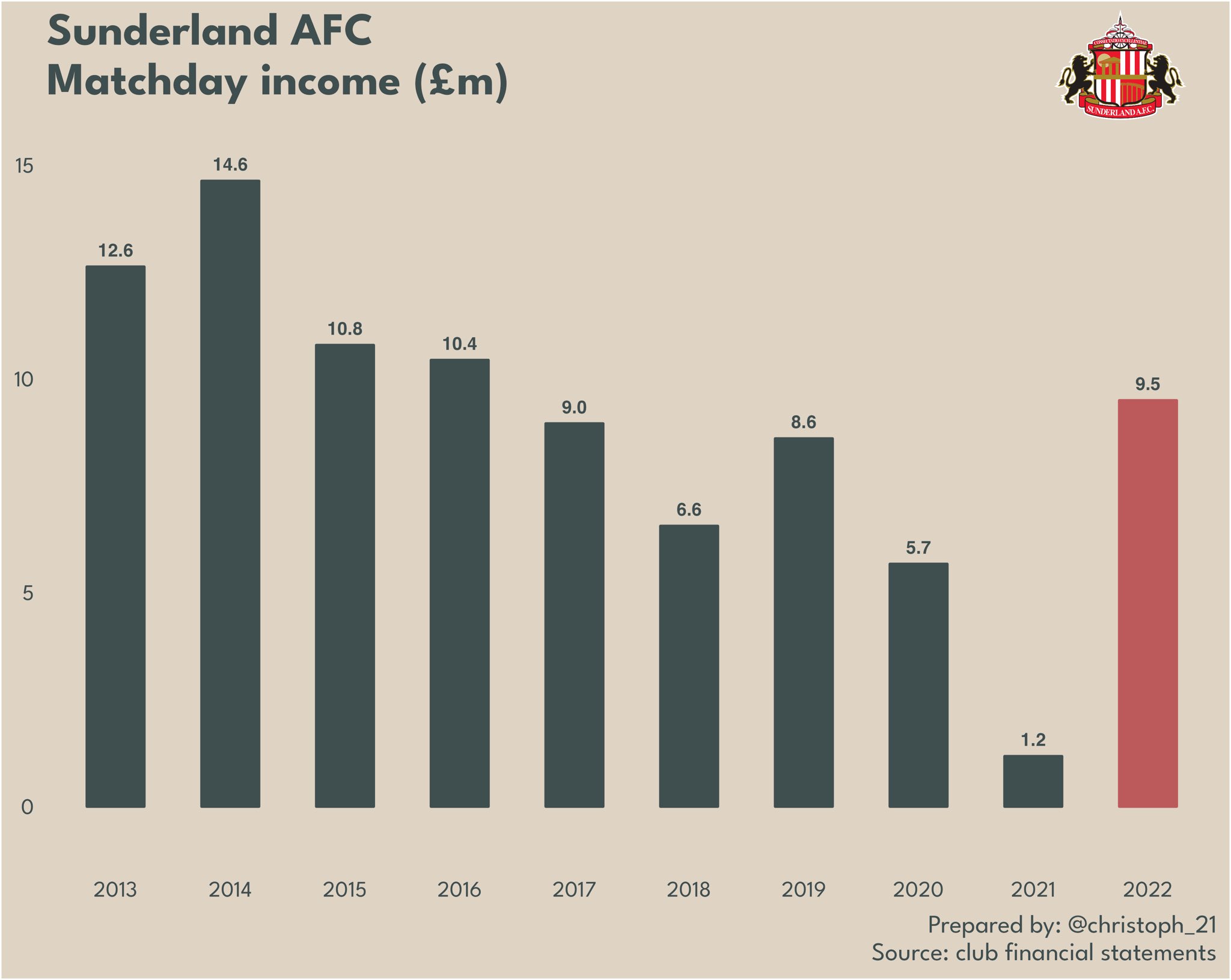

Sunderland’s reduced loss in 2022 owed to club revenues leaping up, as fans returned to stadia with the end of Covid-19 lockdowns. Turnover of £26.1m represented a 161% increase on 2021 – but was still £100m below the club’s record turnover in 2017 (a year when the club was relegated, no less).

That Sunderland could bank its all-time highest income in a season where they failed so badly is indicative of the huge wealth gap that exists in modern football. The club’s income has fallen by 79% in just five years.

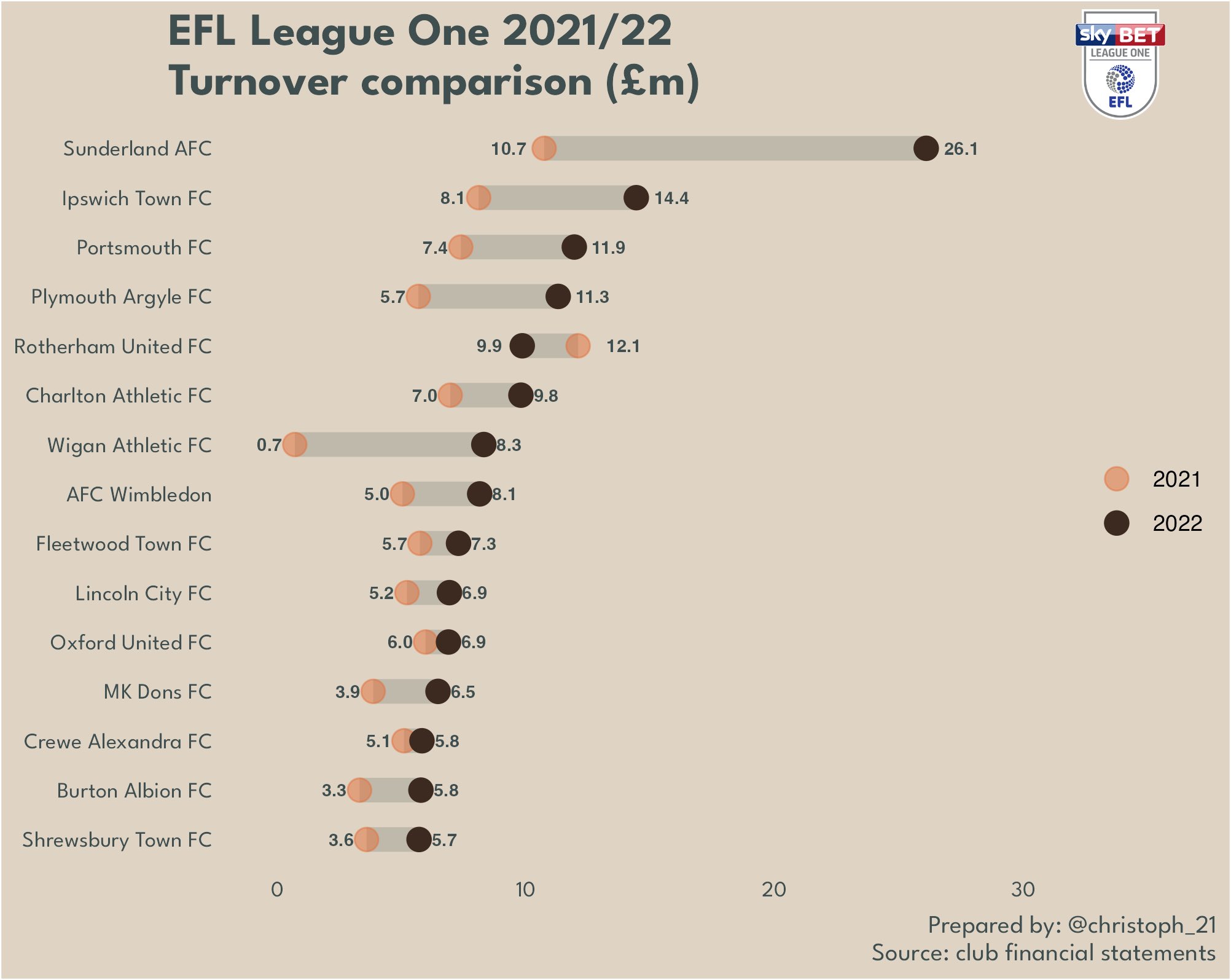

Sunderland had comfortably the highest income in League One, well ahead of second-placed Ipswich Town (£14.4m). Those two comprised the top two in the second tier in 2021 as well, though the gap was far smaller. Then, Sunderland’s £10.7m income outstripped Ipswich by just £2.6m, against an £11.7m difference in 2022.

Other than recently relegated Rotherham United, all League One clubs improved income in 2022, but Sunderland’s increase was far greater than others, reflecting the size of the club’s fan base. A look at the year-on-year change in income for those League One clubs that disclose revenues shows just how harmful to the club’s finances the pandemic was.

(Note: Wigan Athletic’s 2021 figure only covers from January to June, owing to the club formerly being in administration.)

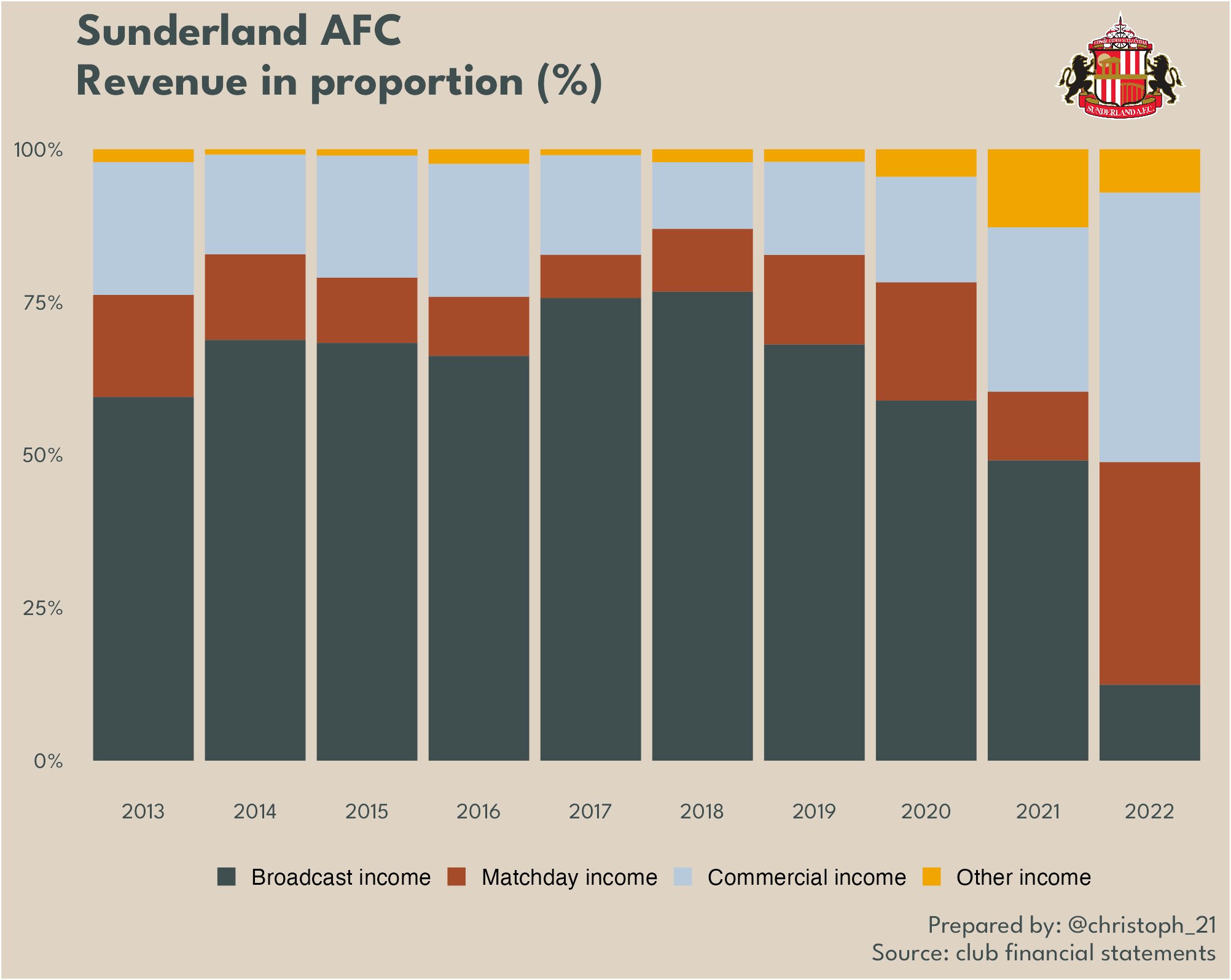

For the first time in a very long while, broadcast income didn’t comprise the majority of Sunderland’s turnover. Broadcast’s share of club revenues was just 12% in 2022, reflecting paltry TV distributions in League One. The club was much more reliant on matchday (36%) and commercial (44%) income than has been the case for nearly two decades.

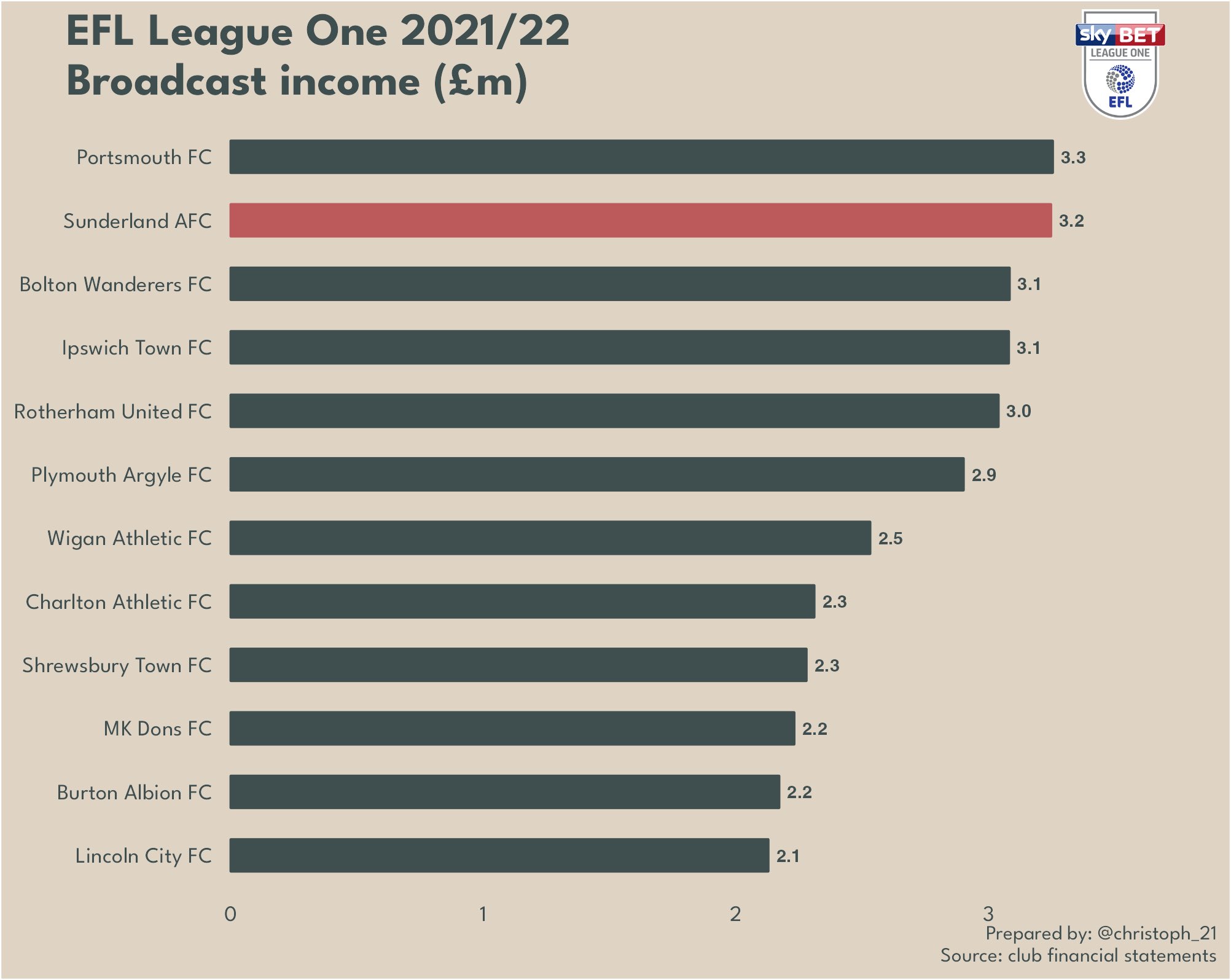

Sunderland enjoyed a fair bit higher broadcast income in 2021 than many League One clubs, as the club received a greater distribution from the EFL to offset gate receipts lost to Covid (Portsmouth were a similar beneficiary).

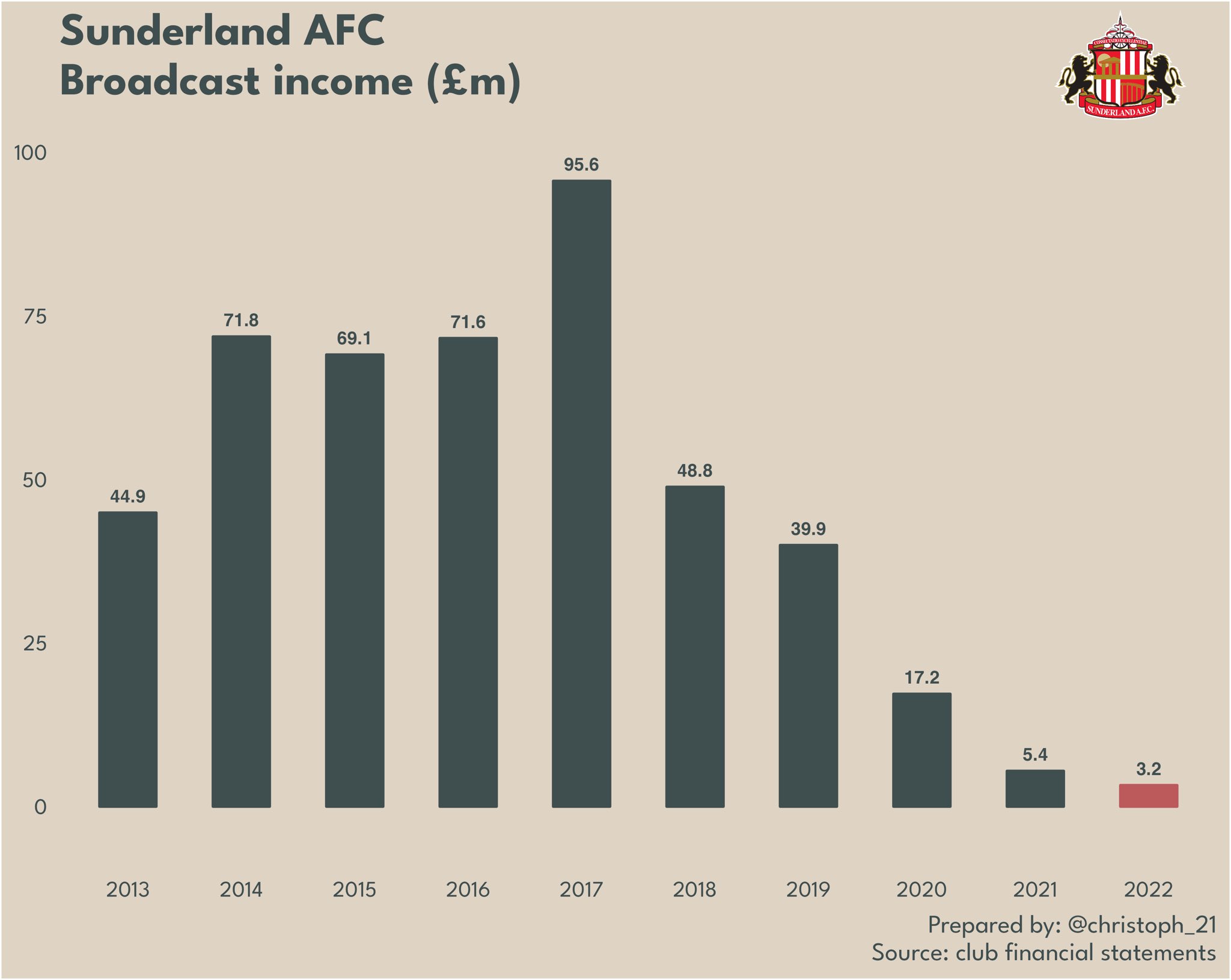

Without that increased handout, TV money fell to £3.2m, even with a successful play-off run and a televised first game in Championship falling into the accounting period.

A look at the club’s 10-year broadcast income record shows how, in some ways, Sunderland missed the boat; the club enjoyed only one year of the EPL’s bumper TV rights deal that covered 2016-19, and the amounts distributed to top tier clubs have only increased since.

Back in the present day, Sunderland still enjoyed the second-highest TV income in League One last season, but the amounts on offer are so small that the income disparity between top and bottom isn’t so vast as in the EPL, where, among other things, clubs are awarded income on merit. No such mechanism exists in the EFL, though that’s expected to change in the near future.

