The downside of football clubs not having to release their financial statements until nine months after the fact is fairly obvious: a lot can happen in nine months in football. The upside, in Sunderland’s case, is that a lot very much has happened since the end of July 2020.

Now that Kyril Louis-Dreyfus has arrived on scene and, we believe, ensured the financial safety of the club for at least the next couple of years, it might seem easy to dismiss the club’s 2019/20 accounts as irrelevant. After all, the situation the club finds itself in now and moving forward is very different from then.

That is mercifully true and yet it seems a tad negligent to completely ignore such things. Last season was, statistically and otherwise, the worst in our history, so it would be a bit remiss not to try and understand how off-field activities drove that. That’s before even mentioning that not writing this piece would serve as something of a dereliction of duty in my profession as a full-time boring bastard.

Another loss – but a much lower one

At first glance, one might be forgiven for thinking the tale of Madrox in charge of Sunderland in 2019/20 was a job well done. After all, the club’s consolidated loss before tax – i.e. after we strip out the nominal £2m rent the football club ‘pays’ Sunderland Limited for use of the Stadium of Light – was just £1.3m, the lowest since 2007.

The club has posted a loss in each of the last fourteen seasons, combining for a total of £242m. Which, if you weren’t already sure, is a canny bit. In that context bringing losses down to a mere £1.3m should seem commendable – particularly in a year where four and a half months were ravaged by a worldwide pandemic.

At the time of writing – daft o’clock in the evening, if you must know – only eight other League One clubs have published accounts with sufficient detail for the 2019/20 season. Almost all made a loss: AFC Wimbledon benefited from £13m of s.106 income to help build a new Plough Lane, and would have recorded a loss otherwise; Oxford United benefited from some bumper sales to loftier clubs; Portsmouth sneaked into the black.

Truthfully, given the onset of the pandemic last March, clubs posting a loss shouldn’t be too surprising.

And certainly, in a year like 2020 and one where, as we’ll discuss, Sunderland’s income fell substantially, posting a loss 85% lower than a year ago doesn’t look too shabby. Yet as with everything since Madrox darkened our door, the reality is a little harder to unpick. In truth, the £1.3m loss of 2019/20 would look considerably less impressive were it set alongside a profit in 2018/19 of £12m – which is precisely what the club would have posted had its owners not written off £20.5m a year ago.

We’ll return to that £20.5m soon enough (it’s me, did you really expect I’d let it go that easily?), but in the meantime let us consider the more normal aspects of the club’s operations.

Parachute coming in to land

Last season marked the final year we enjoy the benefit of EPL parachute payments and, correspondingly, those fell from £34.2m in 2018/19 to just £15.2m. As a result, Sunderland’s income quite literally halved, down to £29.2m, the smallest amount of revenue the club has enjoyed since Roy Keane’s promotion season.

Having said that, such is the size of those parachute payments, Sunderland’s income still dwarfed that of our fellow League Oners. Pompey’s £11.2m is actually a fair way ahead of most other sides in the division, yet looks minuscule when set alongside Sunderland’s income. Indeed, even without parachute income, Sunderland would likely have been the league’s highest earners, with the possible exception of recently relegated Ipswich Town.

Regardless, income fell across the board on Wearside. Gate receipts dropped to £5.7m, our lowest figure since the 1990s, reflecting not only the loss of three home games to the pandemic but also the club’s average attendance falling from 32,157 to 30,169. Perplexingly, Phil Parkinson’s brand of football didn’t get punters bursting through the turnstiles.

What is more, while ticket sales fell and the club was required to refund season card holders for those lost games, the income the club garnered from those it did manage to get into the ground dropped too.

Both last season’s figures and the year before’s are skewed somewhat by the appearance of £3 tickets for EFL Trophy games, but garnering just £9.50 per head per game tells its own story. It will doubtless be a metric Louis-Dreyfus and his new management team are keen to improve swiftly, as evidenced by the recent hike in season card prices.