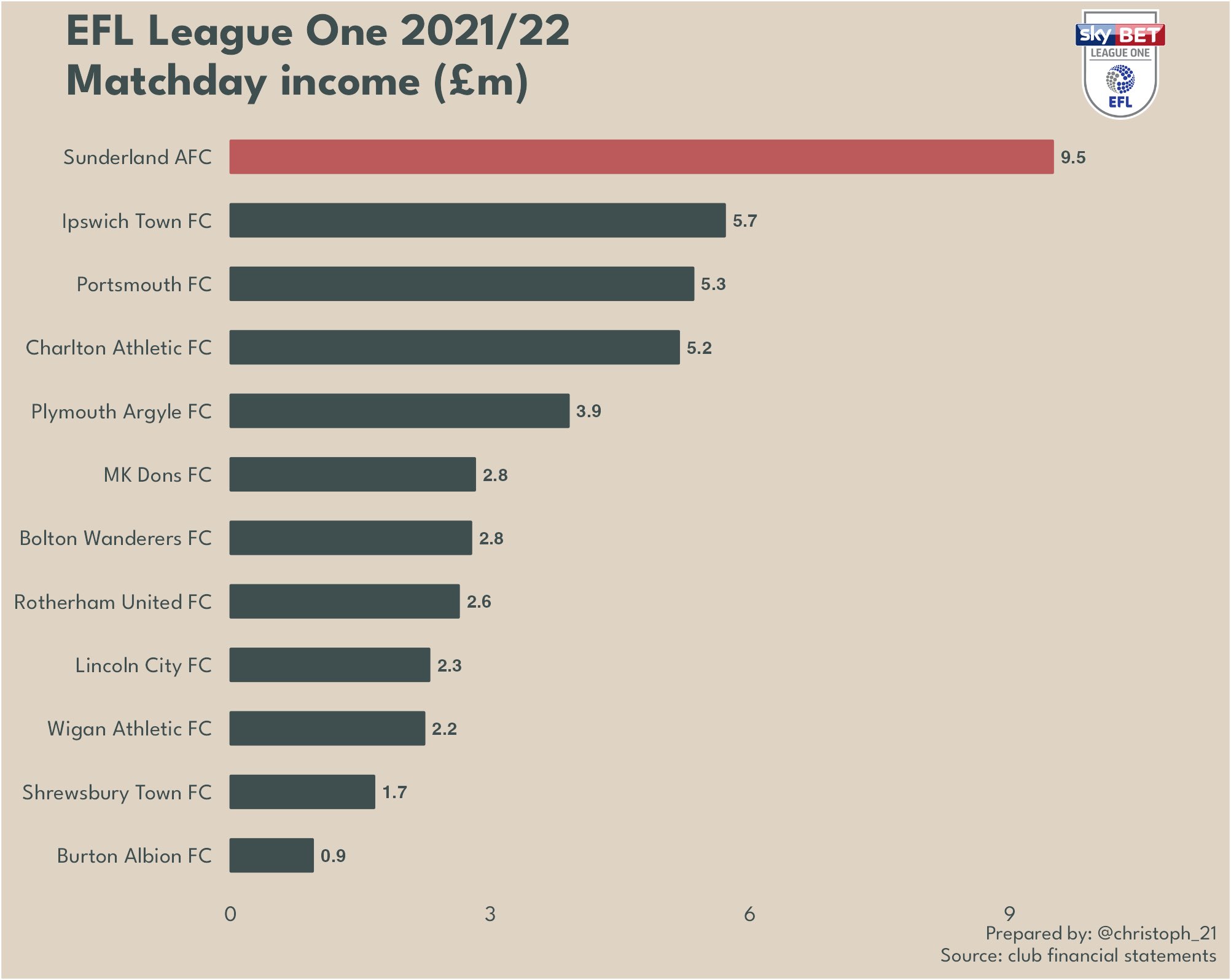

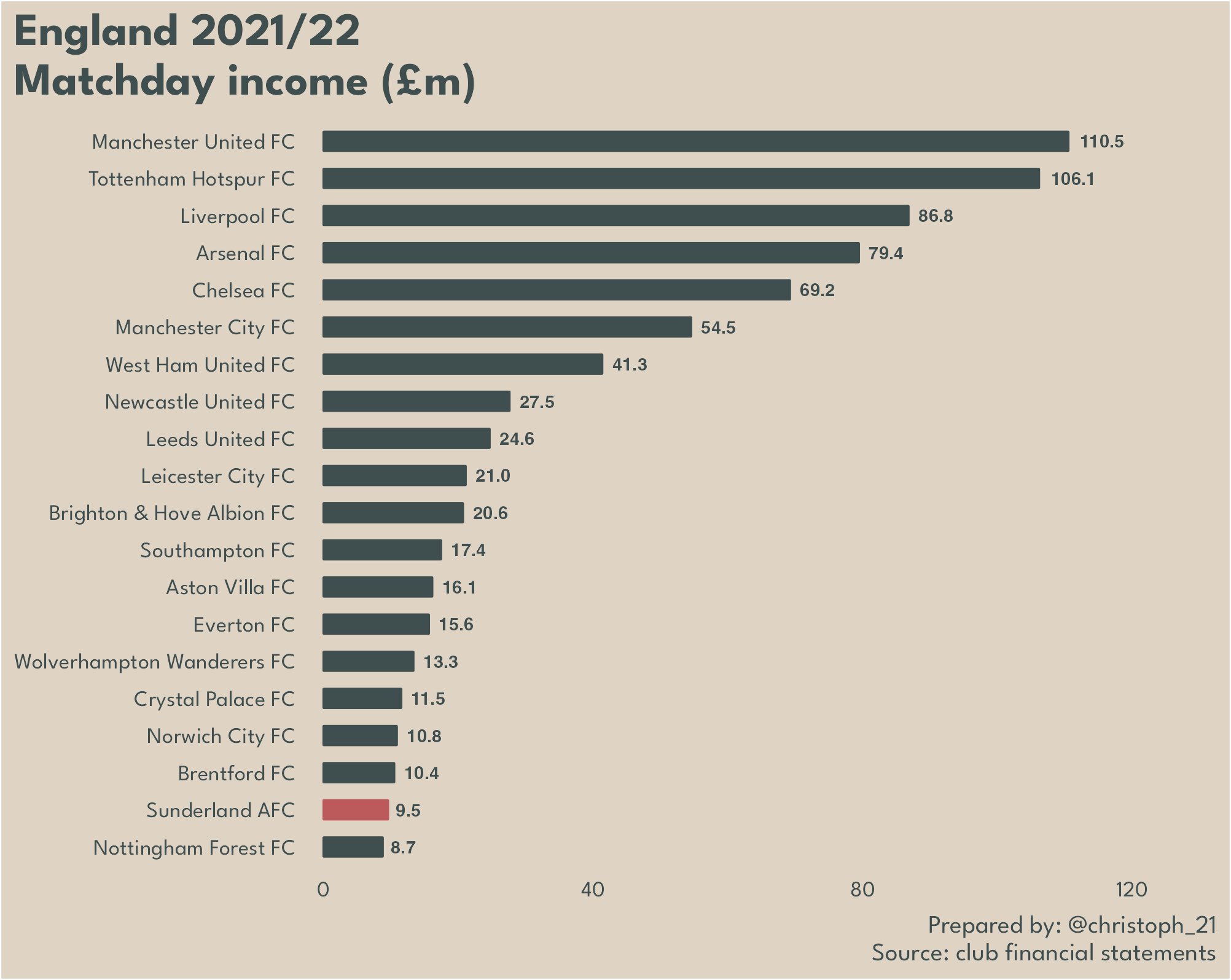

With TV income tumbling, Sunderland’s fan base became more important than ever. The club benefited from post-lockdown enthusiasm, selling 24,713 season tickets in League One. That helped generate gate receipts of £9.5m, which was a higher figure than the club’s most recent season in the EPL.

Correspondingly, SAFC’s matchday income was comfortably the highest in the division. It was also the fourth-highest in League One history, only surpassed by Leeds United (twice) and Southampton during their respective stints in the division over a decade ago.

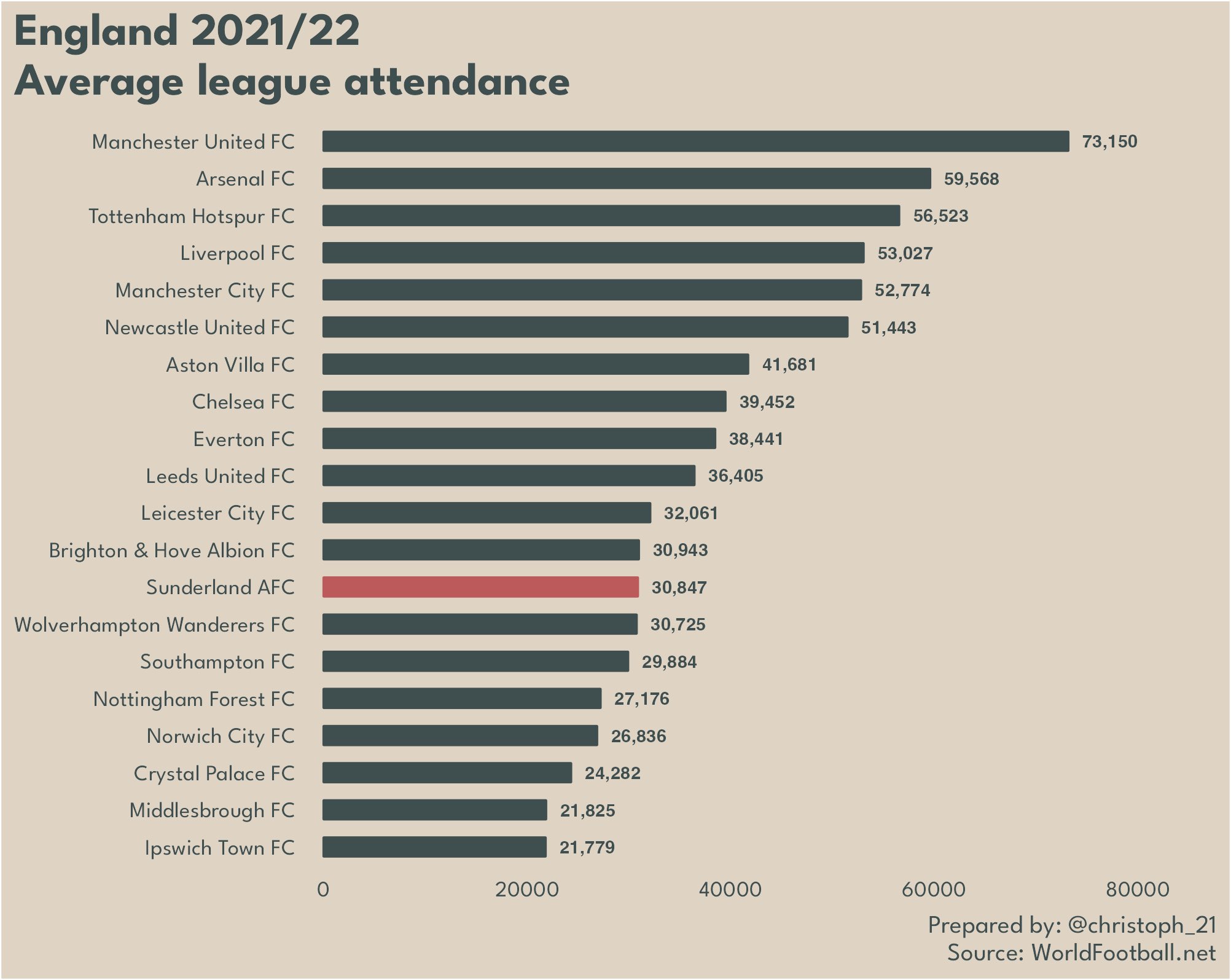

Sunderland’s £9.5m was also a higher matchday income figure than any Championship club managed last season. Overall, Sunderland had the 19th-highest gate receipts in England last year on the back of the 13th-highest average league attendance (30,847). That underlines two things: the club’s excellent supporter numbers even in spite of its lowly status relative to the past, and the difficulties of generating big sums from fans in the lower leagues.

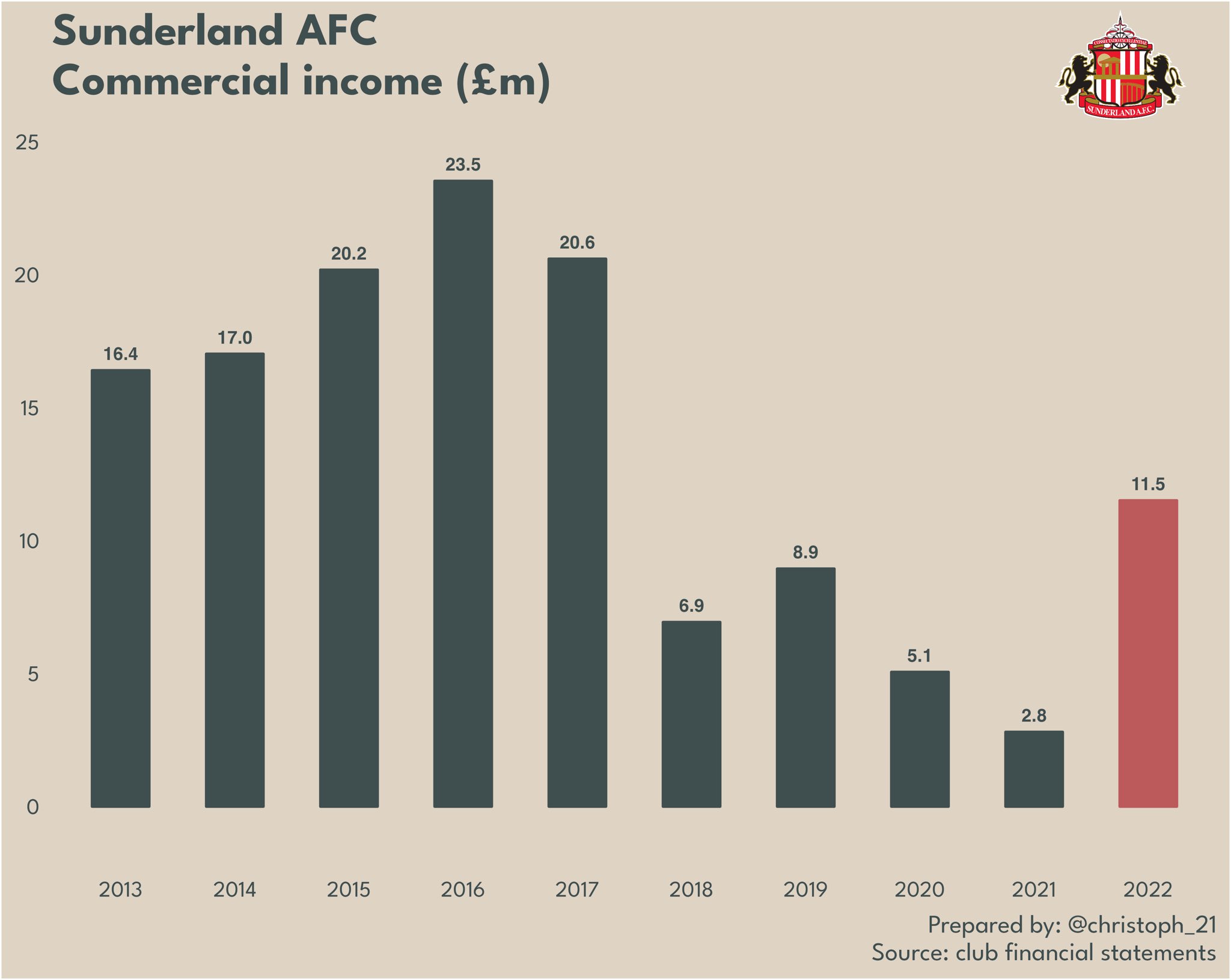

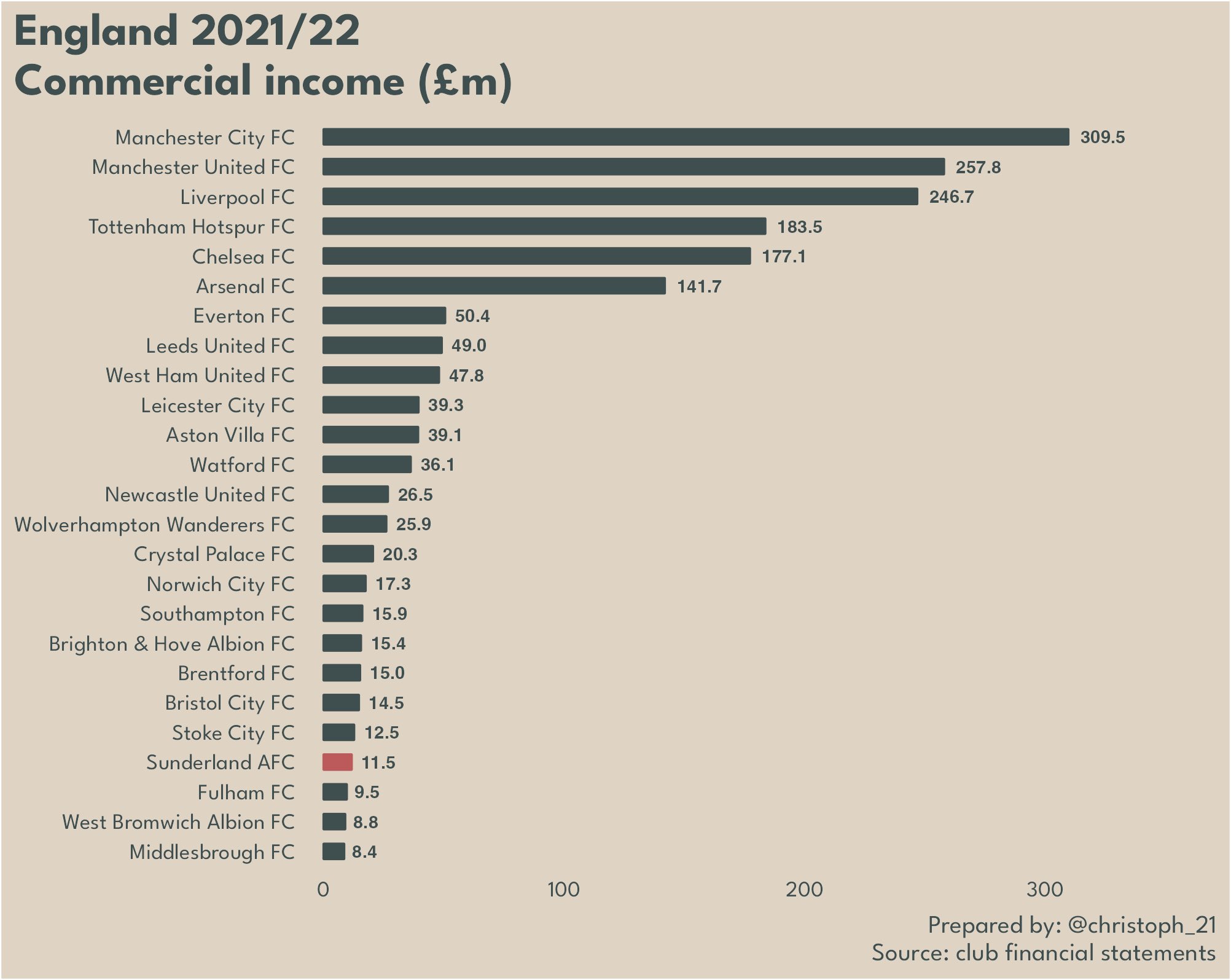

Somewhat surprisingly given shoddy operations that have frustrated many fans in the last two years, Sunderland’s commercial income shot up too, to £11.5m.

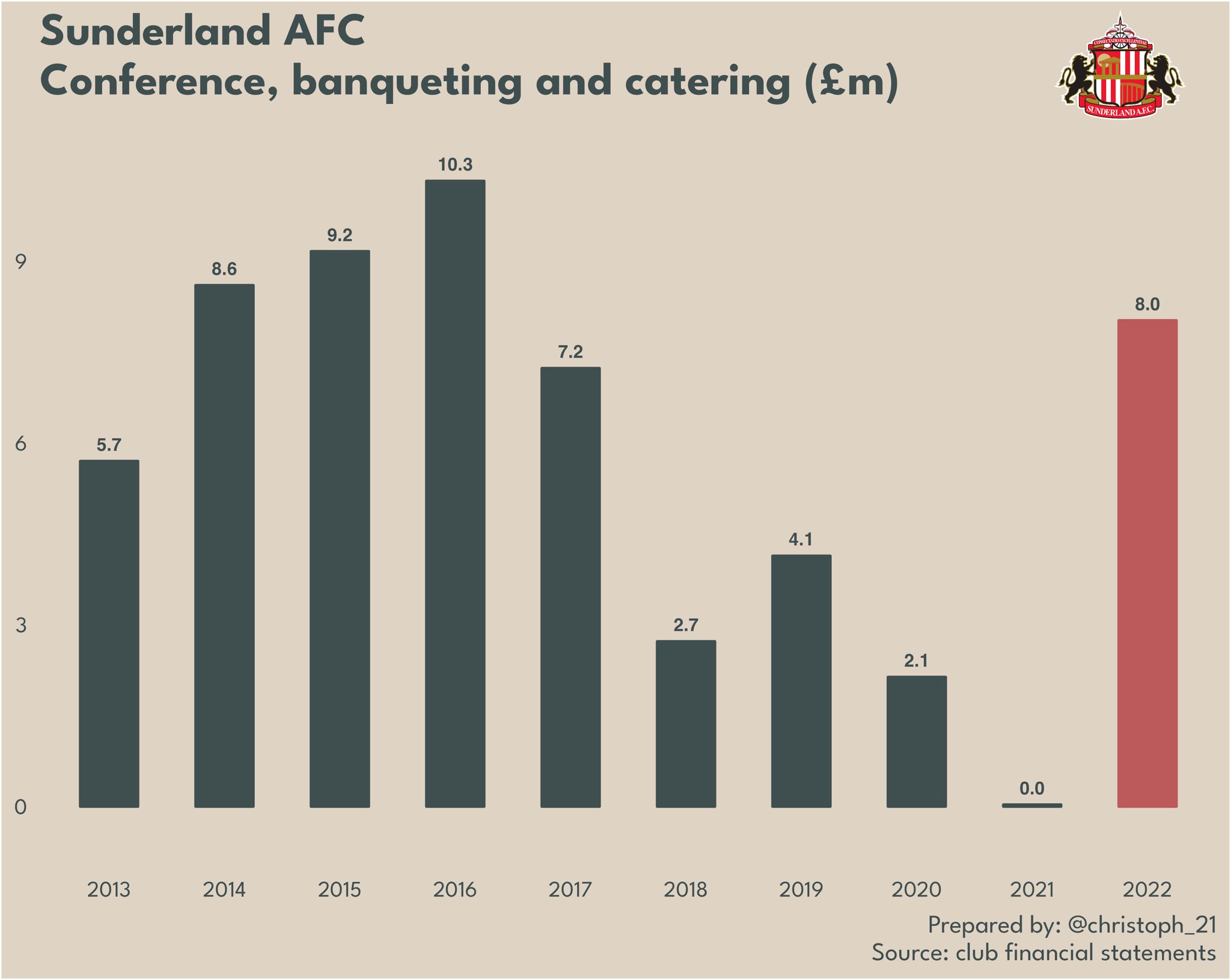

This was mainly due to £8m of conference, banqueting and catering income, which was again a higher figure than the club reported in its final EPL season.

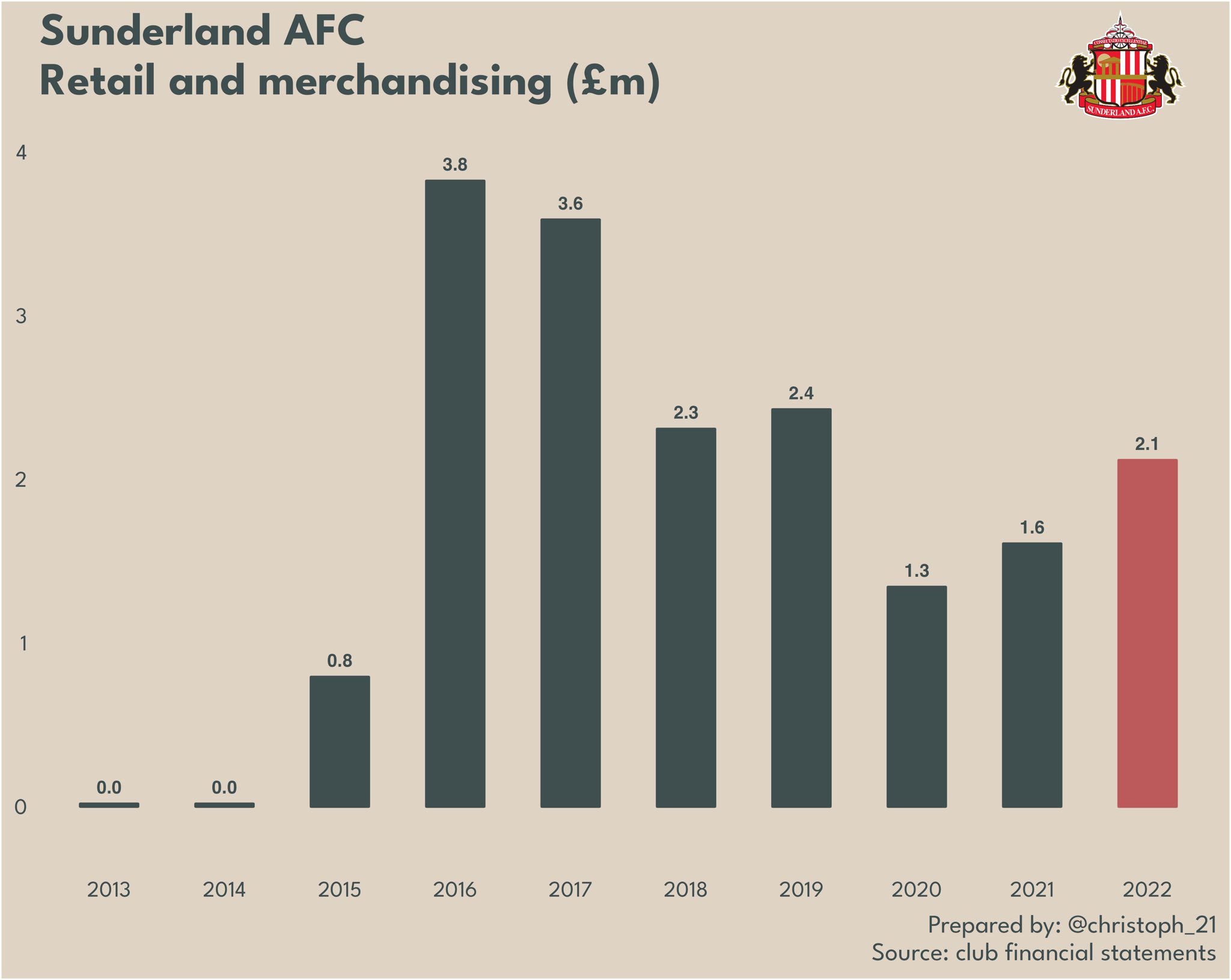

Other elements of commercial income were more in line with supporters’ lived experiences. Retail and merchandising improved by around a third, but was still lower than it had been in 2019, in no small part due to the limited opening hours offered by the club shop across the 2021/22 season.