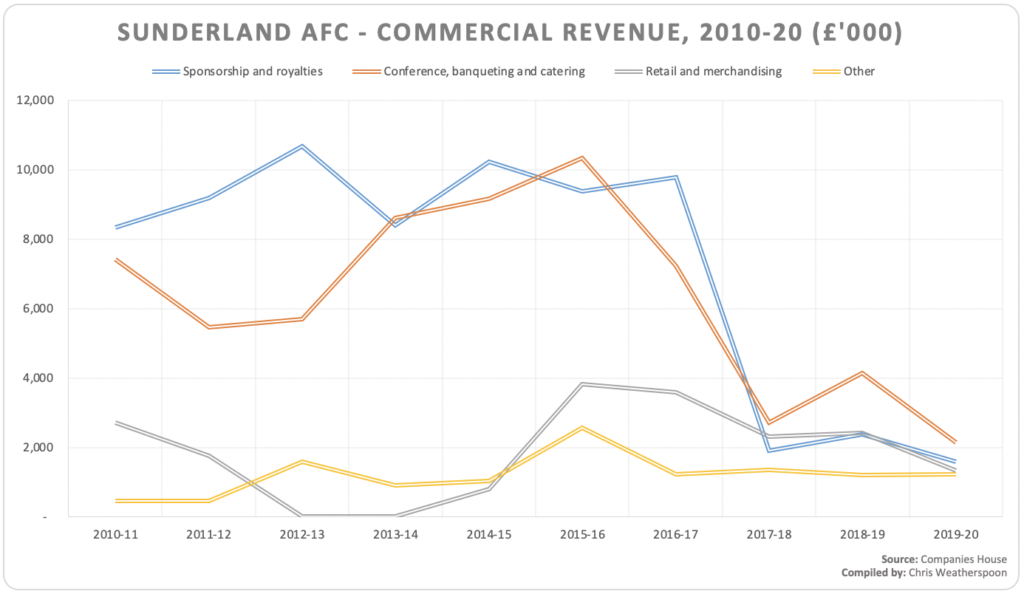

Away from gate receipts, the club’s commercial income also took a dive. Again, the pandemic won’t have helped matters here, though its questionable how much the club would usually recoup from the likes of retail at the end of the season.

Giving credit where its due, Madrox did a pretty good job of improving commercial income in their first season at the helm, lifting it from £8.3m to £10.1m. Yet that improvement was wiped out and then some last term, as commercial income fell to £6.3m.

That’s reflective of the pandemic, but a few other things too. For one, the novelty of League One had well and truly worn off; for another, the shearing of staff from the club – a further 21 full-time staff, or 10% of the total at the end of 2018/19, were removed from the payroll last year – diminished its ability to run the effective marketing campaigns that had been something of a hallmark in our first season down here.

Cost-cutting our way to, well, nowhere

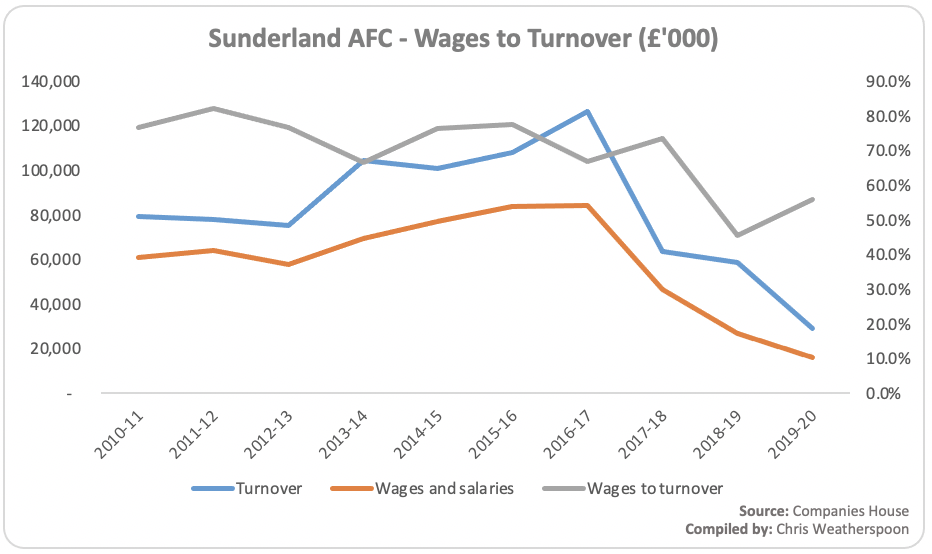

As revenue fell so would costs need to and so, unsurprisingly, they did. The club’s wage bill dropped by another 39%, now coming in at £16.3m, as low as it was back in the 2004/05 Championship season. From a high of £84.4m under David Moyes, that’s a fall of 81% in just four years.