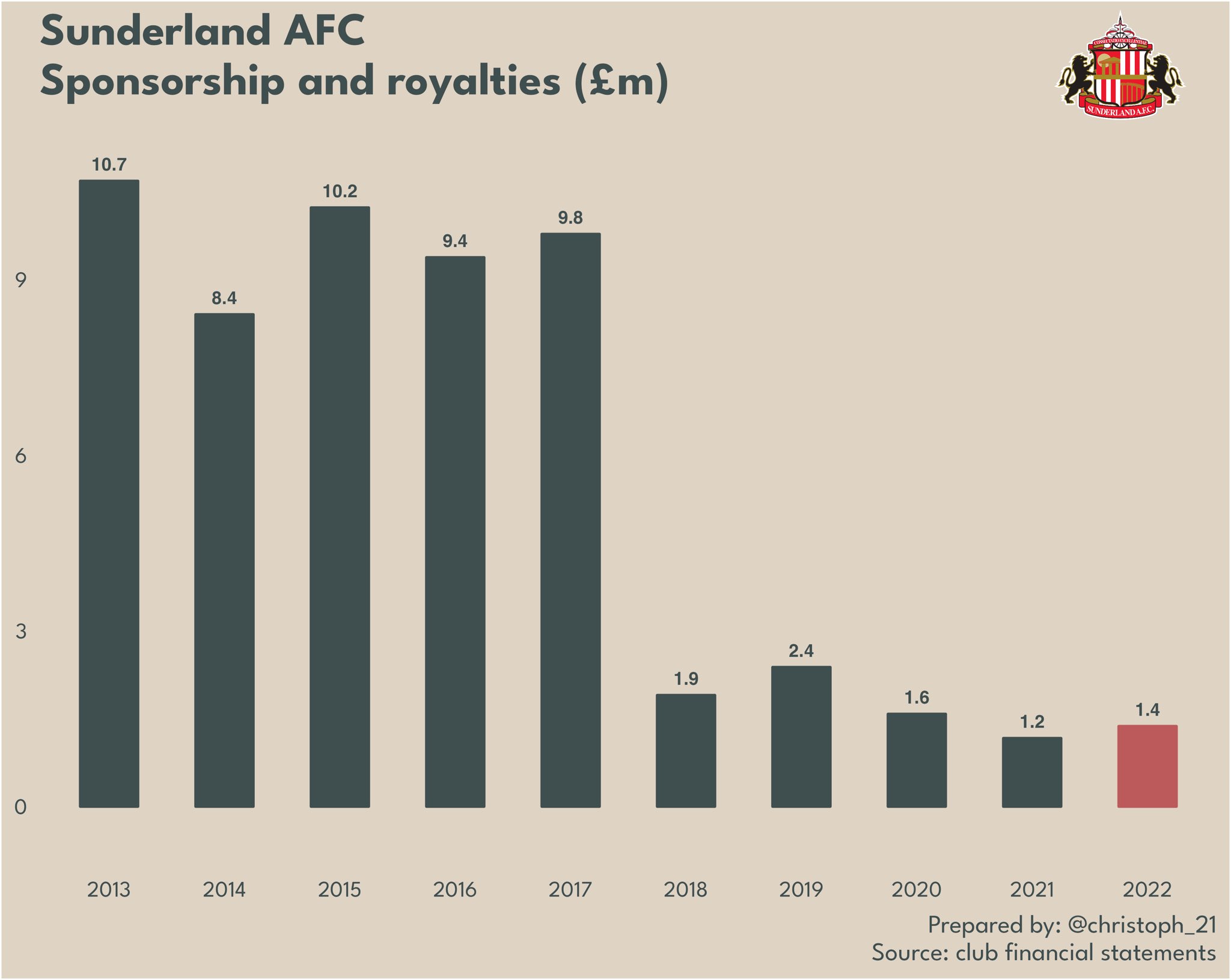

Meanwhile, sponsorship and royalty income barely budged, as the club continued with Great Annual Savings Group (GAS) as its principal shirt sponsor for a second year. The club’s tumble out of the EPL is especially pronounced here, with sponsorship deals falling off a cliff subsequent to relegation in 2017. GAS were replaced by Spreadex for the current and following two seasons.

Again, Sunderland topped the revenue table for commercial income, recording more than double second-placed Ipswich Town. For all the club has been criticised for its commercial operations, the 2022 figures represent an impressive result for a League One club.

One contributing factor was the return to the Stadium of Light of music concerts, as Ed Sheeran and Elton John played a combined three nights at the venue in June 2022. The club noted in the accounts this brought in ‘substantial revenue’ and ‘marks the start of the strategy to secure significant revenue from sources outside of football which mitigates the financial risk related to football performance.’

Sunderland’s commercial income was the 22nd-highest in England in 2022, again meaning the club outperformed most sides in the division above. Still, there’s plenty of room for improvement, particularly in retail, and this should be a focus area for the club going forward.

Indeed, disclosures in the accounts say it will be exactly that. Within the club’s Strategic Report, it was stated that the club is, in future seasons, ‘aiming to increase the contribution from commercial activities to allow greater investment in on-field playing success.’

Wages and other expenditure

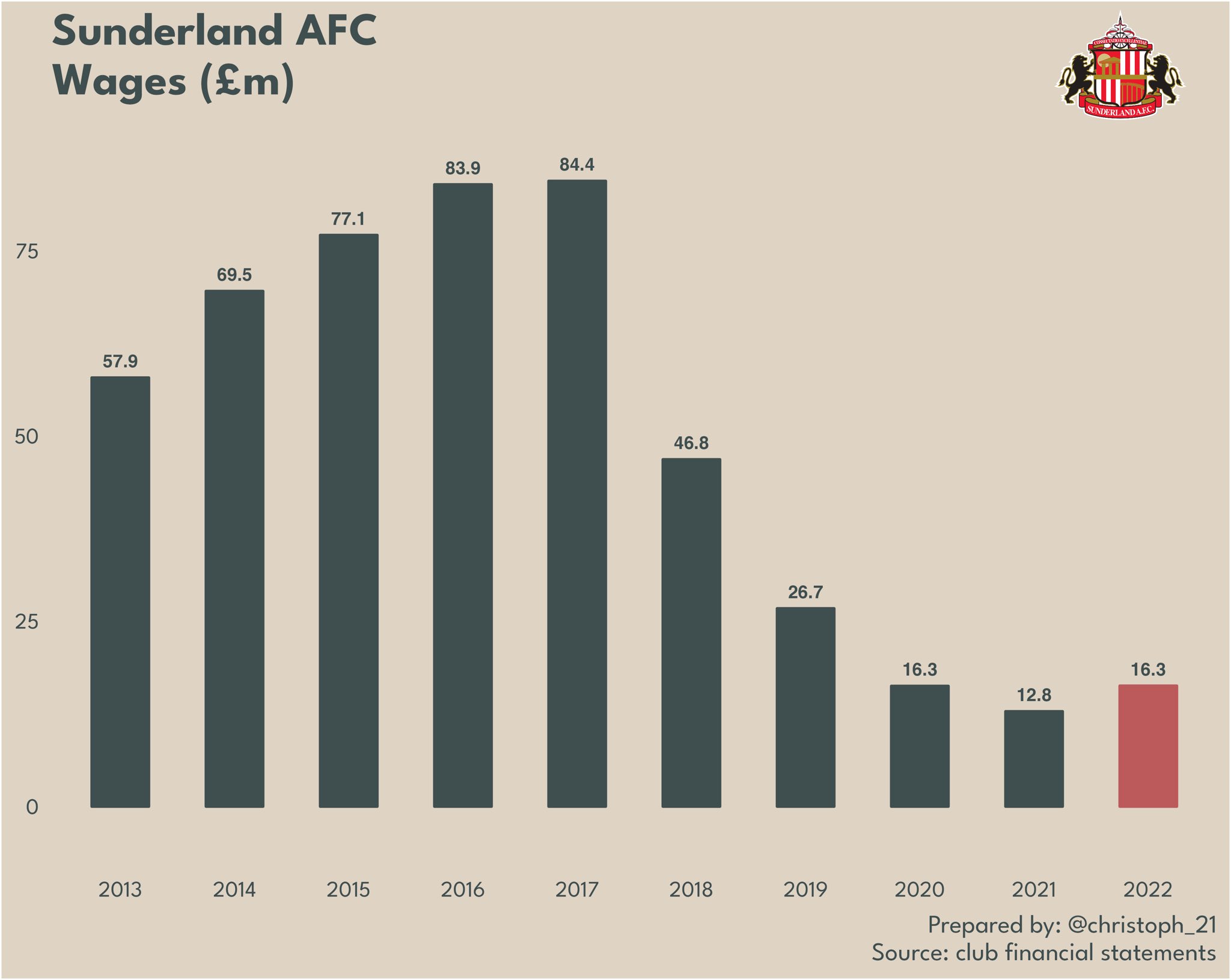

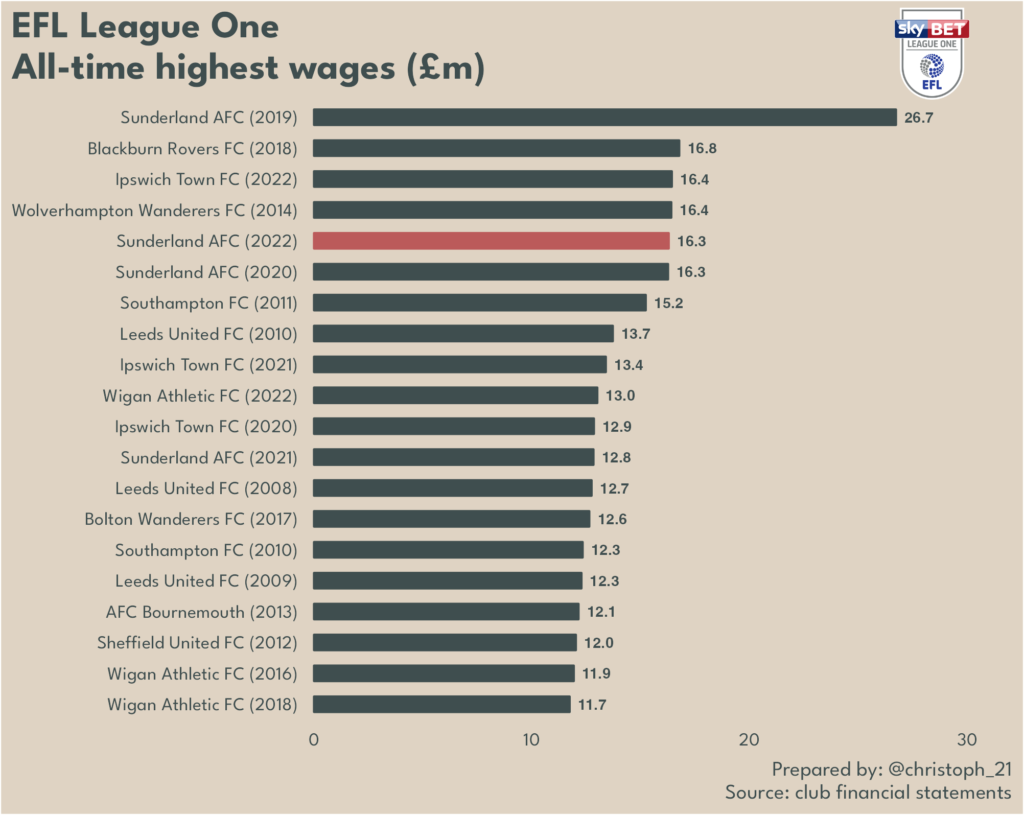

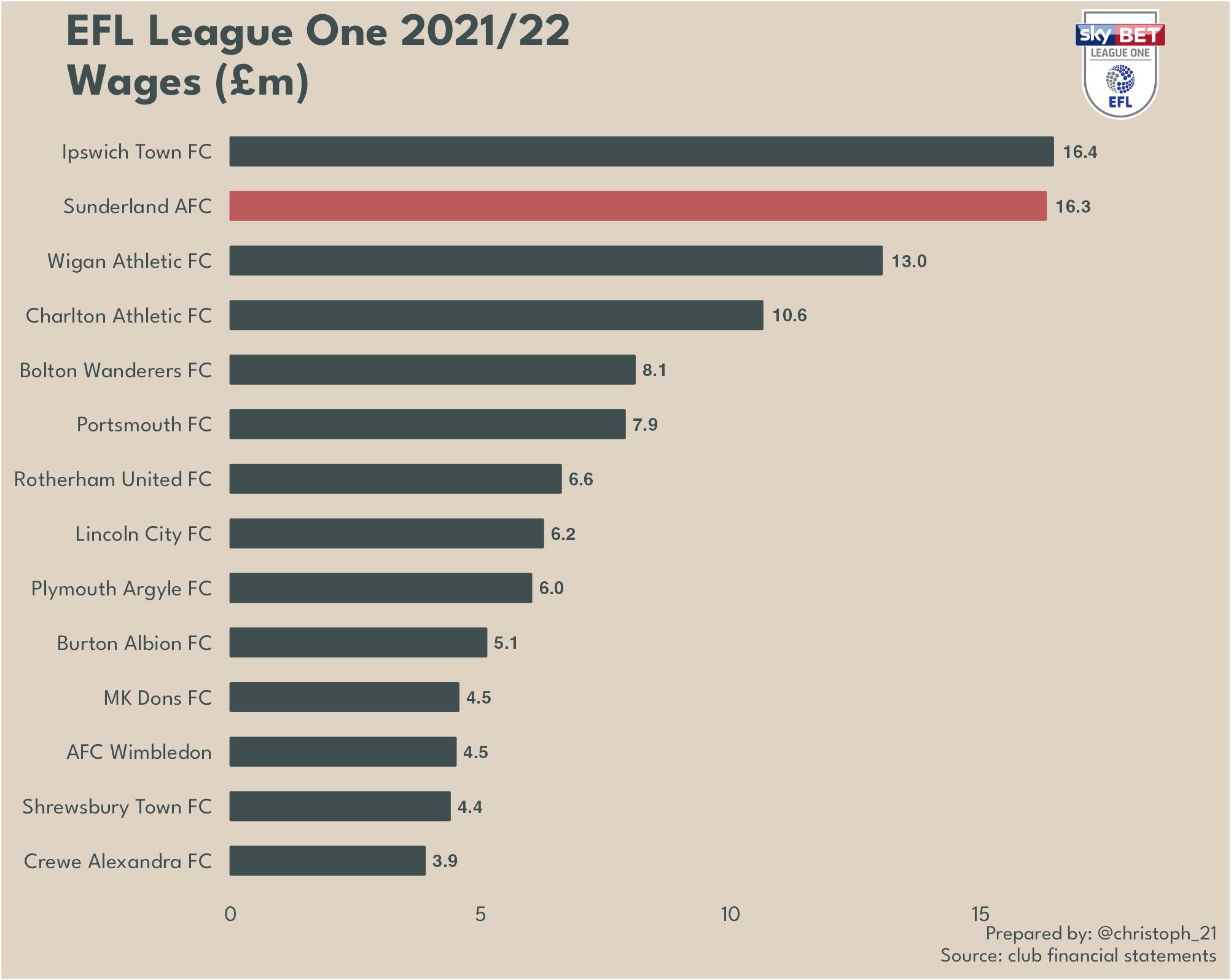

Moving away from income and onto costs, Sunderland’s wage bill increased for the first time in five years, up 27% to £16.3m. Whether any promotion bonuses were paid isn’t disclosed, but that figure is one of the highest ever League One wage bills.

In fact, if we exclude the huge £26.7m expended by Sunderland in 2018/19, a year in which several players remained on the payroll from the club’s Premier League days, last season’s wage bill was just £0.5m behind Blackburn Rovers’ second-highest all-time League One wage bill.

That might seem a little perplexing given the club’s new recruitment strategy and the clear focus on reducing excess costs and not paying players over the odds. A mitigating and important factor to consider is the size of the club and its operations; an unknown chunk of the £16.3m wage bill went on non-playing staff.

Figures disclosed in the accounts state player salaries for 2022 comprised just 34.6% of revenue, down from 68.4% in 2021. That would mean the player wage bill was £9.0m in 2022, up from £7.3m in 2021. It would also mean the club’s non-player salary costs were £7.3m and £5.5m in 2022 and 2021 respectively.

Unfortunately, there’s not a whole lot of clarity on what exactly those percentages cover (are standard playing bonuses included? Were any promotion bonuses paid?), so there’s not too much we can really glean from them, but at the very least it’s worth highlighting Sunderland’s £16.3m wage bill covers a lot more staff than the salary costs of many other League One sides.

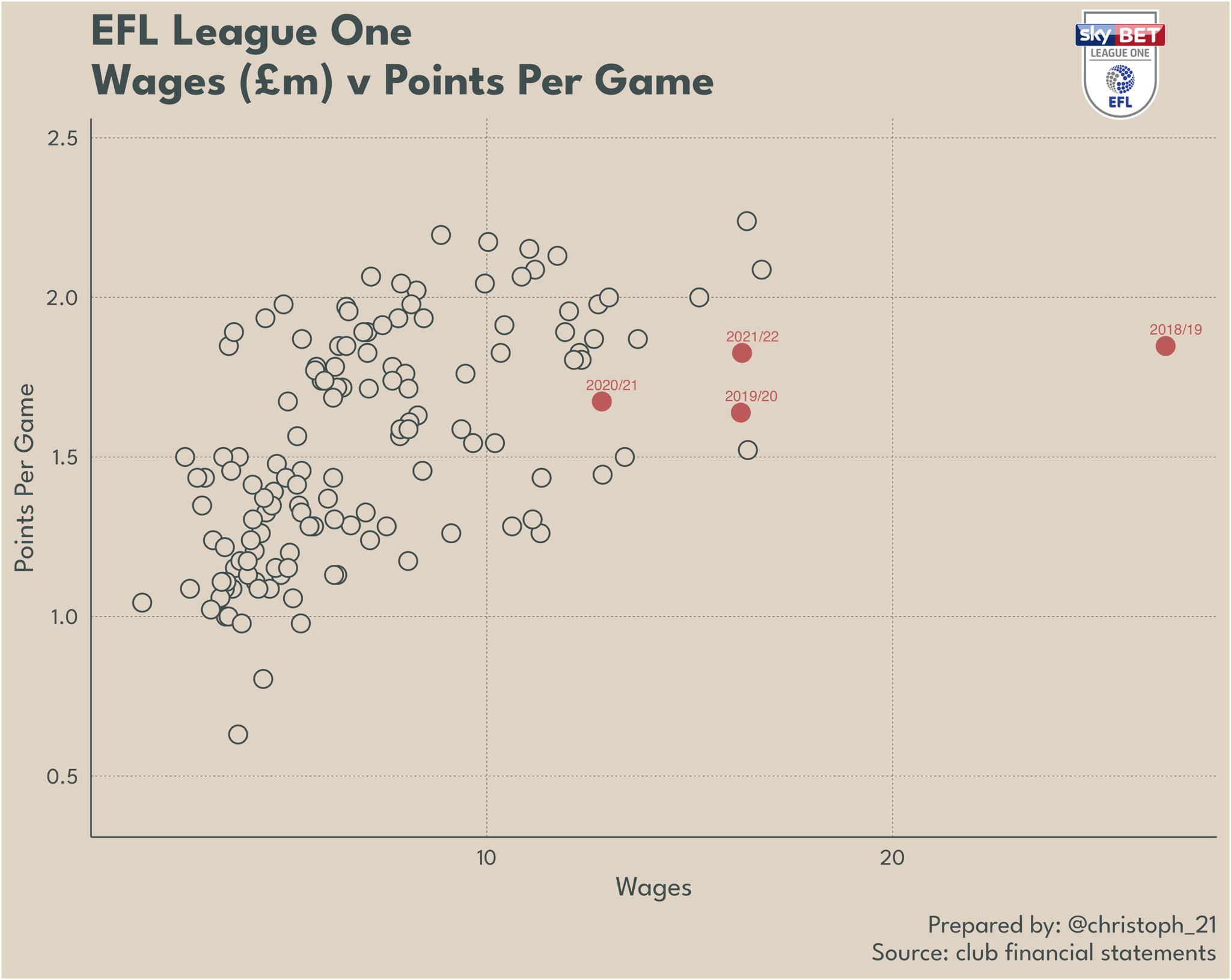

Wages generally dictate how a side will perform, though Sunderland have frequently bucked the trend (for the worse) in the past. Plotting the club’s four League One wage bills against all other clubs since 2012 shows Sunderland as continually high payers – but it did ultimately get them promoted.

Even in spite of all the above, Sunderland’s wage bill wasn’t the highest in League One last season. That accolade went to Ipswich Town, who stole Sunderland’s bit of spending a fortune and not going up. In fairness, they’ve rectified that now, but it wouldn’t be a surprise to see Ipswich’s wage bill has increased even further in 2023.

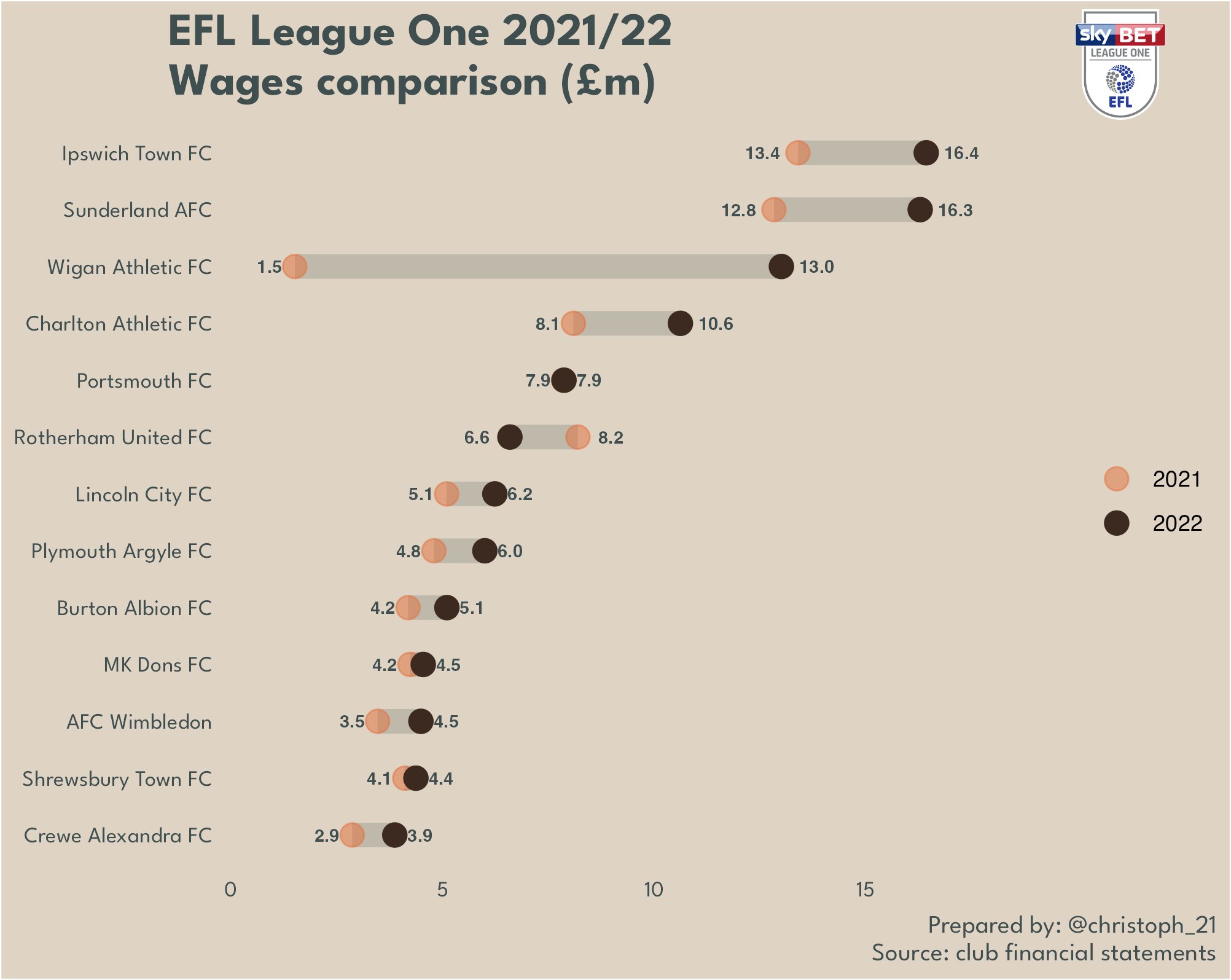

All bar one League One club (Rotherham United, again) increased their wage bill in 2022. For all the pandemic continues to impact club finances, player wages have largely remained resilient throughout the pyramid – and are a primary reason why too many clubs, especially in the Championship, remain in a perilous financial state.

(Note: Wigan Athletic’s 2021 figure only covers from January to June, owing to the club formerly being in administration.)

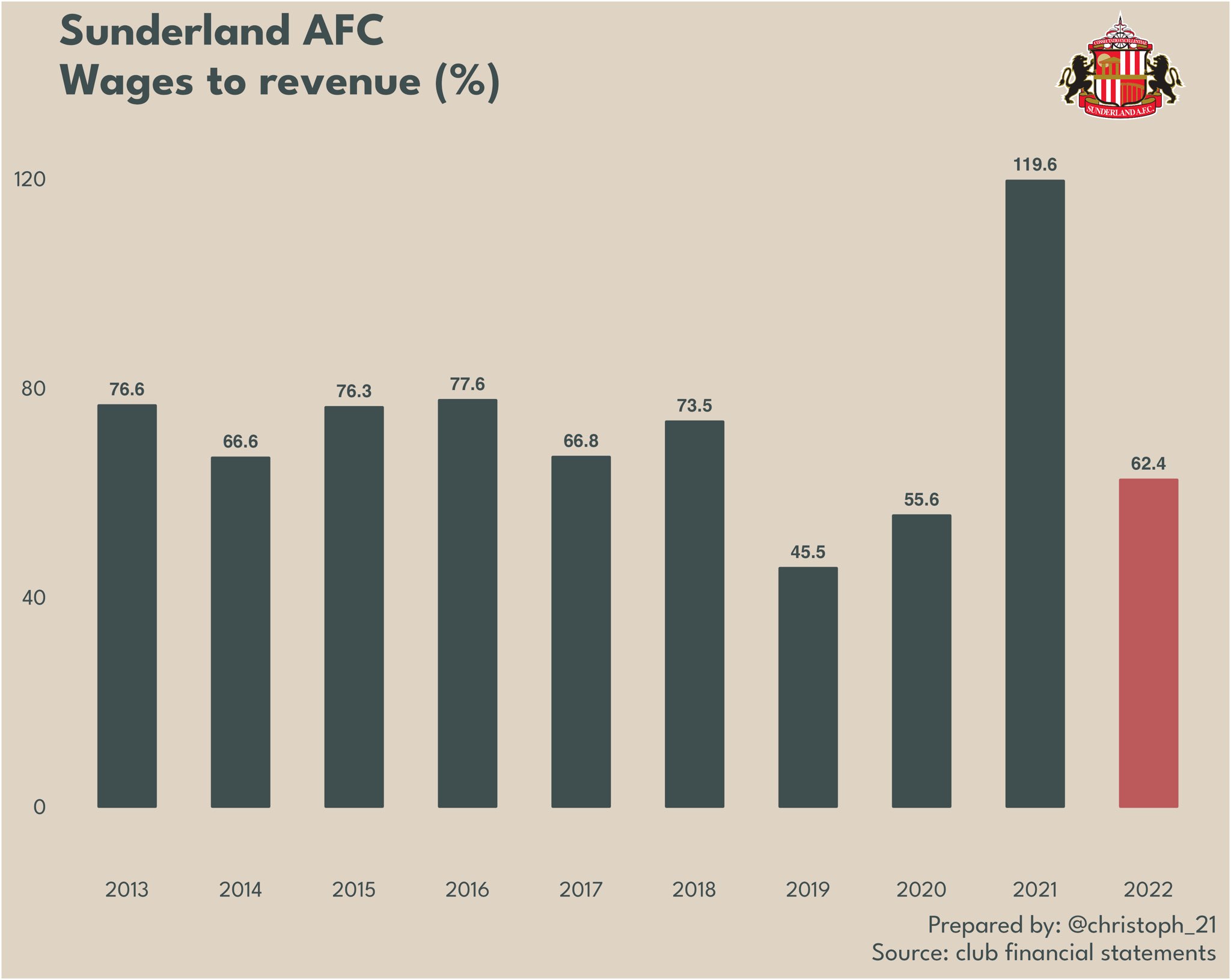

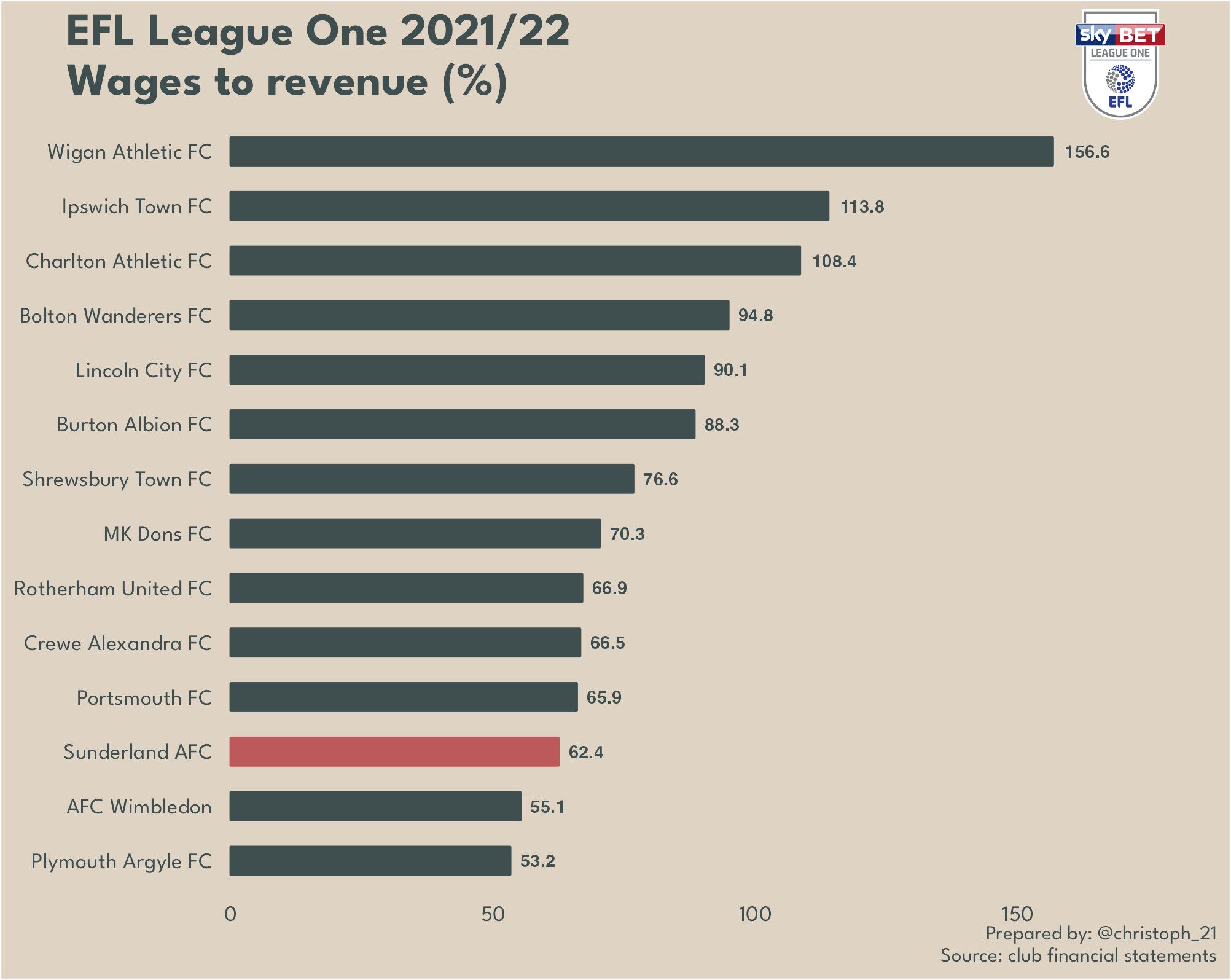

Sunderland’s 27% wage bill growth was comfortably surpassed by the club’s 161% revenue growth and, as a result, the widely-discussed wages to turnover metric fell from 120% (a club record high) to just 62%, well within the range that is generally considered healthy for football clubs.

In fact, excluding two of the three years where the club received parachute payments, and notwithstanding what a chunk of those payments were actually used for, 2022 brought Sunderland’s lowest wages to turnover in the last decade.

What’s more, the club’s wages to turnover ratio was the third lowest in League One, and a far cry from the whopping 157% recorded by fellow promoted side Wigan Athletic.

League One ratios are generally much lower than the madcap figures seen in the Championship where, of the 19 clubs to publish 2021/22 financial results, 14 posted wage bills in excess of an entire year’s income (exclusive of player sales).

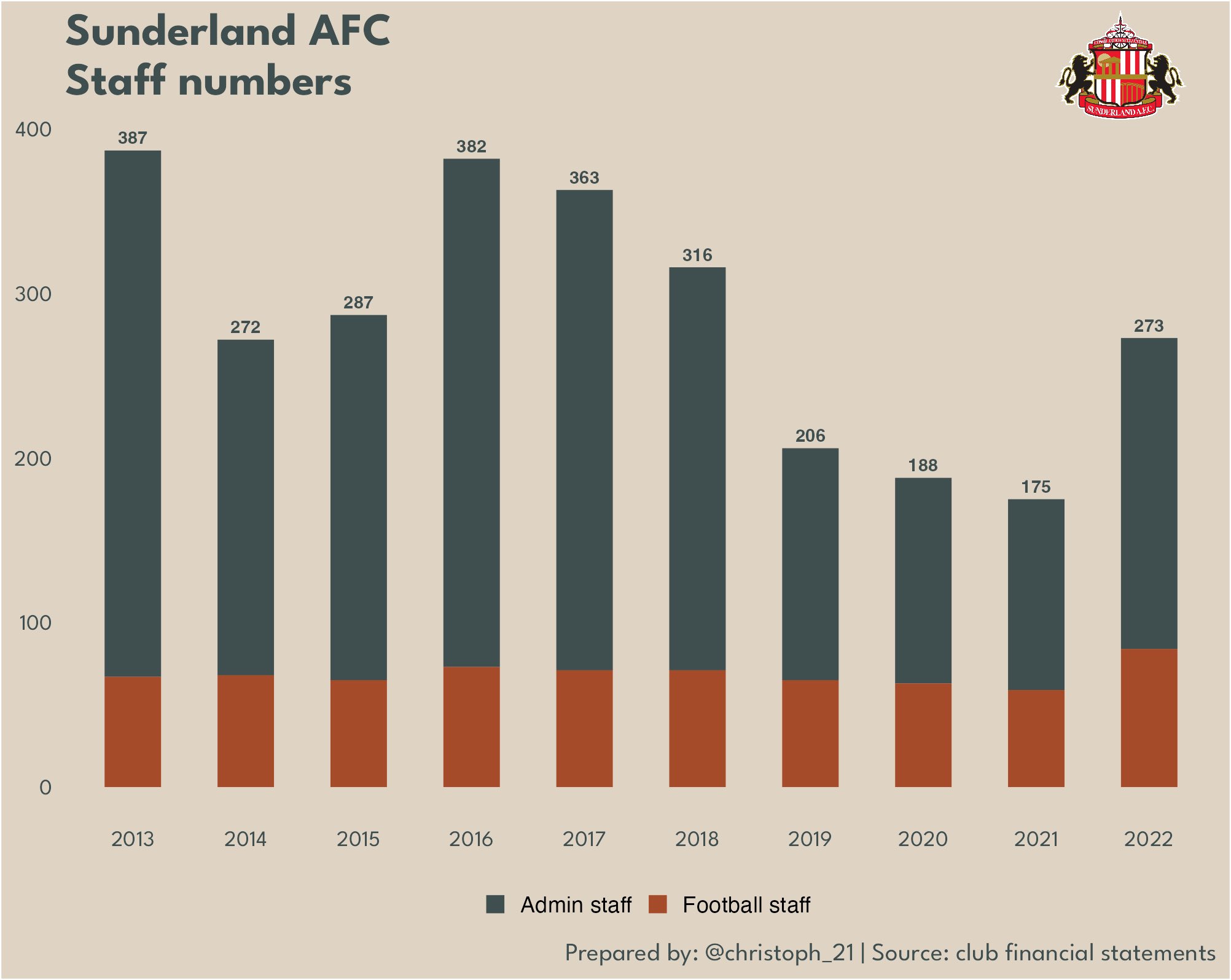

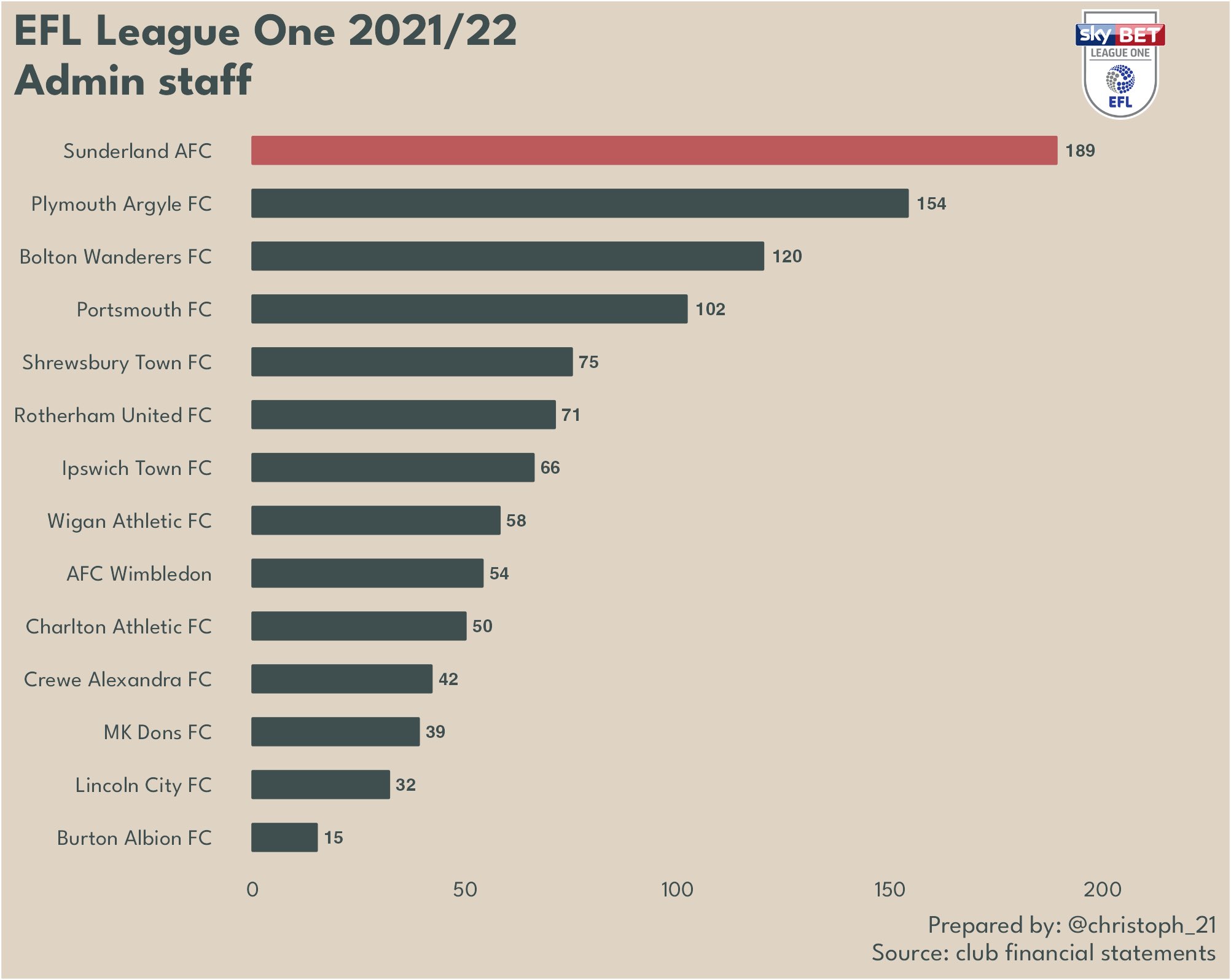

Linked to what was discussed earlier, after years of slashing costs, Sunderland’s core staff numbers (excluding matchday workers) increased by over 50%. The number of football staff at the club leapt 42%, to 84, reflective the increased investment there and the filling of key areas left woefully understaffed during the Madrox days.

Sunderland also employed more administrative staff than any other League One club, again reflecting the size of the club and its operations. The average number of matchday staff jumped too, up to 320. That’s a significant increase on the 157 employed in 2018/19 (the last full season before the Covid-19 pandemic hit), and again indicates just how much the club was pared to the bone under its former ownership group.

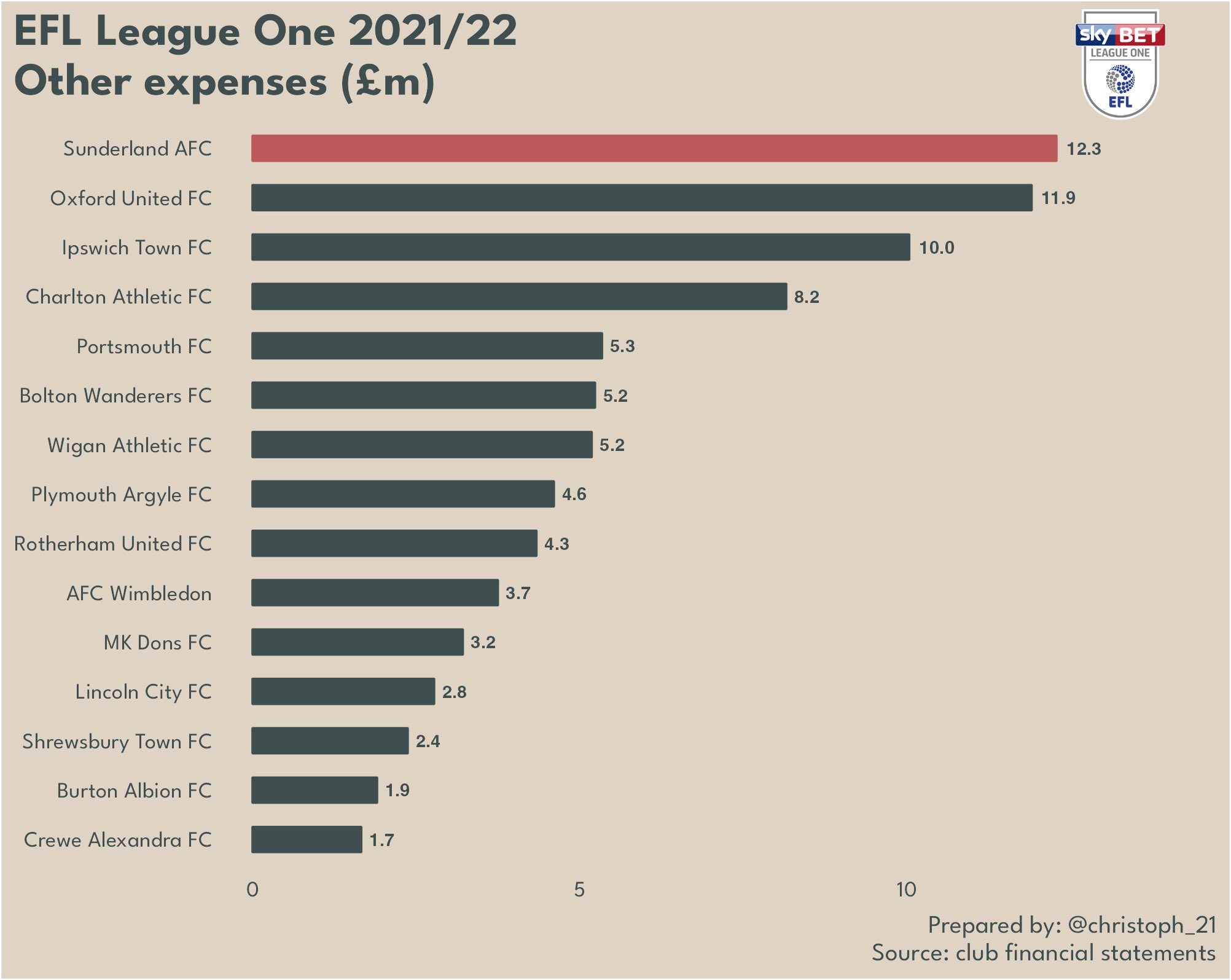

Just as wages grew, so did Sunderland’s more general expenses. Having fallen while games were played out in empty stadia, club costs rose back toward pre-pandemic levels, not helped by increased energy prices.

The club also said it spent notable amounts on essential infrastructure repairs, ones which didn’t meet the criteria to be considered capital costs (i.e. they were routine costs that kept assets in their original condition, rather than improvements that increased asset values).

This explains why the accounts state the club spent £1.3m on investment in the stadium and academy in the year (and £1.7m the year prior), but the capital expenditure figure was less than half that, as detailed later in this piece. Again, this reflects the costs of just keeping the lights on at the club, and why it is unlikely to ever be truly sustainable outside the top tier of English football.

Sunderland’s other expenses were, correspondingly, the highest in the division. That said, the gap to others wasn’t huge, and it should be remembered the club often ran a skeleton operation during 2021/22. In other words, had the club’s off-field operations been ran to the standard many fans expect, expenses and losses would have been greater than they were.