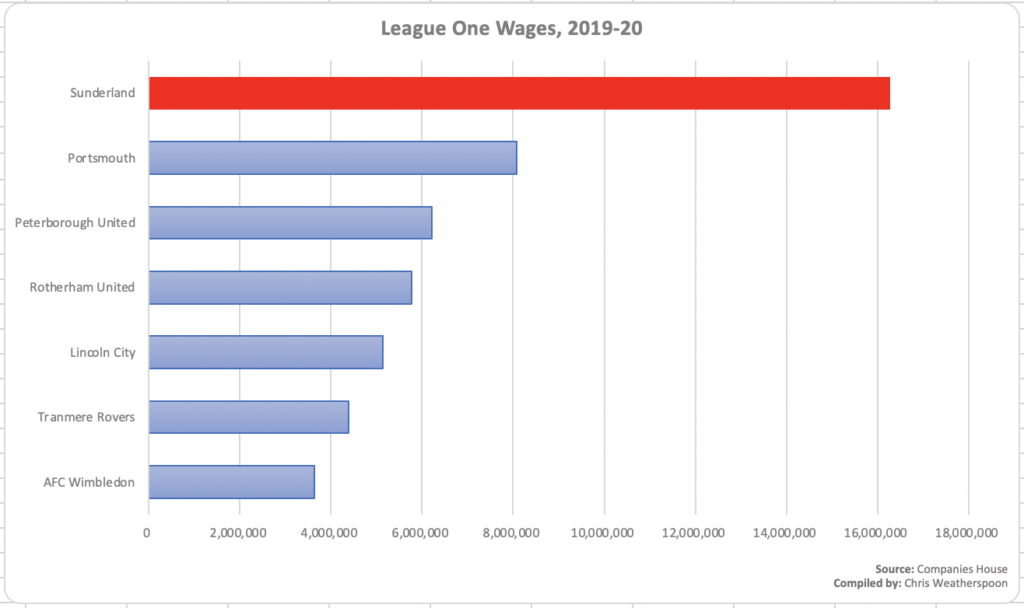

That’s pretty impressive from a numbers perspective. Unfortunately, from a footballing point of view, performances might well be 81% worse than then too. The club’s wage bill needed trimming upon tumbling into this league, yet it’s telling that even now it far outstrips those clubs we’re competing against.

The club rid itself of some high earners, yet the fact that we agreed contract deferrals with the likes of Lee Cattermole and Bryan Oviedo meant their wages were still overhanging, and likely still are this season too. Given there were relatively few pre-Madrox players left on the books last season, its astonishing that we managed to spend quite so much on a squad that wasn’t even close to topping the only table that counts.

Set alongside accounts published for last season, Portsmouth’s £8.1m is half ours. They finished fifth, us eighth. More gallingly, Rotherham United, promoted automatically, expended just £5.8m on wages. Coventry City spent £5.3m in 2018/19, a figure that is unlikely to have ballooned during their promotion season last year.

Wycombe Wanderers, the third team to vault into the Championship, don’t release wage data. Not because they don’t like to, rather because they’re too small a business to have to. Which should be pretty telling about how big their own wage bill is.

There’s a widely held maxim in football finance that the league table generally correlates with how much clubs spend on staff costs. During the ceaseless relegation battle that was our stint in the Premier League, Sunderland largely bucked that trend by finishing lower than we should have. It brings me absolutely no pleasure to report that we’ve remained thoroughly consistent in that regard.

Elsewhere in the costs category, the club managed to make yet more cuts to its day-to-day cost base.

Other expenses, which is, generally speaking, a lot of fixed costs and all the things that make a business a business, fell a further £3.5m (28%) to £8.9m. Back in the Premier League these costs sat at around £23m, which, like the wage bill, means there’s been a pretty hefty fall.

We’ve all heard the tales of expensive plant pots and cryochambers going unused, so in one respect it’s commendable that Madrox have managed to take such a sledgehammer to the club’s cost base. Yet the cutting is the easy part. Cutting and building something in its stead is far harder, and they’ve summarily failed in that regard.