Player trading

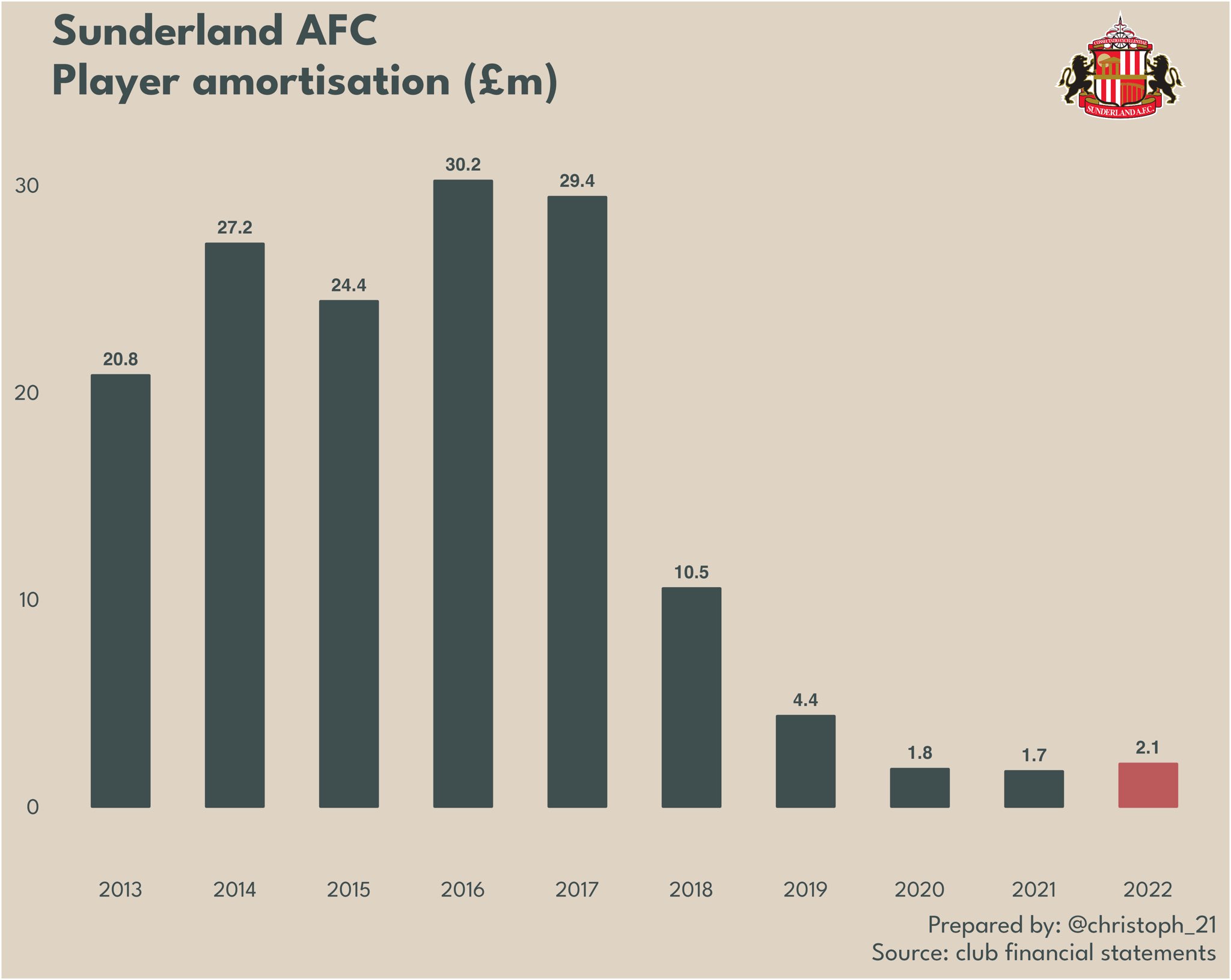

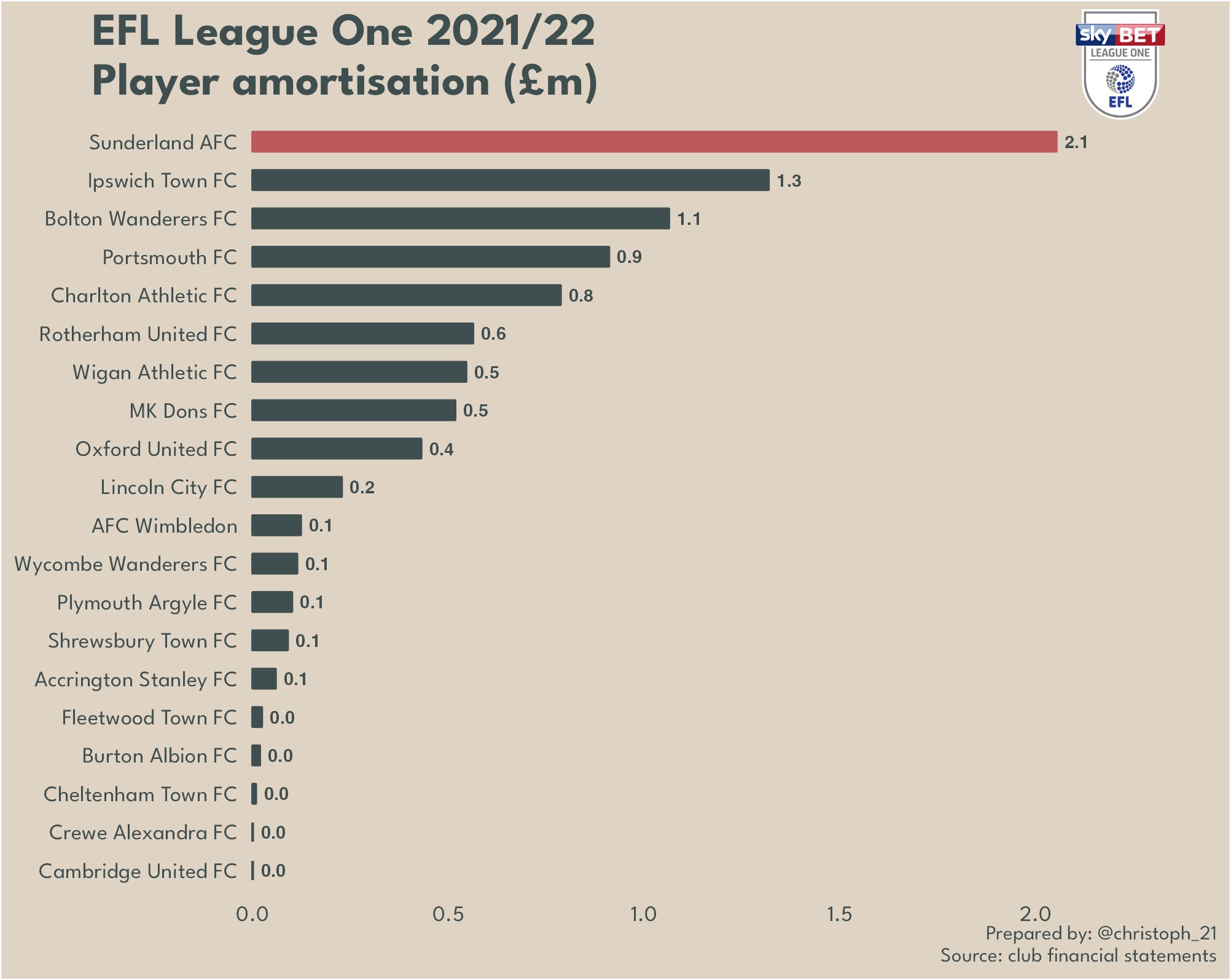

Sunderland’s player amortisation – player transfer fees, spread across the life of the player’s contract – rose to over £2m. This was a small (£0.4m) increase on a year earlier, reflecting the club’s return to investing in the playing squad.

That £2m was the highest player amortisation in League One, a division in which clubs spend little on transfer fees. Sunderland’s figure isn’t fully reflective of current playing squad though, as it also included an estimated £0.8m relating to Will Gregg, whose disastrous stay on Wearside officially ended in June 2022.

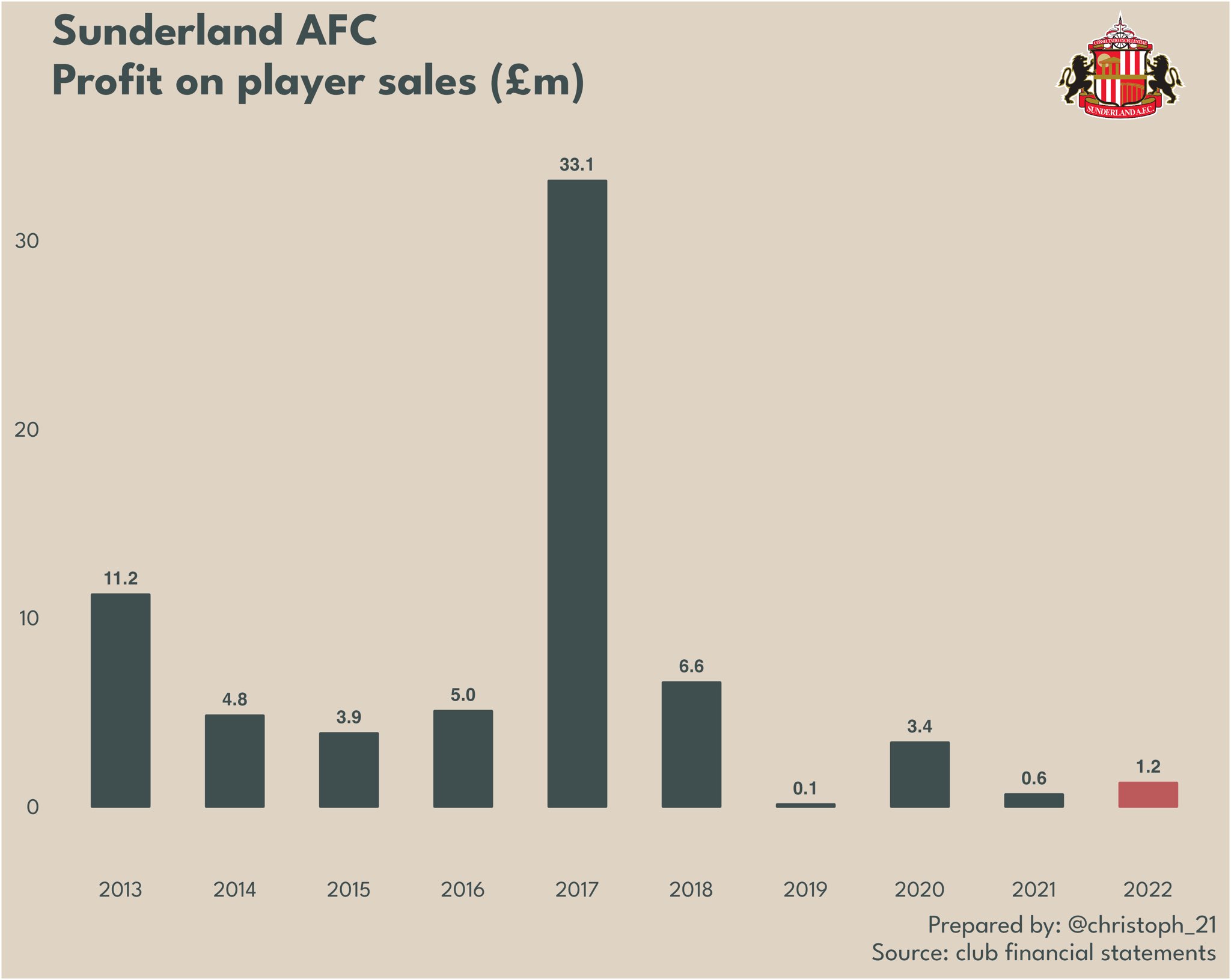

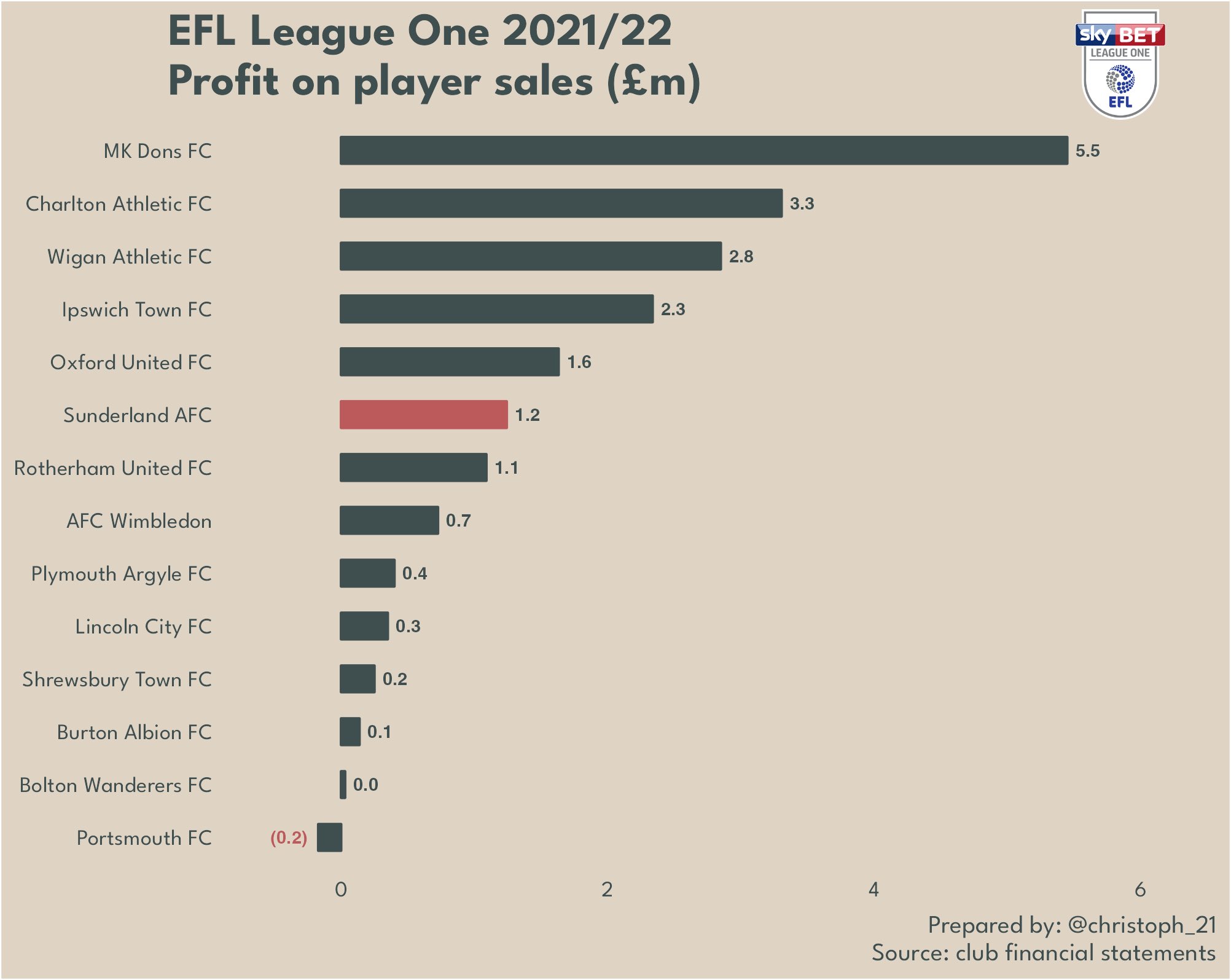

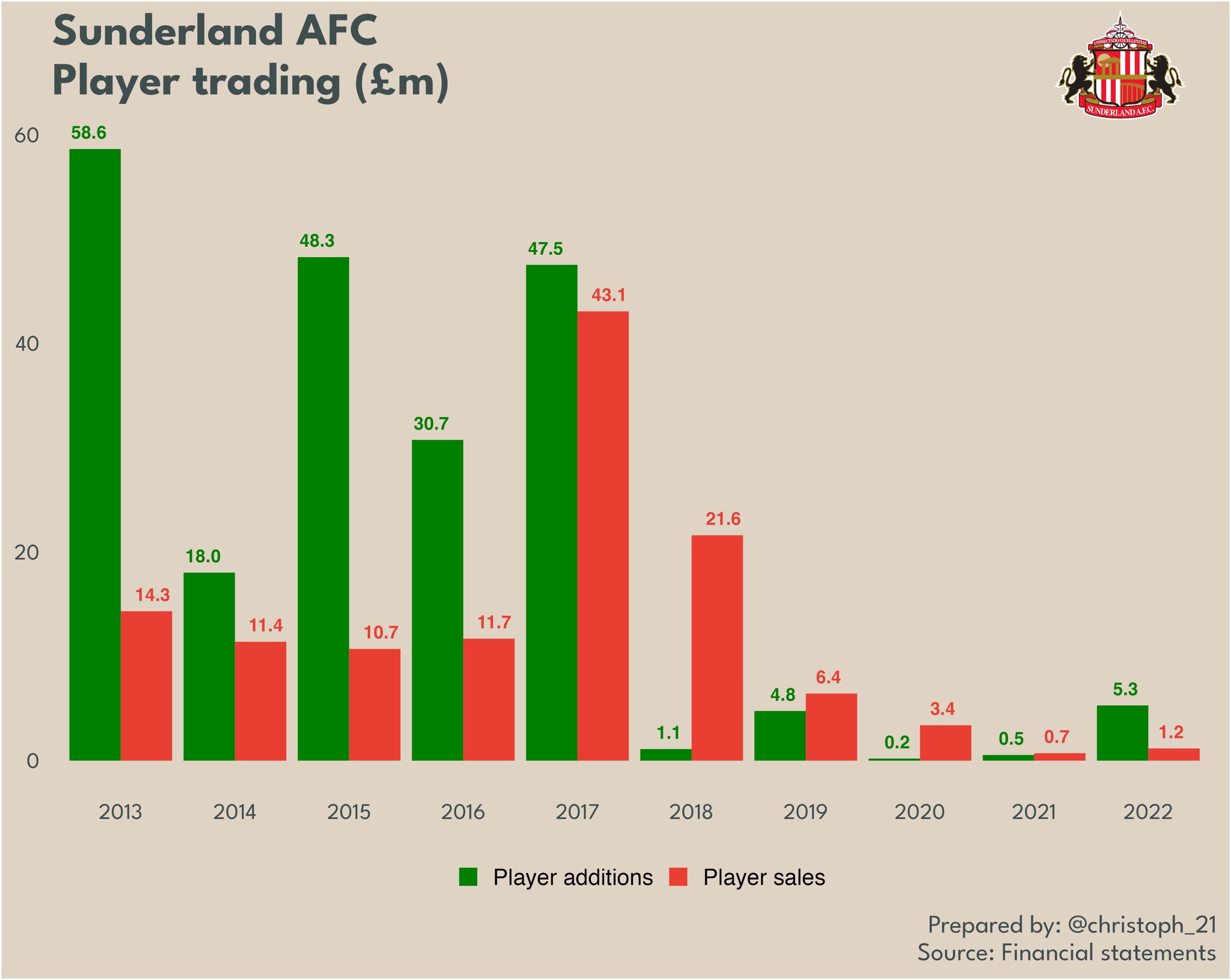

Sunderland are historically poor at making profits on players, with Jordan Pickford’s £30m transfer to Everton in 2017 a clear outlier. The club made a profit of £1.2m on selling the likes of Denver Hume, Benji Kimpioka and academy product Francis Okoronkwo – plus any add-ons that crystallised in the year from past sales.

Even in League One, the club’s player sale profits were little better than middling, reflecting the lack of assets in the playing squad. Sunderland’s dearth of income here is a primary reason behind the significant shift in transfer policy seen since February 2021, as the club seeks to supplement day-to-day revenues with significant player sales income, a strategy most successfully enacted by Brentford in recent years.

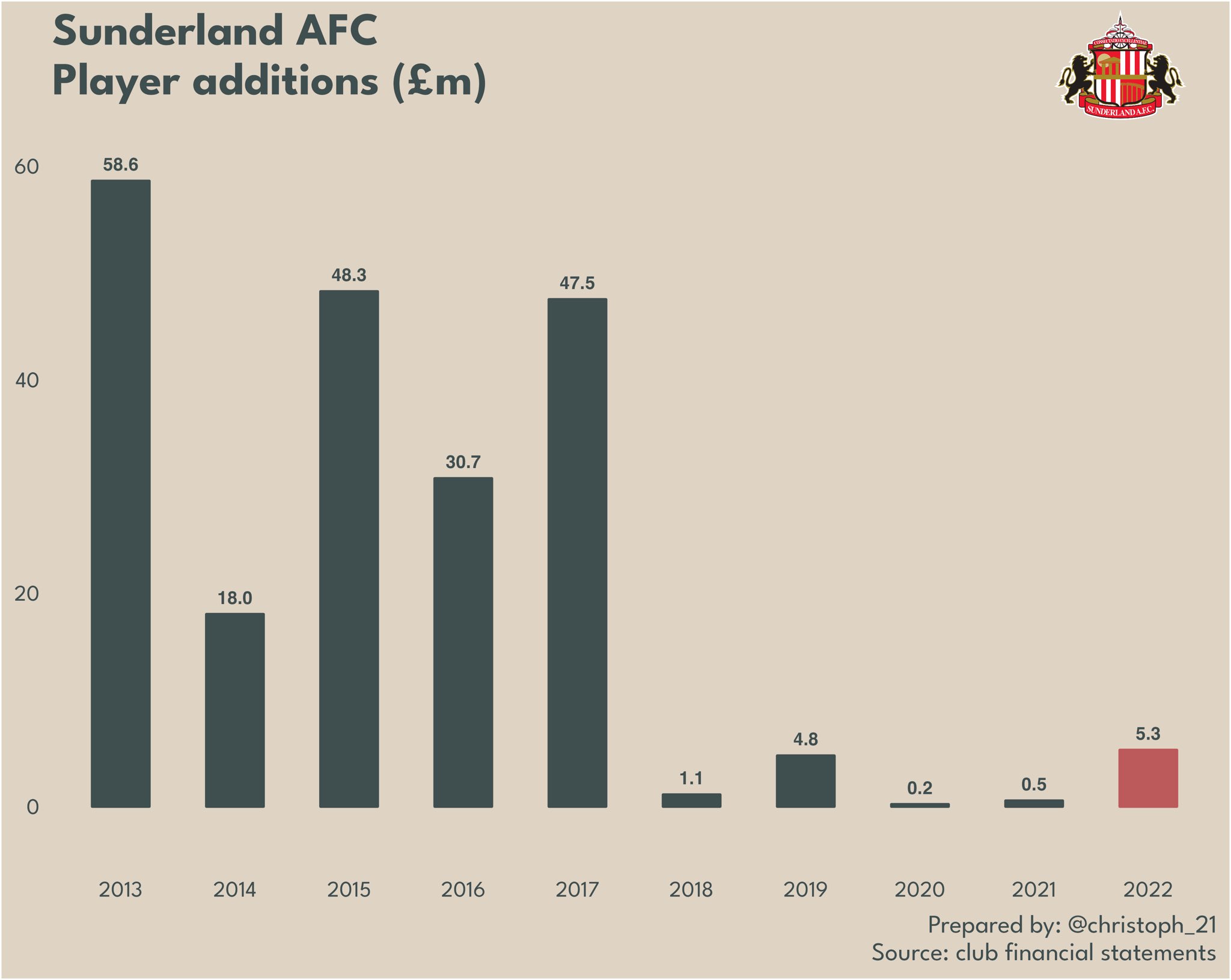

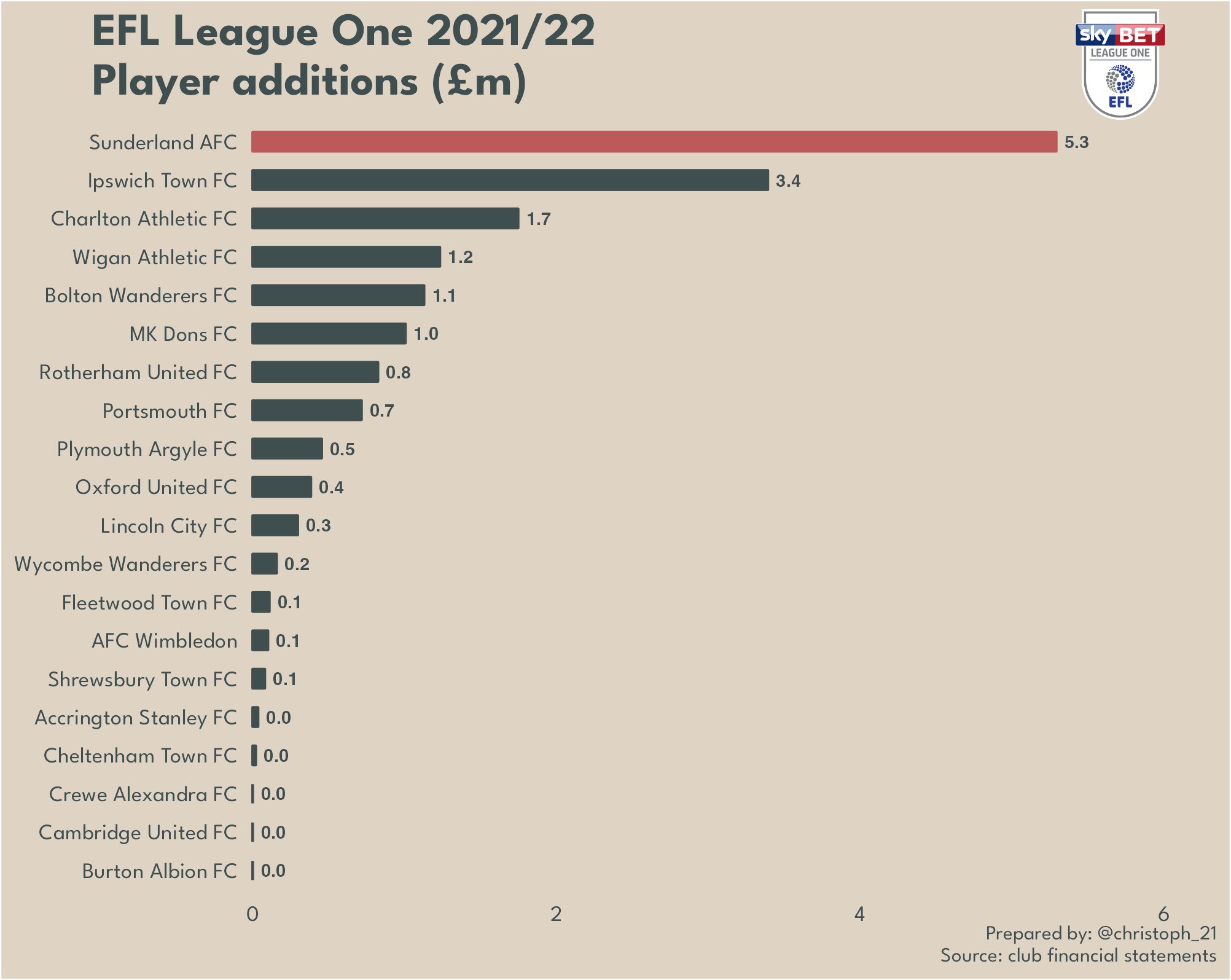

On the incoming side of things, Sunderland player additions of £5.3m were the highest single-year outlay from the club since EPL relegation. Due to when the company’s accounting year end falls, this figure includes amounts spent in the last summer transfer window, as the club readied itself for the Championship.

Consequently, Sunderland had the highest spend on transfers in League One in 2022. That figure is misleading, as much of the spend is expected to have come after the club had been promoted from the division.

Sunderland’s net spend of £4.1m was positive for the first time since 2017, reflecting the need to invest in the playing squad ahead of a season in the Championship, as well as whatever outlay the club made on the smattering of players signed for fees in August 2021.

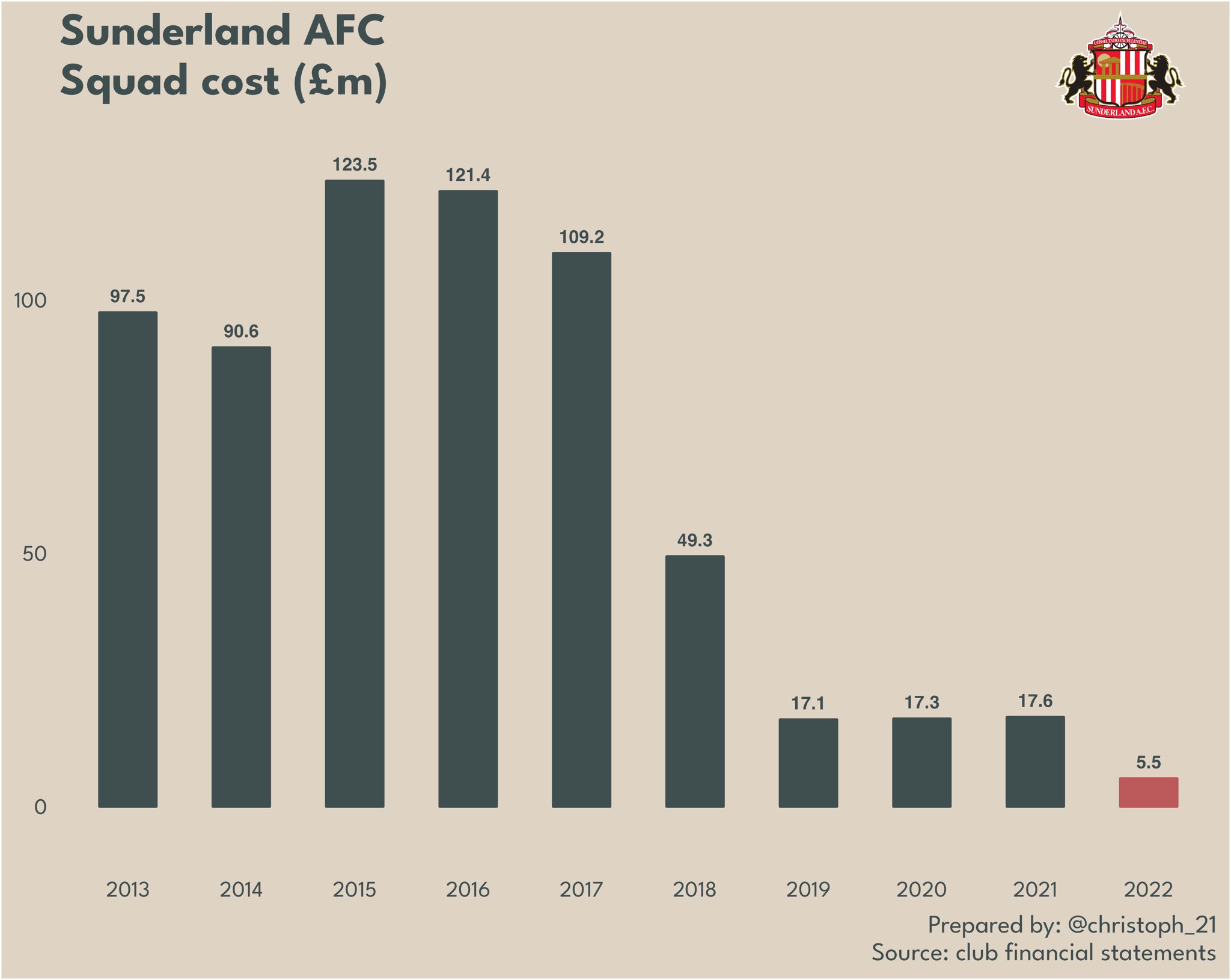

Sunderland’s squad cost – the total amount of fees spent on the current playing squad over the years, inclusive of agent fees and signing-on fees – actually fell due to the amounts paid for Bryan Oviedo and Lee Cattermole dropping away (though the accounting employed here is pretty dubious) as the two were finally fully paid off.

In 2019 the pair were released from the club and their contracts deferred, a decision lauded by some as smart business. In reality, it simply kicked their costs down the road into a period where the club’s income was pre-ordained to fall (due to the disappearance of EPL parachute payments), and became yet another millstone around the club’s neck. With the disappearance of these costs, Sunderland can now finally say they are rid of any financial hangovers from the Ellis Short days.

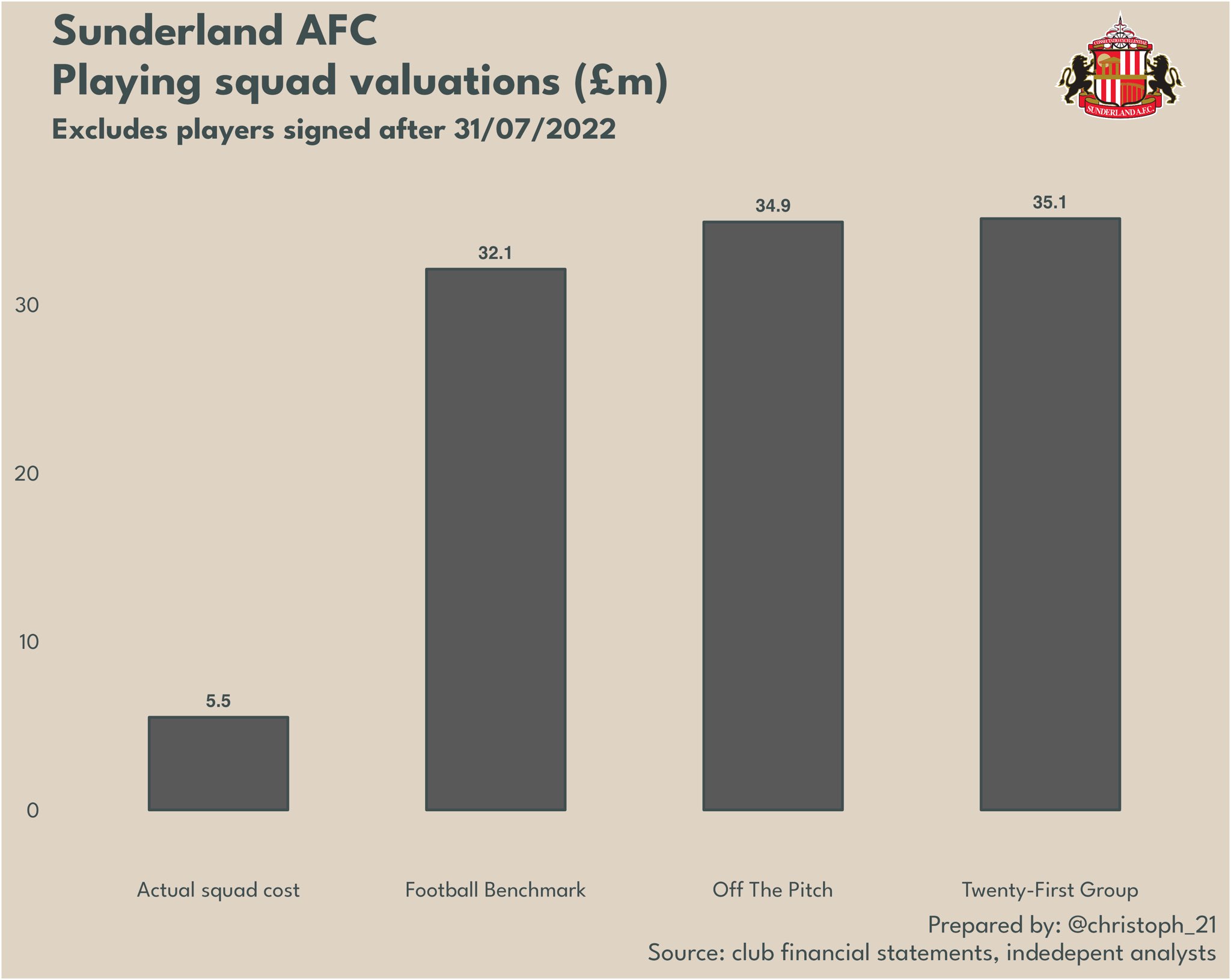

In all, the entirety of Sunderland’s current squad, excluding loanees and players signed post-July 2022 (Abdoullah Ba, Jewison Bennette, Pierre Ekwah, Joe Anderson and Isaac Lihadji) was signed for a total of £5.5m.

Given the club’s new focus on signing players for low amounts and then, at some stage, selling them for a profit, we reached out to a number of football consultancy businesses who utilise and regularly update player valuation software.

Recently calculated data obtained from Football Benchmark, Twenty First Group and Off The Pitch showed that all three currently value Sunderland’s players far higher than their overall cost, with the total market value of the current squad, excluding loanees and post-July 2022 signings, ranging from £32-35m.

Some observers and fans might suggest even those valuations, despite being six to seven times the amount the club paid for its squad, are on the low side. Transfer valuations are an imperfect science, with every transfer having a unique set of circumstances surrounding it, and the valuations obtained are more of a general guide than a definitive figure that will be proven correct.

That said, conversations with the consultancies threw up some explanations for why some player values mightn’t be as high as Sunderland fans may expect. Taking Dan Ballard as an example, the man signed from Arsenal plays in a position that historically doesn’t generate huge fees (Harry Souttar’s recent move from Stoke City to Leicester City being a clear exception) and, more importantly, has played relatively few minutes this season.

Additionally, a growing trend suggests Championship clubs are struggling to earn as much from player sales as might be hoped unless those players have EPL experience to begin with. In 2021/22 only three Championship clubs cleared £20m in incoming transfer fees, and all of them had been recently relegated.

Correspondingly, the Sunderland player most highly valued by each of the three consultancies was Jack Clarke, someone who, though he didn’t play much for Spurs, has been signed by an EPL club before and, on this season’s showing, could very well walk straight into a mid- to lower-table side in the top tier.

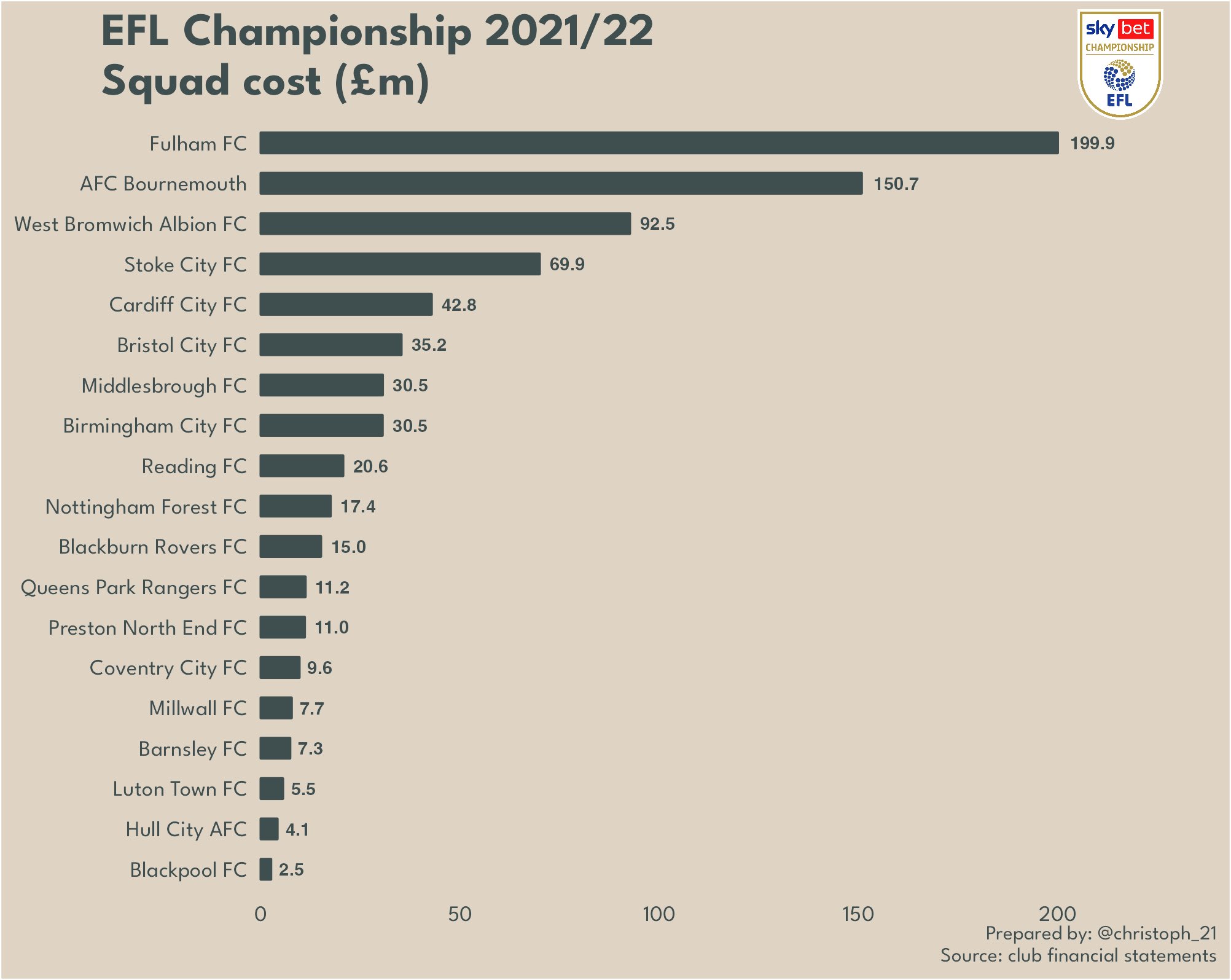

A look at Championship squad costs as at the end of 2021/22 doesn’t allow for perfect comparison given Sunderland’s later reporting date but, even after considering that, the hefty amounts expended by clubs in the division show just how well Sunderland are doing to be competing for a play-off spot this season.

The potential amounts Sunderland may have to pay out in add-ons on players increased five-fold in the year, up to £4.5m. That means that, in total, the current squad could end up costing the club £10m in total fees.

That still seems a pretty impressive amount given the undoubted quality we’ve seen this season, but an important caveat to note is what these accounts don’t tell us. Sunderland are known to have included sell-on clauses in a number of the incoming deals they’ve made since February 2021 and, as there’s no way to quantify the potential impact of those clauses until a player sale is made, no allowance/disclosure is made of them in the financial statements.

Little has been spoken of publicly either, though reliable sources from West Ham United have stated the deals for Ali Alese and Pierre Ekwah each include a clause whereby the Hammers are due 25% of any future sale proceeds Sunderland may make.

Given the low overall spend on the squad, it would be a shock if such clauses weren’t present for other signings too. That’s important and could be crucial to the success of the club’s new recruitment strategy; such clauses inherently limit the profitability of the strategy, and therefore the amounts available to spend on replacing sold players.

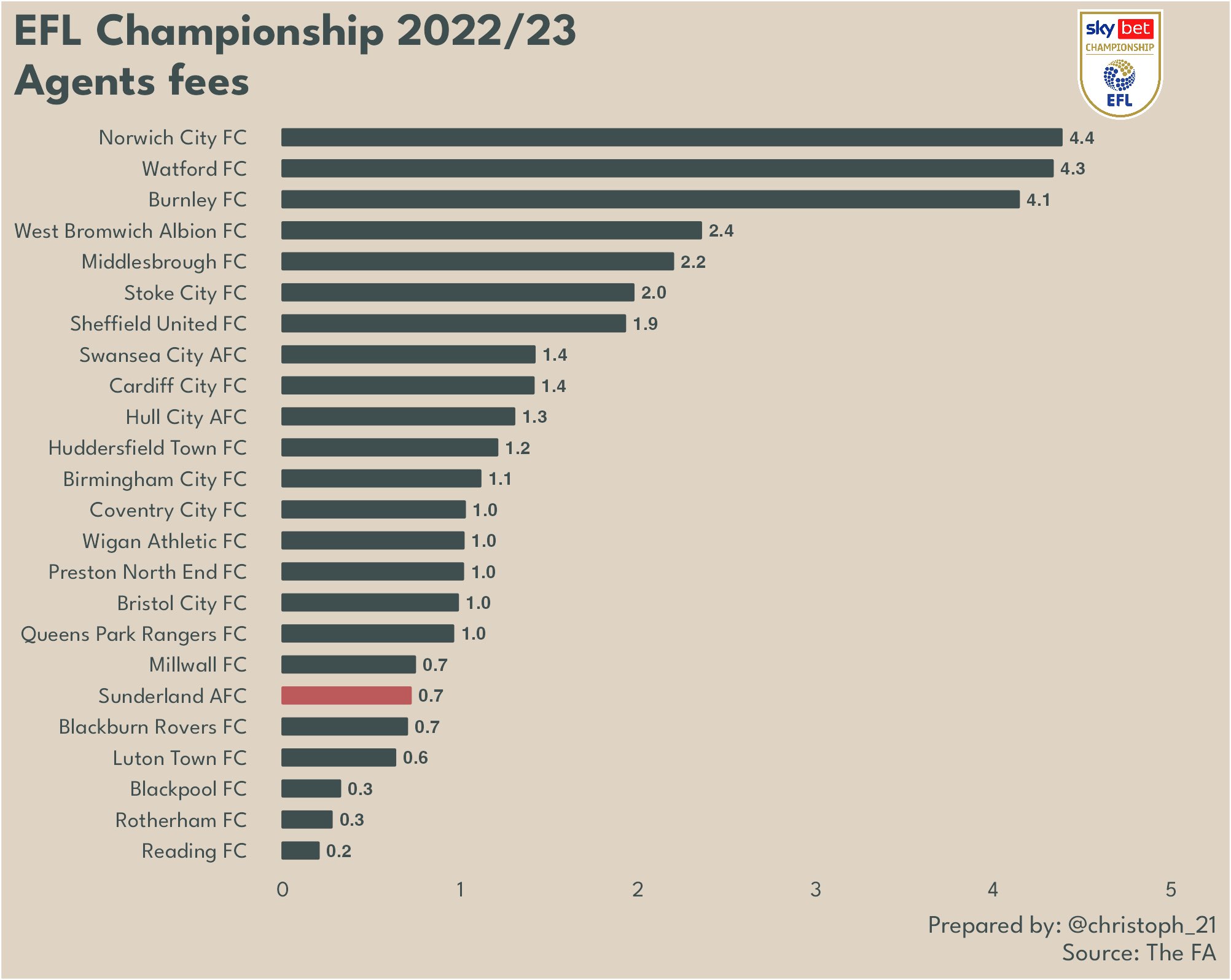

Sunderland’s low transfer spend is further underlined by them having the sixth-lowest spend on agent fees in this season’s Championship.