Truthfully, it’s a surprise that other expenses fell this far again; the likelihood is the pandemic shutting down operations for over four months helped the club, quite literally, keep the lights turned off.

One financial metric you may have heard of before, but not necessarily understood or cared about, is EBITDA. Without boring you (any further) with the details, it’s essentially a club’s cash operating profit, not including any player sales or exceptional items.

Sunderland’s EBITDA in 2019/20 was positive at £2.3m. Yet it fell substantially from 2018/19. Or at least from what it should have been that season; the £17.3m EBITDA figure for that term is inclusive of the £20.5m that was effectively stripped out of the club’s income.

Positive EBITDA may initially bode well for the future but it shouldn’t be forgotten that this included £15.2m of parachute income. Without that the metric would have been firmly in the red. Combine that with a pandemic-induced empty stadium and it’s not hard to reason that finances might have got a tad tight in our current season. Certainly, Mr Louis-Dreyfus won’t be expecting a return on investment any time soon.

Investment, or lack thereof

Away from the income statement, the club spent a paltry £199k on new players in 2019/20. Pretty much the entirety of that is believed to have been expended on prizing George Dobson from relegated Walsall, a move which I’m sure you’ll agree was worth every penny.

Five of the eight clubs to declare results to date outspent us on fees, which needn’t necessarily be an issue in its own right. After all, we spent £3m on Grigg and got Jordan Willis for nothing, and it doesn’t take a genius to decide which one worked out better.

Yet that slim spend on the playing squad is indicative of a lack of investment across the board. Having gone wild on Grigg months earlier, the taps were effectively turned off. That scene in Sunderland ‘Til I Die season two, where Donald questions whether he has the money to run the club for a second season in League One, wasn’t exactly an act.

For the third season running, the club received more in transfer fees than it expended. In total the club recouped £3.4m on player sales. That might be deemed a success for most clubs in this division, but we aren’t most clubs and, again, some context is required.

The exact fees on sales aren’t known but, generally speaking, the bulk of that income was derived from selling off academy prospects. Joe Hugill, Logan Pye and Bali Mumba were the most high-profile, and should have topped at least £1m in fees between them. George Honeyman went to Hull City in exchange for around £400k, which might seem alright until you consider we sold Jack Ross’ captain, with Honeyman seemingly ambivalent at best, a mere couple of days before the new season started.

Oxford United eclipsed us in the player sales profit stakes, but while they were selling first-teamers for solid fees, we appear to have been flogging our future to keep the lights on. A look through our departures between 1 August 2019 and 31 July 2020 show few public fees of note and plenty of youths exiting the building, and it’s not exactly hard to understand why.

Our transfer activity did mean that for only the third time in a decade we stood in a net positive position in terms of fees. At the end of July we owed nobody a jot and were due £1.6m from club(s) unknown. That is, clearly, a positive, but does also bear the hallmarks of an ownership group who spent much of their time here readying us for a sale.

Nowhere was that more evident then in the complete lack of investment in the club’s infrastructure. Sure, Sir Bob Murray did the hard work on that front, but there’s a general level of upkeep required to keep things looking nice.

After all, when Madrox accepted that $12m loan from FPP Sunderland way back in November 2019, Charlie Methven claimed it would be spent on capital items such as an Academy of Light lift and a new speaker system at the stadium.

I’m sure, then, you can imagine exactly how absolutely un-fucking shocked I was to peruse the accounts yesterday and find that, of the £9m set aside to turn the Stadium of Light into Ibiza’s Ushuaia, the club had spent just £16k. Yes, a club of our size spent just sixteen thousand British pounds on Capex in 2019/20. That’s not just lower than all of those eight other clubs to release last year’s accounts, but it would also wind up near the bottom of the year before too.

We will return to that FPP loan soon enough but for now it should be enough to say that, far from Charlie Methven having a day off and saying something that turned out to be accurate, that money was never likely intended to be used by Madrox to improve the club’s facilities. All evidence now in the public domain instead points to it being used as lifeline up until they point they could find someone to sell to.