Infrastructure

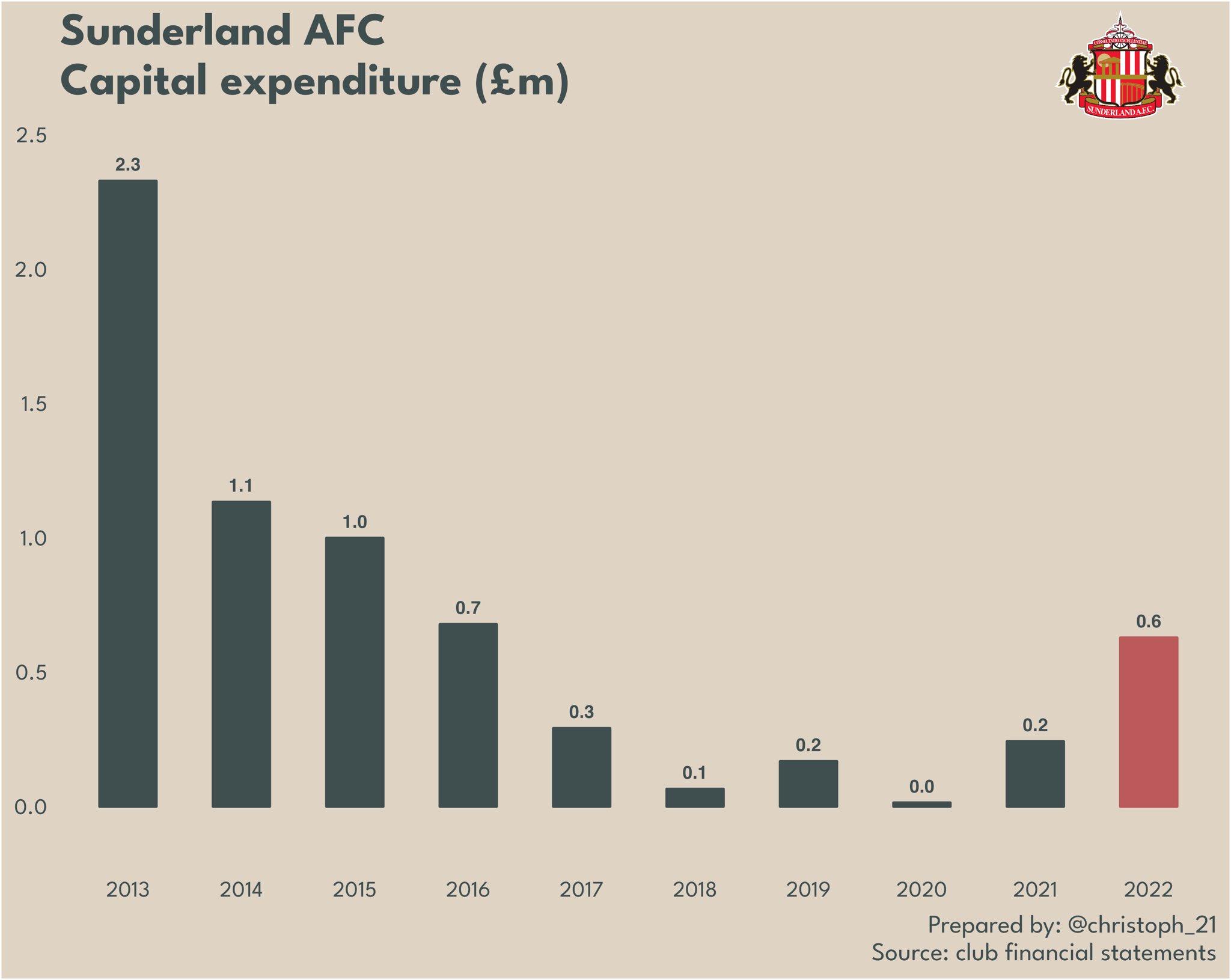

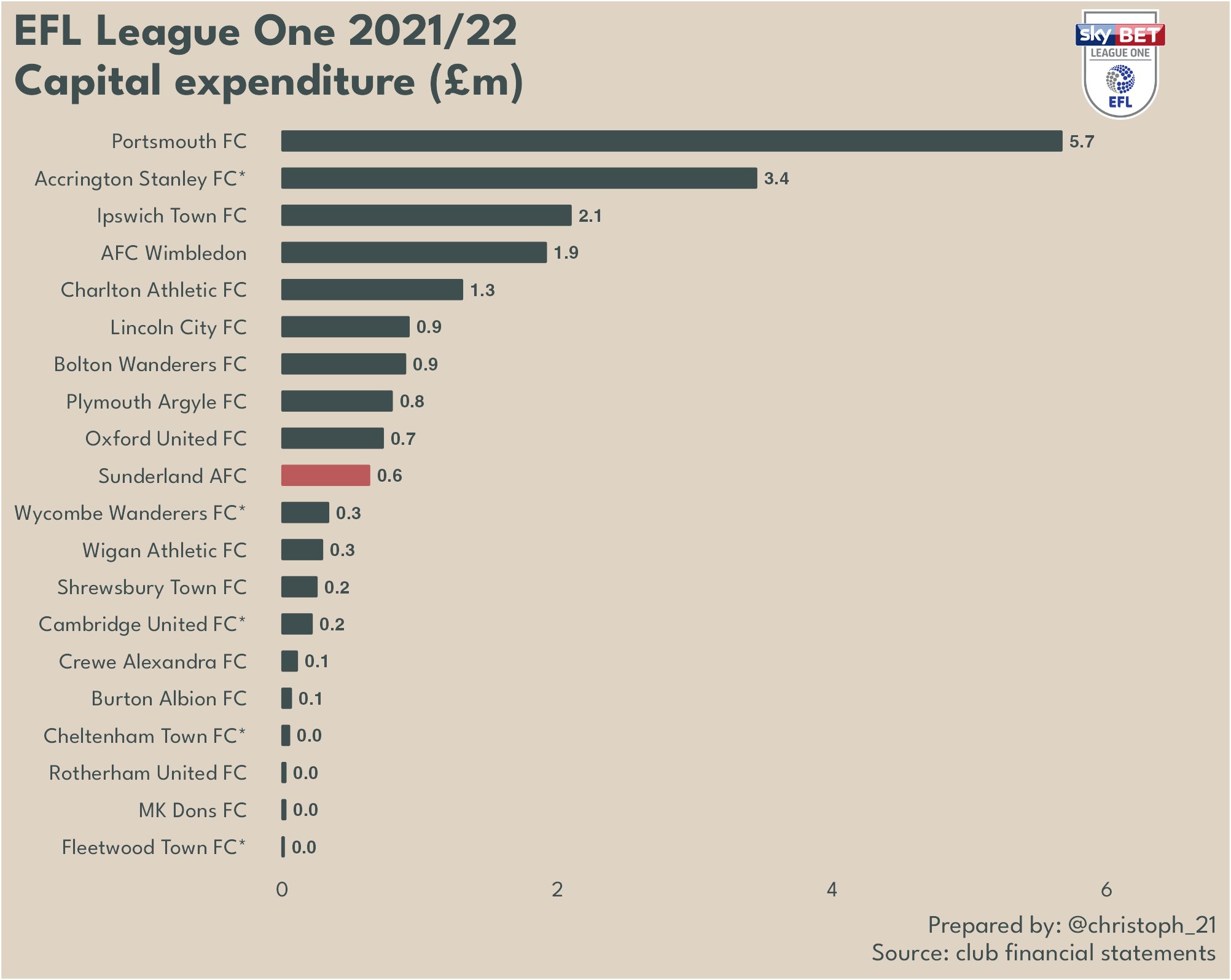

Off the field, £0.6m was spent on capital infrastructure, again the most since the club was in the EPL. As mentioned, the club’s stated investment figure on facilities was £1.3m, so £0.7m comprised repairs and maintenance rather than improvements and new assets.

That being said, £0.6m was still one of the lowest in League One in 2022. That is probably not a surprise to many observers given the continued shoddy state of various areas in and around the Stadium of Light. Pinning the blame for this on the current majority shareholder would be unfair, but it remains there is a lot of work to be done to reach the standards many expect.

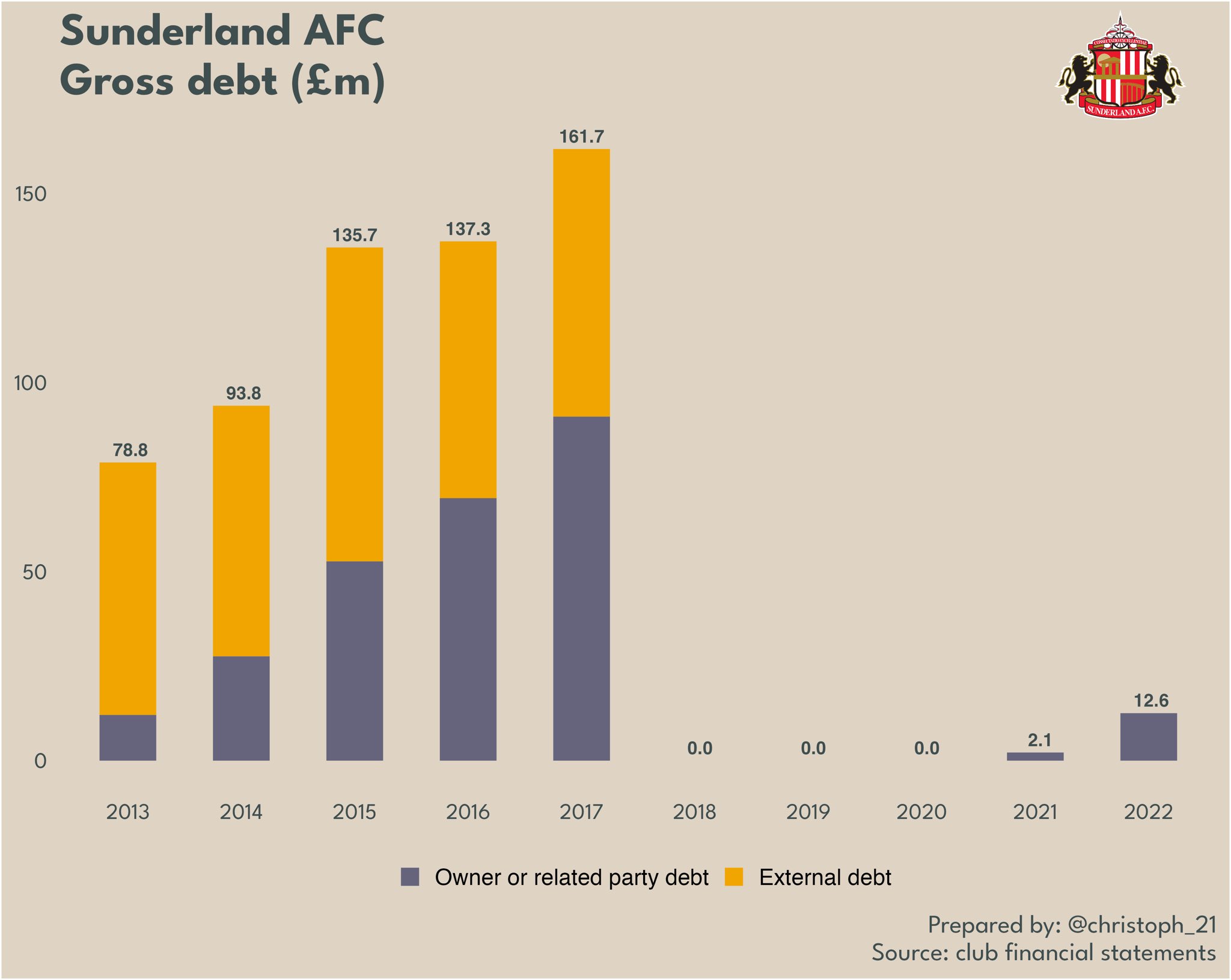

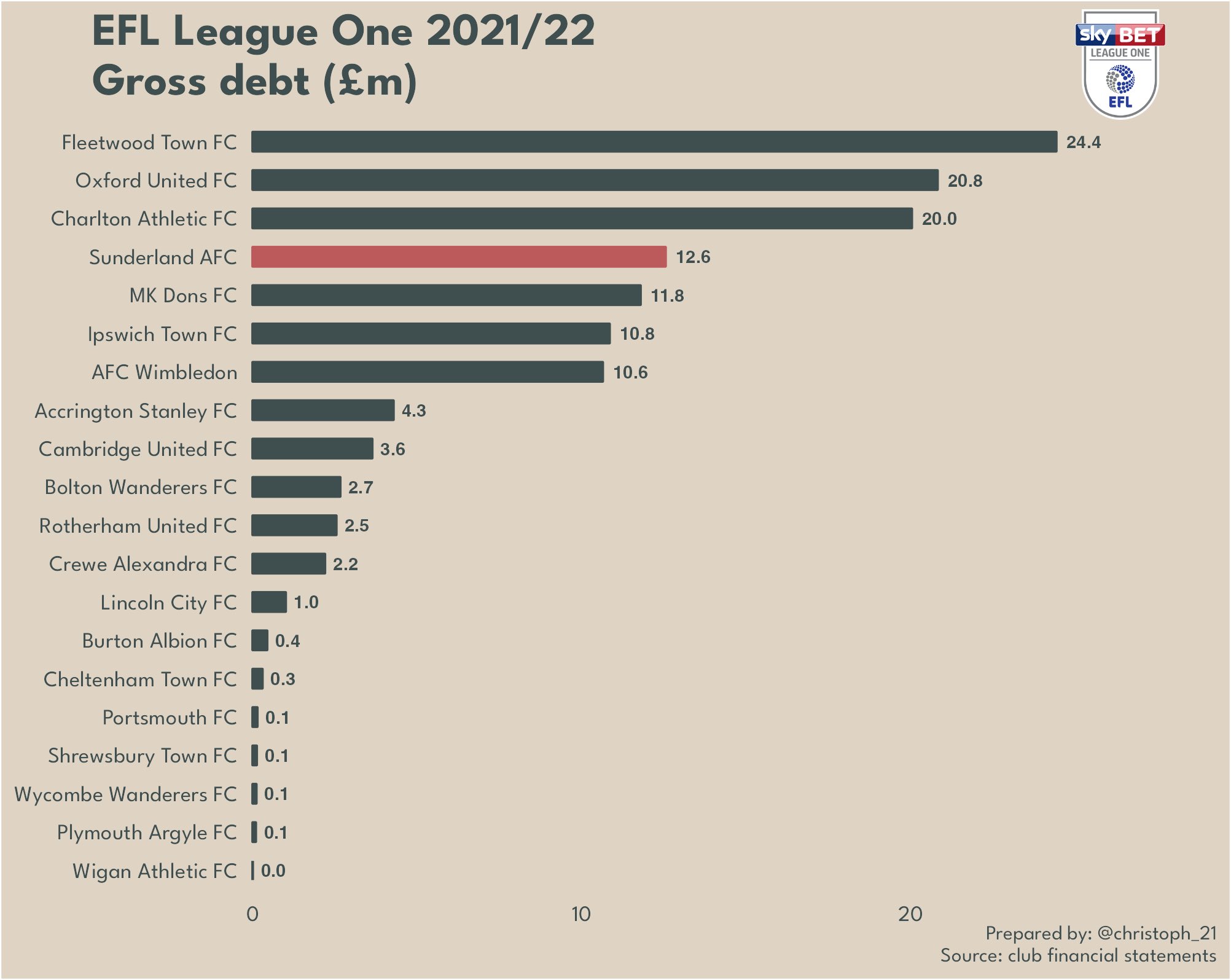

Debt

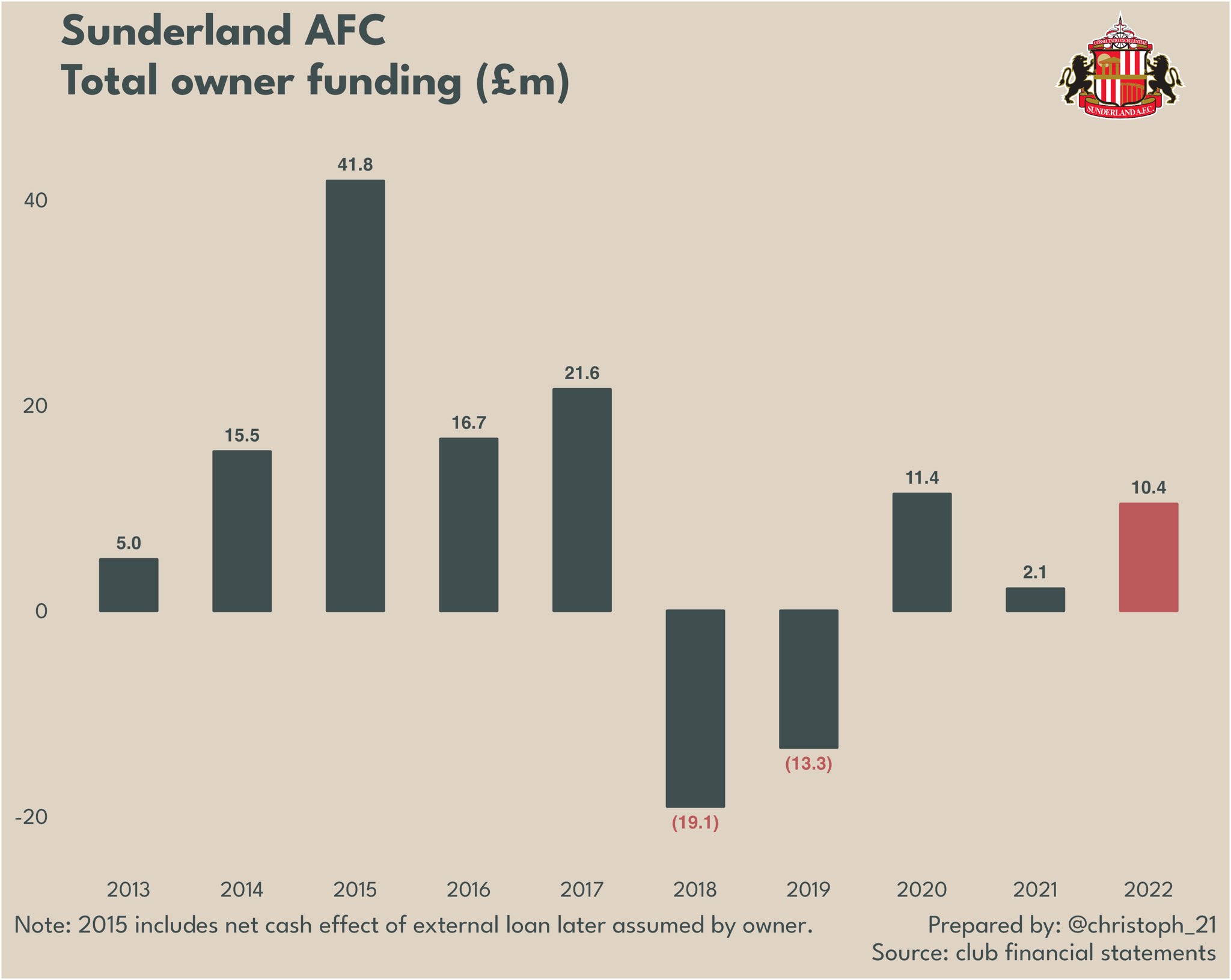

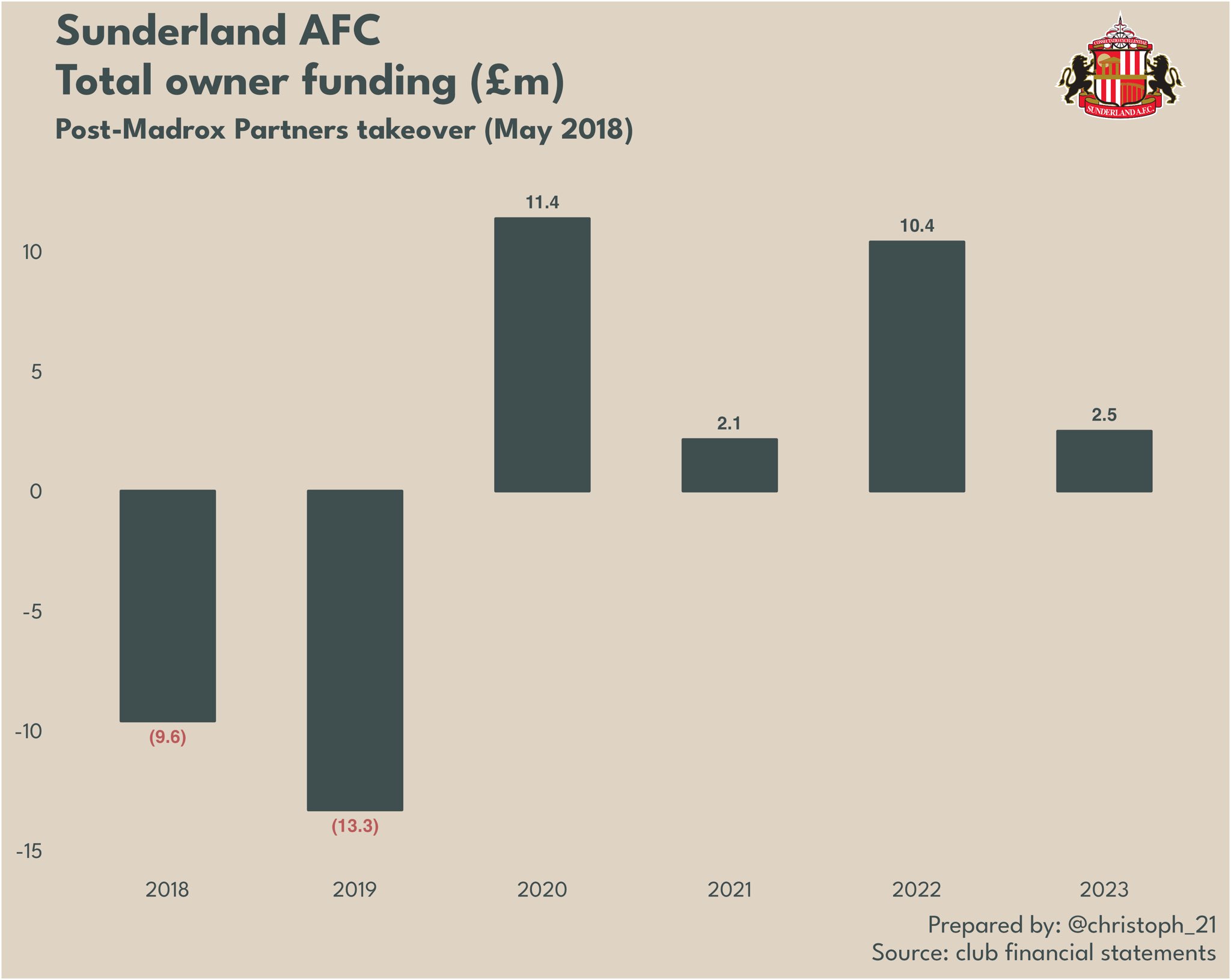

Sunderland’s debt is on the rise again, hitting £12.6m by the end of last July and up to £15.1m by 1 March 2023. However, it is all owed to the club’s owners, and no interest is charged, meaning it doesn’t impact operations like external debt has done in the last decade. The current ownership group injected £10.4m in loans in 2021/22.

One important point to note here is that the debt incurred has not yet been converted to shares. The football club accounts for 2021 stated amounts owed to shareholders would be ‘converted to equity in due course’, something which, a year down the line, has yet to happen.

The Sunderland Limited accounts for 2022 have no such statement, but nor did the 2021 report for that company; it will be worth keeping an eye on the football club accounts to see if it remains there when they are published later this week.

There is nothing to suggest the debt won’t be converted to equity as promised – no timeline has ever been set – but given Sunderland’s recent experience with owners promising things that never transpire, there’s little harm in remaining vigilant.

Sunderland’s gross debt was the fourth-highest in League One, but it is worth noting £4.1m of that debt was added between late April and the end of July 2022 – i.e. to fund building for the Championship.

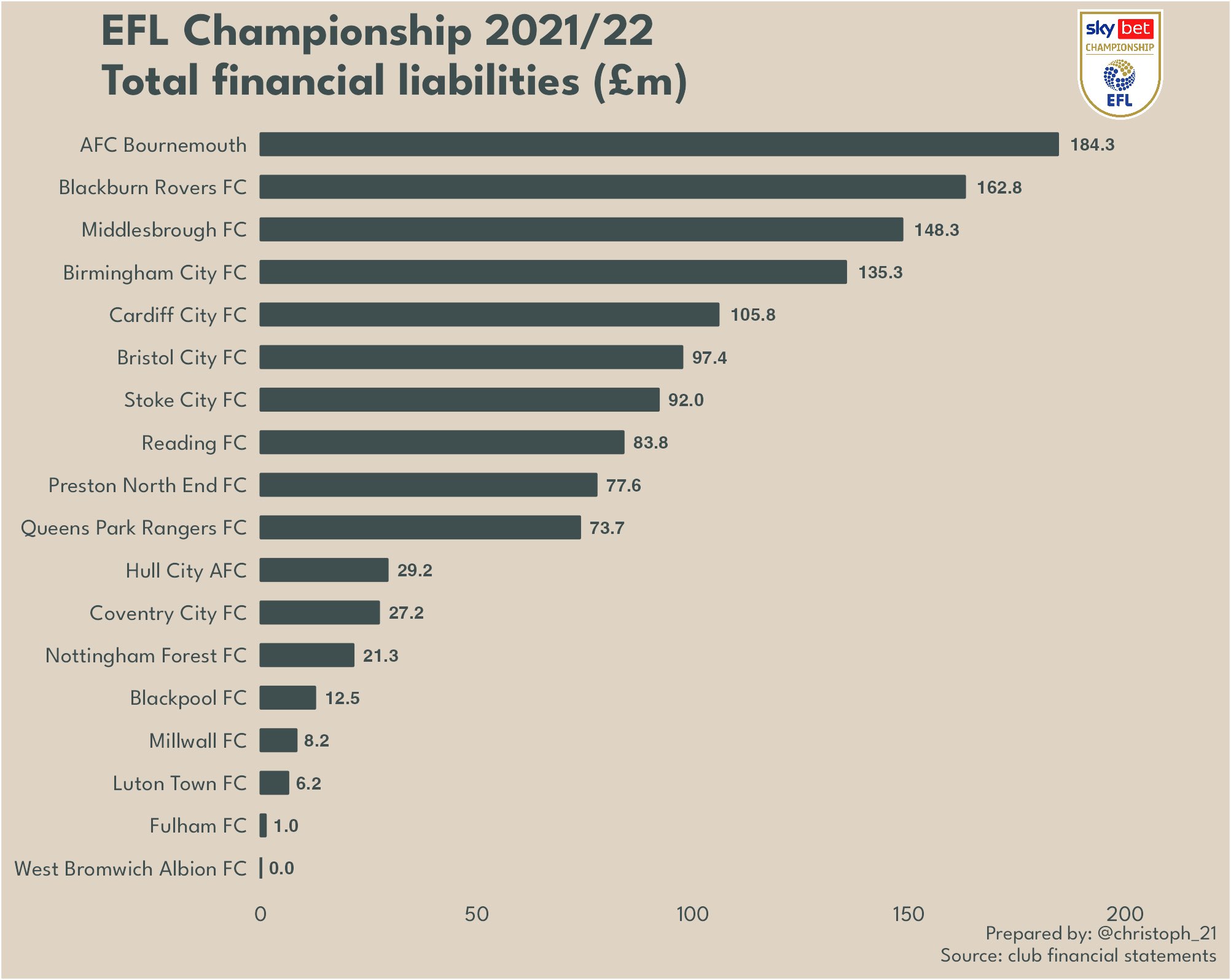

The debt levels of Championship clubs beyond summer 2022 are unknown but it’s fairly clear that the £15.1m currently owed by Sunderland to its owners is very much on the low side relative to others. Several Championship clubs are in high eight- and nine-figure debt, mostly to their owners, as years of failing to achieve promotion take their toll.

Since Kyril Louis-Dreyfus acquired his shareholding in the club in February 2021, disclosures from the accounts allow us to split out owner injections as follows:

- 19 February 2021 to 31 July 2021: £2.2m

- 1 August 2021 to 26 April 2022: £6.3m

- 27 April 2022 to 31 July 2022: £4.1m

- 1 August 2022 to 1 March 2023: £2.5m

While club cash flows are especially squeezed between March and May – minimal ticket revenues and little in the way of central TV distributions either – the fact only £2.5m has been required from the club’s owners in the first seven months of the current financial year is indicative of the club’s ongoing financial performance (and, as some will no doubt note, the lack of spending on transfers in January).

Cashflow

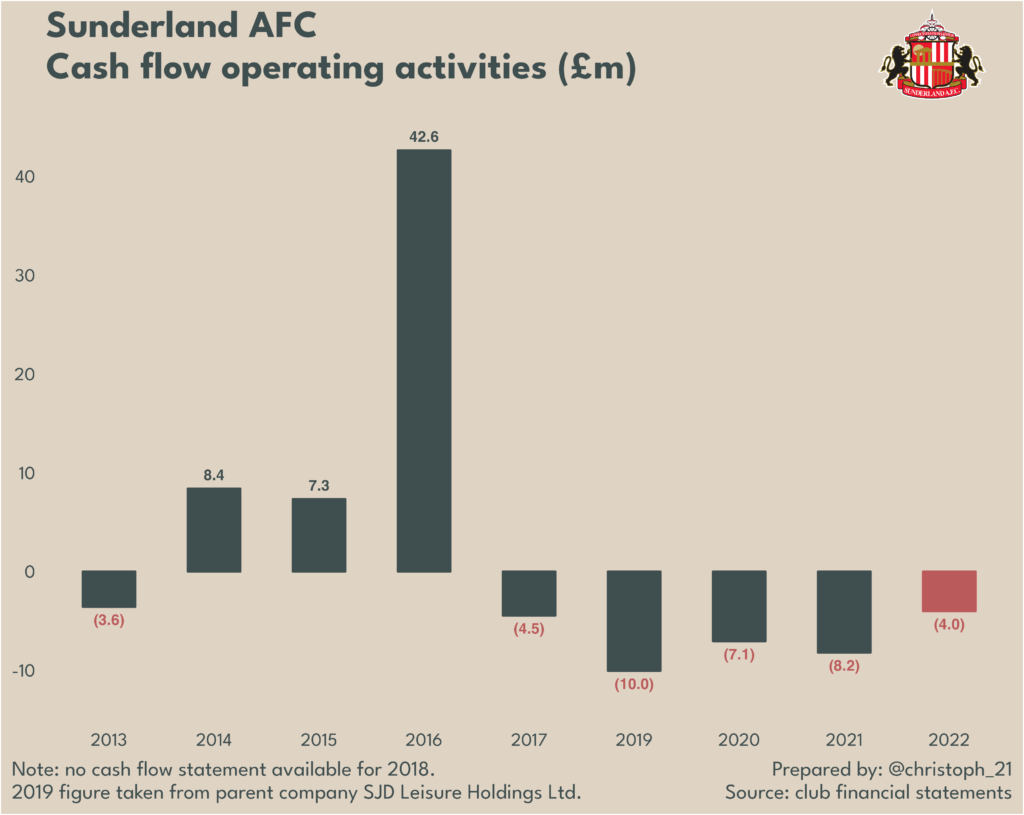

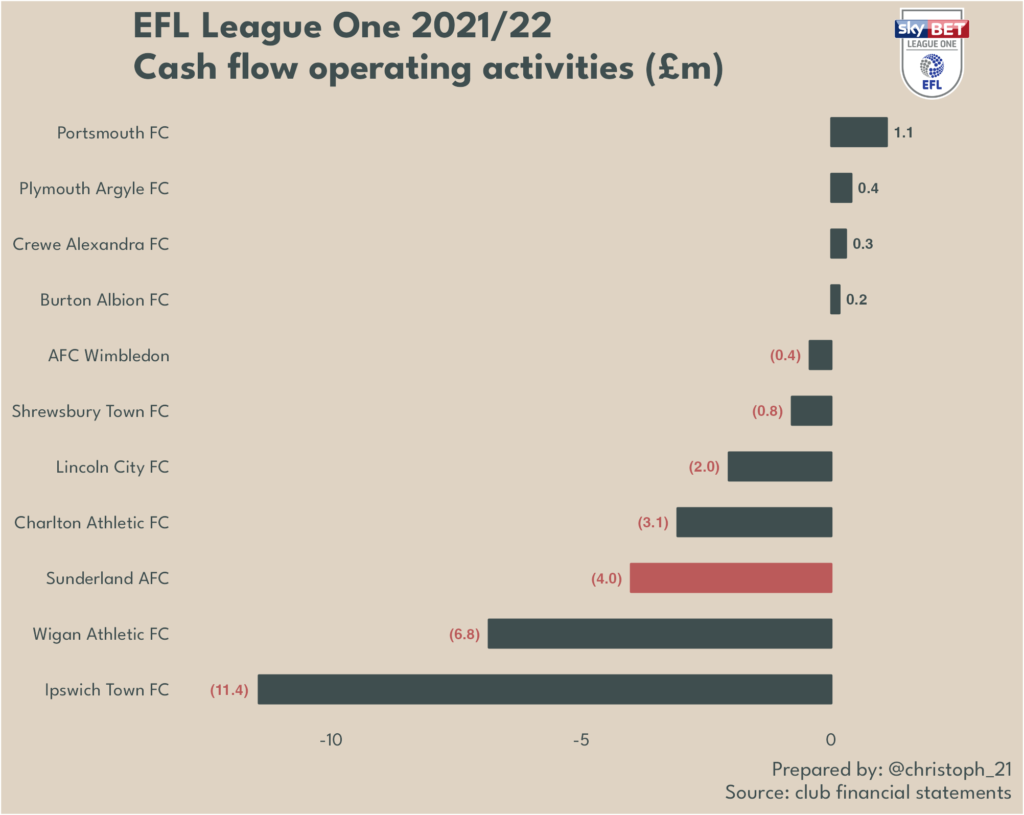

Sunderland’s cash flow from operating activities – in essence, the net flow of cash from day-to-day operations – was negative in the year, dipping £4m into the red. It was at least the fourth consecutive year that was the case for the club (no useful cash flow statement was published in 2018 due to the timing of the club being sold that year), underlining the troubles Sunderland have had generating cash outside the EPL.

That £4m figure was the third-worst of the 11 League One clubs who published a cash flow statement this year, only ‘surpassed’ by Wigan Athletic and Ipswich Town, both of whom splurged heavily on their playing squads. In a way, Sunderland’s performance here wasn’t all that bad; the club losing money on the day-to-day in the third tier is a given, and the level of lost cash was lower than previously.

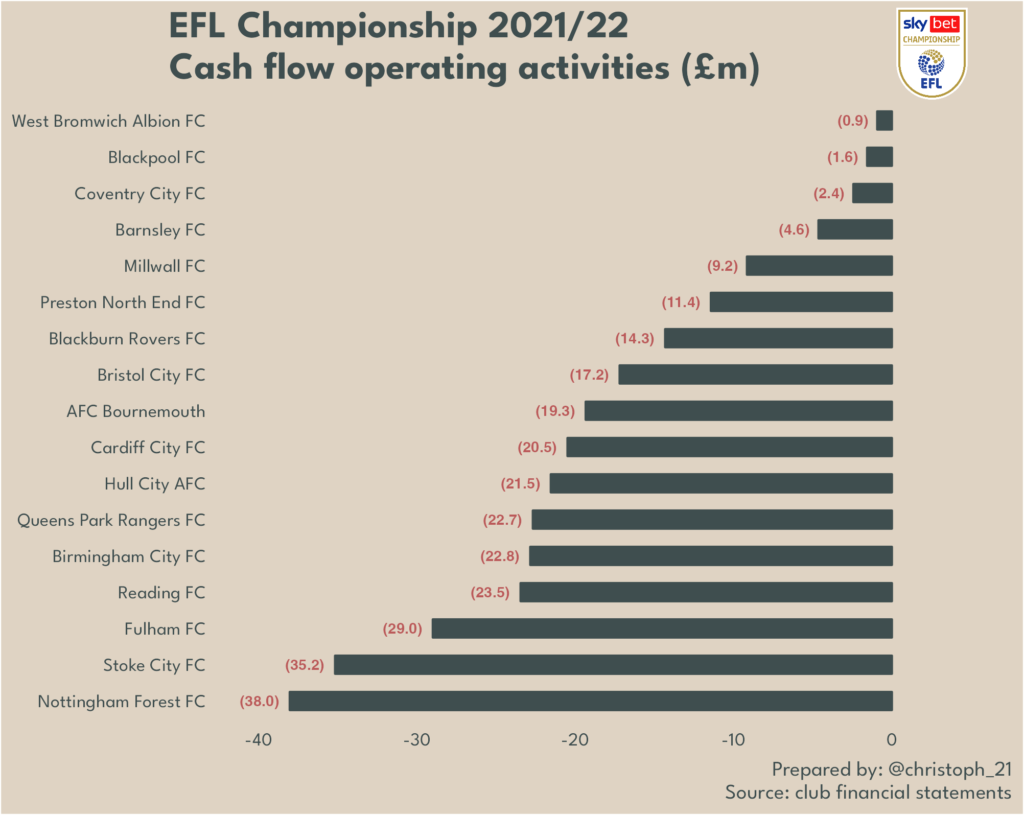

It’s obviously not all that sensible to make direct comparisons with Championship clubs, as the playing field is different, but Sunderland’s £4m cash operating loss would have been the fourth-best in the second tier last season. Much of this stems from the big wage bills in that division, and its telling that not a single Championship club in 2021/22 made a cash operating profit.

Of course, losing cash from the day-to-day means the club is reliant on money from elsewhere in order to fund its operations. With the strategy of selling players at a profit still in its infancy in 2022, that funding came from the club’s owners, whose contributions (£10.4m in loans) effectively covered both the operating loss and the club’s transfer spending.

Financial Fair Play

Financial Fair Play (FFP) hasn’t been something Sunderland have needed to be too concerned with in recent years, with League One’s more lenient restrictions on spending never really coming into question due to the club’s sizeable income and the allowances afforded during the pandemic.

2022 was little different in that regard. League One clubs are restricted to spending 60% of ‘turnover’ (quoted because the turnover allowable for these purposes is wider in scope than the traditional meaning of the word) on player wages. Sunderland’s total staff costs came in at 62% of income, meaning the club was comfortably within the 60% limit on player wages – and especially so when the playing squad’s wage bill was only £9m, as detailed earlier.

In the current season, Sunderland are subject to the FFP rules employed in the Championship, meaning the club cannot lose more than £15m over a three-year period, or £39m if club owners inject money as equity contributions rather than loans.

Given the club’s pre-tax losses in 2021 and 2022 total £15.5m, this might seem to put them close to the limit, unless the owners were to convert their current outstanding loans to shares (which, as we’ve covered, they have previously committed to doing).

However that £15.5m loss doesn’t take into account the fact the EFL effectively extended the monitoring period to four years as a reaction to the Covid-19 pandemic, allowing clubs to average their figures across the 2019/20 and 2020/21 seasons. Nor does it take into account various allowances clubs can put into their FFP calculations.

Sunderland’s pre-tax loss across the first two ‘seasons’ of the current monitoring period was £11.4m, being an average of £5.4m from 2019-21, plus 2021/22’s £6.0m. In terms of allowances, the costs of running a Category 1 academy, estimated at £5m per year, are excluded from losses, meaning the club can add back £15m across the monitoring period. Depreciation on fixed assets is excluded too, and totals around £2m.

The club can exclude community costs (est. £1m per year) and the costs of running Sunderland AFC Ladies (est. £1m over the monitoring period). On top of that, the EFL also allows clubs to make deductions for Covid-19 related losses, up to a maximum of £5m across 2019-21 and £2.5m in 2021/22.

Even without the ownership converting up to £24m in allowable cash injections into shares, the above would give Sunderland scope to make losses of an estimated £32m in 2022/23 without breaching FFP. Given the ownership has only had to inject £2.5m between last July and the beginning of March, it’s a safe bet that there are no looming issues in terms of compliance with EFL profitability and sustainability rules.

Ownership

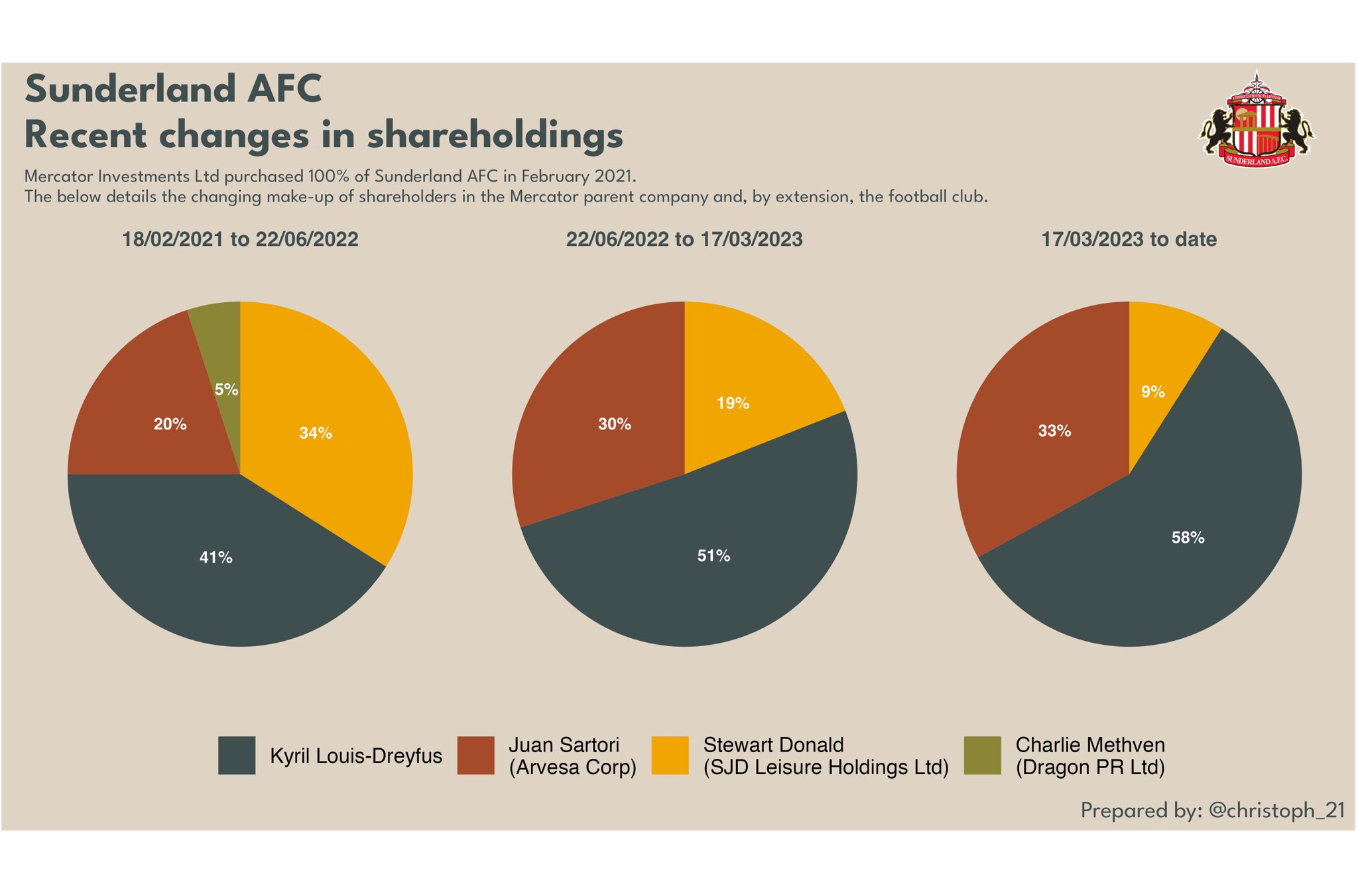

As is customary on Wearside now, there was more flux in the boardroom. After the revelation in February 2022 that Kyril Louis-Dreyfus only owned 41% of Sunderland, he moved in June to add 10% to that.

Disclosures in the accounts flesh out that transaction further, detailing that Louis-Dreyfus’s purchase of 10% came solely from Stewart Donald’s holding, with Juan Sartori obtaining 5% from Donald and 5% from Charlie Methven, whose association with the club mercifully came to an end as a result.

That transaction was followed by a further sale of Stewart Donald’s shares in March 2023, with Louis-Dreyfus acquiring a further 7% and Sartori a further 3%. That reduced Donald to a 9% holding, something which enabled him to return to Eastleigh FC and re-acquire a controlling stake there – a deal which is currently subject to approval.

Whatever the specificity of that matter matter, even after amounts taken out of the club in 2018 and 2019, total owner funding in cash terms in the last decade sits at £92m.

As a note, that figure includes the net effect of external loans taken out by the club in 2015 but later assumed by Ellis Short as part of the deal to sell the club in May 2018.

Additionally, the figure of £19.1m taken out of the club in the 2018 financial year includes not just £9.6m used by Madrox Partners to fund their purchase of the club, but a further £9.5m that was seemingly used by the club to repay Ellis Short some of the monies due to him at that time (the club didn’t produce a cash flow statement that year, so these amounts are difficult to easily discern).

Since the club was taken over by Madrox in May 2018, Sunderland AFC has received net £3.6m in owner funding. In effect, the parachute payments taken from the club have been repaid, though primarily by dent of Kyril Louis-Dreyfus arriving on Wearside The £11.4m funding in 2020 included £9m from FPP Sunderland Limited, a figure believed only to have been repaid by Stewart Donald out of the proceeds of his first share sale to Louis-Dreyfus in early 2021.

The below only shows a selection of clubs that have inhabited League One at the same time as Sunderland, owing to limitations on available data. Even so, it should be indicative of how little cash was presented to the club by its owners for much of its time in League One, and lay bare why a policy of asset-stripping was undertaken to keep the club operating.

Only since Louis-Dreyfus’ arrival has the club come to funded beyond the bare minimum by its ownership group again – and even now, the net figure received since May 2018 is well behind many other clubs.

Conclusions

All in all, Sunderland’s 2021/22 financials are more positive than fans of the club are used to seeing. Losses continued to be booked, but this was always going to be the case while the club found itself in the third tier.

Reducing those losses was an obvious positive, as were the club’s rebounding revenues – though it seems clear this owed to a mix of post-Covid enthusiasm and momentum built from the new strategy undertaken on the footballing side of the business. Future challenges will come if, or when, the latter begins to wane.

The results are by no means perfect, but then few in English football can boast good financials. Of the 77 clubs to have now published 2021/22 results, after excluding loan write-offs from benevolent owners, only 18 booked a profit. Of those 18, just seven managed a profit in excess of £1m – and five of those clubs were in the EPL.

Sunderland are not operating at the best they can do yet, but strong steps have been made in the right direction. The club’s revenues have rebounded post-Covid, and commercial income has increased impressively, especially given the fairly unimpressive offering most fans have witnessed.

Most importantly, savvy recruitment has built a squad that has not only survived in the Championship but emerged as genuine play-off challengers. The next stage of the club’s recruitment strategy and the coming summer looks crucial, but it is hard to argue the early shoots have been anything other than a success.

Much of the above, though not all, was detailed in a lengthy Twitter thread on Saturday morning. You can find it here.