One thing Madrox have been keen to play up at absolutely every turn is the fact the football club is debt-free. That they had absolutely sod all to do with that being the case (Short was, whatever they may have said, going to have to write off huge amounts whomever he sold to), appears not to matter a jot.

Debt in League One isn’t quite as prominent as it is just one division above, and even less so now Ipswich have been bought out, and those clubs that are indebted largely owe the money to their owners. Even so, were it not for the Alvarez court case loss incurring £960k of interest, Sunderland’s debt and finance costs in 2019/20 would have each been nil.

This is what good looks like

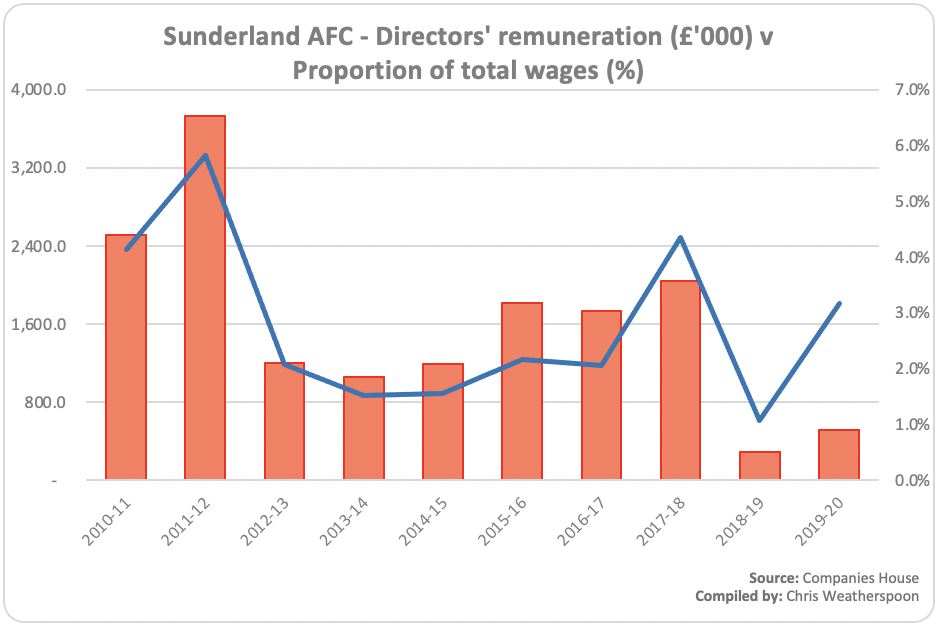

Moving into the boardroom, last season was fairly tumultuous. Tony Davision stepped down from his Managing Director role in the autumn of 2019, Methven, at least officially, followed suit in December in a move that absolutely wasn’t linked to comments he made at a meeting with fan groups, and Donald himself departed from the chairmanship just before the financial yearend, in a move that was more symbolic than meaningful.

Betwixt that, Dave Jones and Tom Sloanes joined the board as non-execs and Jim Rodwell arrived as CEO. The latter were believed to be unpaid; the former less so.

Whatever the makeup of payments, collectively, club directors enjoyed an 81% pay bump. £516k pales in comparison to the frankly ridiculous sums we were shelling out to people overseeing the slowly rotting carcass of a Premier League club we once were, yet for pay at the highest levels to leap up in a time when the club was clearly teetering financially leaves a sour taste. When we consider Rodwell was hired after the commencement of the pandemic and the accompanying financial chaos, well, I’ll not say any more for fear of another legal threat.

In total, director pay comprised 3.2% of the club’s total wage bill, which is higher than six of the last ten years. Among that £516k was £132k for loss of office, a sum believed to be, but not confirmed, and I apologise if there’s been crossed wires here, paid out to the departing Davison.

Elsewhere, a company controlled by Stewart Donald invoiced the club for £119k. What exactly that relates to is unknown. My original bet was it’s probably for the services of Neil Fox, Mr Donald’s consigliere, if you will. Millwood Enterprises, where Fox shares a directorship with Donald, billed the club £200k in 2018/19. Yet a closer reading of the above suggests any payment relating to Fox would be wrapped up in this year’s £312k figure.

If that’s the case, £119k seems to have been invoiced by one of Donald’s other companies, for services unknown. It’s fairly small beer for Donald to be paying himself, especially when there’s £20.5m you can apparently write off with minimal shame, but given that this expenditure has appeared in a year like last, I guess you can’t rule anything out. Whatever it related to, I’m sure when pulled on it Madrox will advise it’s a perfectly legitimate business expense.

Separately, going back to that £312k, per the above tweet, Methven snaffled £120k of the £320k in their first year up here. It would follow, then, that the £312k is split somehow between himself and Fox – although only an £8k reduction is puzzling when Methven officially resigned just four months into the financial year.

Whether he received a golden handshake for insulting half of the North East is unknown, but strikes me as unlikely. More interesting to note is the fact he seems to have been paid previously not as a director but via his own company, so there’s no guarantee that stopped when he resigned his directorship.

Whatever the make-up of the directors’ and related party payments, we can probably all agree the club didn’t exactly get great value for money in return. Taken altogether, the amounts dispensed to directors and related parties total £947k. You could be forgiven for thinking the club was in any strife at all.

I want my money back

Speaking of not getting things in return, the question on many lips when these accounts dropped yesterday was a fairly simple one: just how much of the £20.5m written off last season would be returned to the club in the following year?

On this evidence, erm, none. As at 31 July 2019, Sunderland AFC was still owed around £2.4m from its owners even after that debt write-off. Roll on twelve months and that figure has plunged to £67k, by way of cash injections, primarily from Stewart Donald.

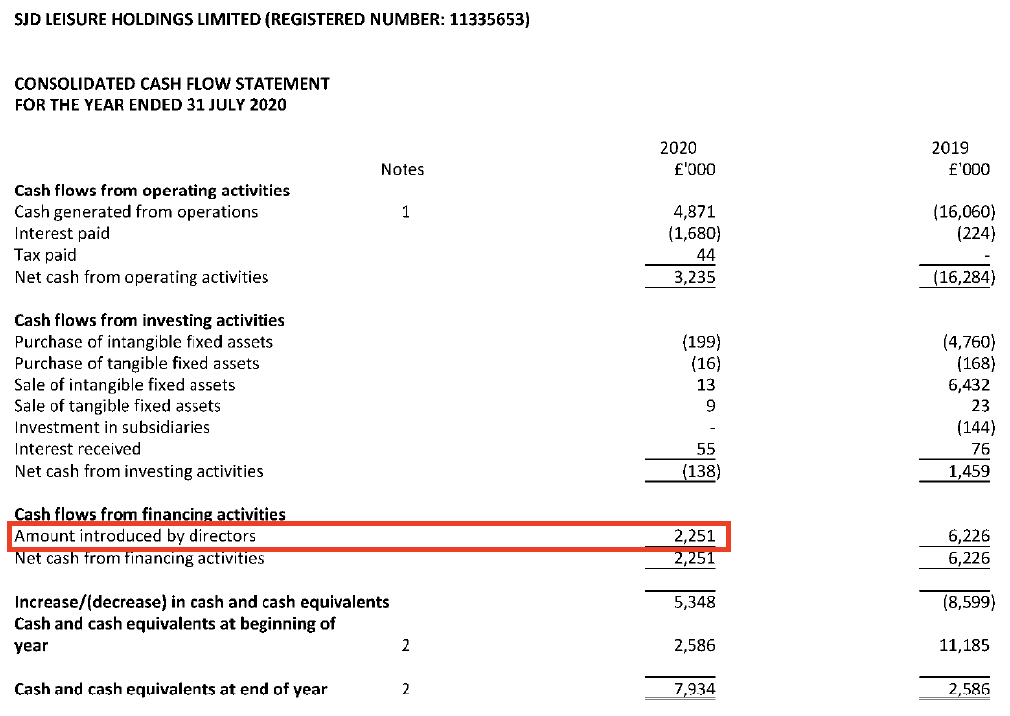

How kind of him, you might think. No? Me neither. Donald injected £2.25m through his SJD Leisure Holdings parent company in the year. That took his total financial commitment at Sunderland, to 31 July 2020, to £13.477m.

Now, call me cynical, but that’s a lot less than the £50m he claimed to have shown the EFL he had ready to spend on the club. It’s even quite a bit less than the £37m the club was eventually purchased for. And, lo and behold, it’s actually less than the £20.5m that was written off a year ago, but we were told would be paid back, returned, given to us when we’ve shown we’re responsible enough to use it. For anyone thinking otherwise, that last bit is a joke.

You might wonder why this still matters. It is, after all, fairly old ground. I spent a sizeable chunk of yesterday evening trying to pull together a graphic that would easily explain where all the cash had flowed in relation to how Madrox bought our club, just to put it to bed once and for all. Then I realised it was giving me a headache.

Unfortunately though, it does still matter. Ultimately everything that has happened at this club since May 2018 stems from Madrox buying it, and therefore stems from the patently obvious fact that they either never had the money to run the club to a standard we all expect or, rather more unlikely in my view, did have the money but had no desire to spend it. Academy kids sold, staff made redundant, three-potentially-soon-to-be-four seasons in this Godforsaken division. It all goes back to them getting their hands on us.

Madrox’s accounts are tough to follow at the best of times, with deciphering them kind of akin to watching an episode of Sherlock while pissed. Yet, I think the above just about gives us the answer to the question many have also had, that being: how much did our once-loved triumvirate actually part with during their involvement with our club?

Looking at Madrox’s accounts, it seems that in total Donald, Methven and The Invisible Juan Sartori had collectively expended £17m on Sunderland AFC to the end of last July. That would be £13.5m from Donald and £3.5m from the other two; my bets are firmly on the bulk of the latter being paid in Uruguayan Pesos.

That is, obviously, way below what they said they were paying. It’s also below what they wrote off. But more intriguing is that they appear to have made heavy use of that loan from FPP, a sum which, lest we forget, Stewart Donald once claimed they had no use for and could easily pay back.

At the end of last July the club’s cash balance sat at £7.4m. The eagle-eyed among you will notice that is less than the £9m injected into the club via FPP’s loan to Madrox. That means the loan was being used up then and, actually, the club’s cash balance will have been bolstered both by recent sales of youngsters (Mumba, Hugill and, I think, Pye, all officially left in July), as well as the first direct debit instalment for 2020/21 season cards.

A few months later in December, the Alvarez case was lost and a near £6m bomb was waiting to go off. Soon after that, Donald was reported as claiming to other chairmen that Sunderland were at risk of administration if not provided with outside financial assistance.

Rodwell rubbished such reports but the financial disclosures released yesterday suggest, actually, while Sunderland AFC might not have been close to bust – FPP would have assumed control of the club by default – its owners almost certainly were.

I am sure, if asked, Madrox would claim the £20.5m was returned subsequent to last July but prior to Louis-Dreyfus’ takeover. Take a look at their statements around the time that tale first leaked and you’ll see their uncanny knack for obfuscation as opposed to outright lying. The truth as I see it is that it is highly unlikely any of that money has since been repaid and it is, to all intents and purposes, likely never to be seen again.

What a delight it would be if we are able to say the same of Madrox. In summary, Sunderland AFC’s 2019/20 accounts tell the tale of a club being pared to the bone, both in the name of making the entity look more saleable and because, quite frankly, those in charge needed to cut and cut in order to keep the lights on.

The pandemic impacted the club, of course it did, and it is hard to quantify how much. Yet the real tale of these accounts is separate from Covid-19 – it is one where fans were misled but, ultimately, the numbers never lie.

What’s next?

Mercifully Madrox are no longer in majority control and, though they retain minority shareholdings, the hope is this is the end of trying to interpret financial chicanery at our club.

Moving forward, there was a huge job on hand before the pandemic, and an even greater one now. Already nosediving revenues will have plummeted further during a season without fans present, and it will take a while for Kyril Louis-Dreyfus to turn a profit.

Thankfully the sense is that isn’t what he’s here for, certainly not primarily. One upside of the club being down to its bare bones is that it gives a new owner a fairly clean slate to work with, and plenty of scope to mould the club as he sees fit.

If he can do that successfully, we will all be thankful, even more so given the horrors of the past couple of years. I said a couple of months ago that the aim now was to never mention Madrox again. This article, this week, counts as a fairly substantial relapse, but I think that might be the end of it.

Onwards.

Chris Weatherspoon

[Note: the section relating to payments to related parties has been edited for clarity since this article was first published.]